Brachyspira research: linking diarrhea to DNA

How do you get a pathologist, a physiologist, a microbiologist and a large animal clinician to work together?

By Gabrielle Paul-McKenzie

Ask them to investigate a diarrhea-causing, production-limiting bacteria of pigs that goes by the name of Brachyspira.

I spent my summer as part of a multi-disciplinary research team at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) that's targeting Brachyspira. The group's ultimate goal is to develop better diagnostic tools along with a better understanding of how this spiral-shaped bug causes disease in pigs.

Brachyspira is a type of bacteria that causes bloody, mucous-filled diarrhea in pigs. Though the bacterial disease is seldom fatal, it does slow the growth of pigs and can have devastating economic effects in a barn of growing animals. Its recent emergence in Western Canada has made it a serious concern for swine producers.

Several species of Brachyspira are known to exist. Though some species can cause serious illness in pigs, others are harmless and may exist as normal members of the pig's intestinal microbiota.

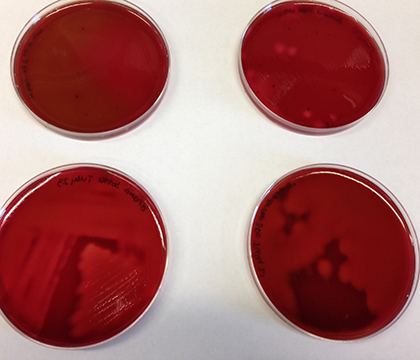

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of Brachyspira is the bacteria's ability to burst red blood cells, a phenomenon called hemolysis. When researchers grow the bacteria on blood agar growth medium plates in the lab, it will change the normally red plate to translucent by causing hemolysis of the red blood cells that are contained in the plate. Scientists classify bacteria with this ability as being beta-hemolytic.

It's possible to distinguish between species of Brachyspira based on the quality of their beta-hemolysis. A "strongly hemolytic" species of the bacteria will cause a dramatic clearing of blood plates, leaving the plates so translucent that you could easily read the Sunday newspaper through them.

A "weakly hemolytic" species of Brachyspira will cause a less dramatic clearing, leaving the plates opaque and difficult to see through.

For years, scientists have used the different patterns of hemolysis as a diagnostic tool in characterizing different species of Brachyspira. But there are several problems associated with this identification method. One key issue is that there's no way to definitively quantify (or describe) the amount of hemolysis. "Strong" and "weak" are subjective terms that don't do justice to the wide variety of hemolysis patterns exhibited by known species and isolates of Brachyspira.

"Hemolysis is an important diagnostic characteristic of Brachyspira that has been traditionally associated with virulence. However, the more field isolates and clinical isolates we look at in the lab, the more we understand that hemolysis is not just ‘strong' or ‘weak,'" says Dr. Janet Hill, an associate professor in the WCVM's Department of Veterinary Microbiology and my research supervisor.

"In order to more fully characterize clinical isolates, we need a way to measure hemolysis objectively."

Working with Hill, I've spent a large part of my summer trying to develop a working protocol to quantify hemolysis, known as a "hemolysis assay." Ultimately, we hope to apply this new test to everyday diagnostic work on Brachyspira in the lab.

Another issue with using hemolysis as a means of bacterial identification came up after members of Hill's research lab discovered a surprising variety of Brachyspira in healthy pigs on a western Canadian farm.

While all of these new bacteria isolates likely belong to the same species, they appear to exhibit different degrees of hemolysis.

Part of my summer's work includes sequencing the full genome of one of these strongly hemolytic Brachyspira isolates so it can be compared with the genome of a weakly hemolytic isolate that has already been sequenced.

Both of these isolates ultimately belong to the same species of Brachyspira, and a comparison of their genomes may give us insight into the specific genes that control hemolysis.

Some scientists suggest that the hemolytic ability of different types of Brachyspira is associated with virulence — the stronger the hemolysis, the stronger the virulence.

While this relationship hasn't yet been extensively demonstrated, a greater understanding of what makes one strain more hemolytic than another could lead to a greater understanding of the larger question: what makes one strain more virulent than another?

If researchers can identify genes controlling virulence, they can eventually develop diagnostic testing that will be used to test samples from affected farms and determine which bacteria is present and its virulence level.

