Living with canine lymphoma: it's possible

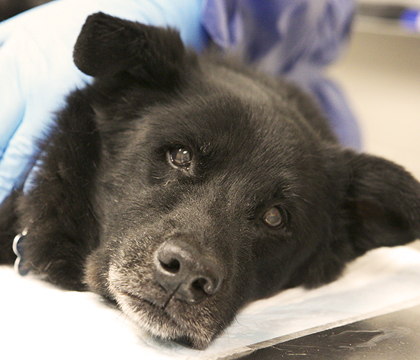

While dog owners may be shocked and dismayed to hear that their seemingly healthy pet has been diagnosed with canine lymphoma, veterinary medical oncologist Dr. Valerie MacDonald has encouraging news for them.

By Lynne Gunville"Canine lymphoma is one of the most rewarding cancers to treat because so many of the patients – 85 to 90 percent of them – respond to chemotherapy. They go into remission and do very well," says MacDonald, an associate professor at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).

"We know that we can't cure them of the disease, but we can keep it in remission for a period of time."

Canine lymphoma is a systemic disease that can arise in multiple areas of the body, all at the same time. Because the disease is most commonly seen within the lymph nodes, the initial diagnosis may take place during a routine health check when the veterinarian notices that a dog's lymph nodes are enlarged.

Although these "happy dogs with lumps" generally feel fine, they will soon become sick unless they are treated.

Because so many parts of the body are involved, chemotherapy rather than surgery is the usual form of treatment for canine lymphoma. The chemotherapy protocol involves the use of several drugs in combination, with each one killing the cancer cells in a slightly different way.

While side effects can include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and susceptibility to infections, MacDonald points out that less than two per cent of their patients develop severe side effects.

"We know that we're not going to cure them of the disease, and we do not want the treatment to be worse than the disease itself, so the doses that we use are aimed at keeping it in remission. The majority of the dogs that are in waiting in reception for their treatment are bouncing around and pretty happy. They're not sick dogs."

Sitting down with her clients and providing them with information about the disease and about treatment options is a key part of MacDonald's work as a veterinary oncologist at the WCVM's Veterinary Medical Centre.

"We have a very long consult with the owners to explain the prognosis and the percentage of dogs that will go into remission. We also let them know that, generally, while the dogs are receiving chemotherapy, their quality of life is really good. And that's always the bottom line with us – it's all about the quality of life."

While most dogs can get through the entire chemotherapy protocol, the cancer cells eventually return. And that's why the median survival time for canine lymphoma is one year with chemotherapy treatment, with 25 per cent of the dogs living for two years.

"Our biggest challenge is that the cancer cells often become resistant to the chemotherapy drugs, and once we can no longer use those drugs, our chance of getting the animal back into remission that is durable becomes substantially lower," explains MacDonald.

That challenge is one of the main reasons that MacDonald, along with Dr. Casey Gaunt from the WCVM's Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, are participating in a University of Saskatchewan study aimed at testing the effectiveness of a drug that could potentially kill drug-resistant cancer cells.

In the meantime, MacDonald hopes that educating people about the disease will help them to develop a more positive view when it comes to a diagnosis of cancer in their pets.

"I'd like cancer to be seen as more of a chronic disease so that living with cancer would be just like living with diabetes or any other chronic illness," says MacDonald.

"A year maybe doesn't sound like a long time to some people. But in a dog's life, a year – especially a quality year – is a substantially long time. I don't think I've had any clients that regretted treating their dogs."