Horse survives after stick impales chest

On a dark October night, Les and Darlene Leer pulled into the parking lot at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine's Veterinary Medical Centre in Saskatoon with their horse trailer in tow.

By Christina Weese

It was late, and they were worried. They had made the three-hour drive from St. Walburg, Sask., to bring in their injured 18-year-old Appaloosa gelding, Tuffy, for emergency care.

A few days earlier Darlene Leer had gone looking for Tuffy, her retired saddle horse, and found him in their neighbor's pasture with a two-foot stick lodged in his chest cavity.

Darlene called their local veterinarian — Dr. Melissa Knowles of Northwest Veterinary Services in nearby Turtleford. Knowles carefully removed the stick, cleaned Tuffy's wound and started him on antibiotics — but the gelding wasn't improving. His breathing became laboured and faster, and he was losing interest in eating and drinking.

As Knowles grew more concerned, she recommended that the Leers take Tuffy to the WCVM's Large Animal Clinic.

When Tuffy arrived at the WCVM, the clinical team found that his breathing was rapid and his heart rate was elevated. Normally, horses take about 10 to 12 breaths per minute and have a heart rate of 28 to 44 beats per minute (bpm). Tuffy's vital signs were 40 breaths per minute with a heart rate of 60 bpm.

"He was very close to not making it," says Dr. Fernando Marqués, a specialist in large animal internal medicine at the WCVM. He and his resident, Dr. Sara Higgins, were on duty the night of Tuffy's arrival.

After a thorough physical examination, the WCVM clinicians ordered tests, and the results weren't encouraging. An ultrasound exam and radiographs confirmed the diagnosis of pleural effusion and pneumothorax (a build up of fluid and air in the pleural

cavity, the thin space between the lung and chest). Normally there is negative pressure (with no air present) in the pleural cavity, allowing the lung to expand and inflate during respiration. The horse was also suffering from mild pneumonia and ventricular tachycardia (an abnormal heart rhythm).

The combination of air and fluid induced an increased pressure in Tuffy's pleural cavity (see video link), causing a collapsed lung and an irregular heartbeat.

"They were very efficient at telling us what was going on," says Darlene. "I was amazed at the care they took in telling us, the owners, what they were doing and what the scenarios were — both what they were seeing and what could potentially happen."

The WCVM clinical team immediately performed several actions to improve Tuffy's situation. To ensure that his chest wound wasn't potentially letting air into the pleural cavity, they stapled a plastic covering, held in place with a gauze roll, around the edges of the wound to help seal the entry point.

The team also placed indwelling chest tubes to drain fluid from Tuffy's pleural cavity, and during that first night, 12 litres of fluid was collected. In his stall, Tuffy was also put on intravenous fluids and a broad spectrum of antibiotic drugs. He was also connected to an ECG machine with telemetry capabilities, allowing for continuous and real-time heart rate monitoring from a remote computer.

The clinicians placed a second set of indwelling chest tubes on the upper portion of Tuffy's chest to drain the air from the pleural cavity, Once a day for three days, the team hooked up the horse to a suction pump to remove excess air from his pleural cavity and to re-inflate his collapsed lung. But it wasn't enough: Higgins and Marqués suspected damage to the lung itself was causing air to leak from the lung into the chest cavity.

That's when Marqués, Higgins and Clark came across an idea that likely saved Tuffy's life.

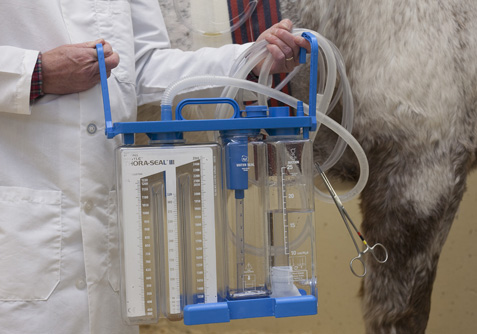

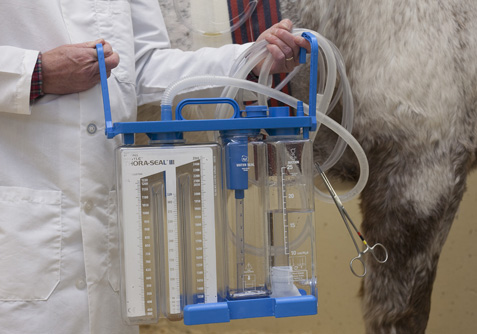

"The WCVM uses a device called Thora-Seal™ (a chest drainage unit) in small animal practice with great success," Marqués explains. "Knowing that the device was available to us, we wanted to use it for Tuffy. If we can keep the lungs inflated by removing the air constantly from the pleural space, it gives them a chance to heal better and faster."