Quantifying hemolysis and understanding factors associated with virulence is only a small part of the ongoing Brachyspira research at the WCVM. The research team's eventual goal is to understand the pathogenesis of the disease and to ultimately control and prevent its spread in Western Canada.

Gabrielle Paul-McKenzie of Prince Albert, Sask., is a second-year veterinary student who was part of the WCVM's Undergraduate Summer Research and Leadership program in 2014. Gabrielle's story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.

I spent my summer as part of a multi-disciplinary research team at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) that's targeting Brachyspira. The group's ultimate goal is to develop better diagnostic tools along with a better understanding of how this spiral-shaped bug causes disease in pigs.

Brachyspira is a type of bacteria that causes bloody, mucous-filled diarrhea in pigs. Though the bacterial disease is seldom fatal, it does slow the growth of pigs and can have devastating economic effects in a barn of growing animals. Its recent emergence in Western Canada has made it a serious concern for swine producers.

Several species of Brachyspira are known to exist. Though some species can cause serious illness in pigs, others are harmless and may exist as normal members of the pig's intestinal microbiota.

Perhaps the most distinctive characteristic of Brachyspira is the bacteria's ability to burst red blood cells, a phenomenon called hemolysis. When researchers grow the bacteria on blood agar growth medium plates in the lab, it will change the normally red plate to translucent by causing hemolysis of the red blood cells that are contained in the plate. Scientists classify bacteria with this ability as being beta-hemolytic.

It's possible to distinguish between species of Brachyspira based on the quality of their beta-hemolysis. A "strongly hemolytic" species of the bacteria will cause a dramatic clearing of blood plates, leaving the plates so translucent that you could easily read the Sunday newspaper through them.

A "weakly hemolytic" species of Brachyspira will cause a less dramatic clearing, leaving the plates opaque and difficult to see through.

For years, scientists have used the different patterns of hemolysis as a diagnostic tool in characterizing different species of Brachyspira. But there are several problems associated with this identification method. One key issue is that there's no way to definitively quantify (or describe) the amount of hemolysis. "Strong" and "weak" are subjective terms that don't do justice to the wide variety of hemolysis patterns exhibited by known species and isolates of Brachyspira.

"Hemolysis is an important diagnostic characteristic of Brachyspira that has been traditionally associated with virulence. However, the more field isolates and clinical isolates we look at in the lab, the more we understand that hemolysis is not just ‘strong' or ‘weak,'" says Dr. Janet Hill, an associate professor in the WCVM's Department of Veterinary Microbiology and my research supervisor.

"In order to more fully characterize clinical isolates, we need a way to measure hemolysis objectively."

Working with Hill, I've spent a large part of my summer trying to develop a working protocol to quantify hemolysis, known as a "hemolysis assay." Ultimately, we hope to apply this new test to everyday diagnostic work on Brachyspira in the lab.

Another issue with using hemolysis as a means of bacterial identification came up after members of Hill's research lab discovered a surprising variety of Brachyspira in healthy pigs on a western Canadian farm.

While all of these new bacteria isolates likely belong to the same species, they appear to exhibit different degrees of hemolysis.

Part of my summer's work includes sequencing the full genome of one of these strongly hemolytic Brachyspira isolates so it can be compared with the genome of a weakly hemolytic isolate that has already been sequenced.

Both of these isolates ultimately belong to the same species of Brachyspira, and a comparison of their genomes may give us insight into the specific genes that control hemolysis.

Some scientists suggest that the hemolytic ability of different types of Brachyspira is associated with virulence — the stronger the hemolysis, the stronger the virulence.

While this relationship hasn't yet been extensively demonstrated, a greater understanding of what makes one strain more hemolytic than another could lead to a greater understanding of the larger question: what makes one strain more virulent than another?

If researchers can identify genes controlling virulence, they can eventually develop diagnostic testing that will be used to test samples from affected farms and determine which bacteria is present and its virulence level.

Quantifying hemolysis and understanding factors associated with virulence is only a small part of the ongoing Brachyspira research at the WCVM. The research team's eventual goal is to understand the pathogenesis of the disease and to ultimately control and prevent its spread in Western Canada.

Gabrielle Paul-McKenzie of Prince Albert, Sask., is a second-year veterinary student who was part of the WCVM's Undergraduate Summer Research and Leadership program in 2014. Gabrielle's story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.