Originally designed for use in people, the Thora-Seal™ connects to a continuous suction pump with the advantage of monitoring and constantly maintaining proper pressure in the pleural cavity, since too much pressure can be just as detrimental as not enough.

WCVM clinicians attached the device to Tuffy's indwelling tubes through an overhead line in his stall. Miraculously, he began to heal. After five days, the tubes were pinched shut, and Tuffy was carefully monitored to see if he would improve on his own.

Marqués and Higgins add that it takes teamwork to bring about a successful outcome in challenging cases such as this one; when an animal needs 24/7 care, residents, interns, veterinary technologists and veterinary students play an important role. Large animal internal medicine intern Dr. Felicity Wills — along with veterinary technologists Sherry Presnell and Rebecca Johnston — all played a key part in Tuffy's recovery. Additional support came from fourth-year veterinary students Trinita Barboza, Larissa Goodman and Candace Wenzel.

"I thought it was a really challenging case," admits Marqués. "With all the care that we provided, and with the cutting edge technology we have available here to provide that care, this horse was able to make it."

On Nov. 6, after 15 days in the hospital, Tuffy was discharged and sent home with his happy owners.

"I can't say enough about their dedication and teamwork, and the willingness of people to learn," says Darlene. "[When we arrived with Tuffy,] Les asked if all the people there were the night staff, but no, they just came because they heard this case was coming in."

Back in his pasture at St. Walburg, Tuffy is doing well.

"He's got his own little blanket because he had a shaved side, and he's out with his friend Rascal," says Darlene. "He's getting his attitude back. He's back to his old self again."

A few days earlier Darlene Leer had gone looking for Tuffy, her retired saddle horse, and found him in their neighbor's pasture with a two-foot stick lodged in his chest cavity.

Darlene called their local veterinarian — Dr. Melissa Knowles of Northwest Veterinary Services in nearby Turtleford. Knowles carefully removed the stick, cleaned Tuffy's wound and started him on antibiotics — but the gelding wasn't improving. His breathing became laboured and faster, and he was losing interest in eating and drinking.

As Knowles grew more concerned, she recommended that the Leers take Tuffy to the WCVM's Large Animal Clinic.

When Tuffy arrived at the WCVM, the clinical team found that his breathing was rapid and his heart rate was elevated. Normally, horses take about 10 to 12 breaths per minute and have a heart rate of 28 to 44 beats per minute (bpm). Tuffy's vital signs were 40 breaths per minute with a heart rate of 60 bpm.

WATCH a video of Tuffy with WCVM professor Dr. Fernando Marqués at the WCVM Veterinary Medical Centre.

"He was very close to not making it," says Dr. Fernando Marqués, a specialist in large animal internal medicine at the WCVM. He and his resident, Dr. Sara Higgins, were on duty the night of Tuffy's arrival.

After a thorough physical examination, the WCVM clinicians ordered tests, and the results weren't encouraging. An ultrasound exam and radiographs confirmed the diagnosis of pleural effusion and pneumothorax (a build up of fluid and air in the pleural

cavity, the thin space between the lung and chest). Normally there is negative pressure (with no air present) in the pleural cavity, allowing the lung to expand and inflate during respiration. The horse was also suffering from mild pneumonia and ventricular tachycardia (an abnormal heart rhythm).

The combination of air and fluid induced an increased pressure in Tuffy's pleural cavity (see video link), causing a collapsed lung and an irregular heartbeat.

"They were very efficient at telling us what was going on," says Darlene. "I was amazed at the care they took in telling us, the owners, what they were doing and what the scenarios were — both what they were seeing and what could potentially happen."

The WCVM clinical team immediately performed several actions to improve Tuffy's situation. To ensure that his chest wound wasn't potentially letting air into the pleural cavity, they stapled a plastic covering, held in place with a gauze roll, around the edges of the wound to help seal the entry point.

The team also placed indwelling chest tubes to drain fluid from Tuffy's pleural cavity, and during that first night, 12 litres of fluid was collected. In his stall, Tuffy was also put on intravenous fluids and a broad spectrum of antibiotic drugs. He was also connected to an ECG machine with telemetry capabilities, allowing for continuous and real-time heart rate monitoring from a remote computer.

The clinicians placed a second set of indwelling chest tubes on the upper portion of Tuffy's chest to drain the air from the pleural cavity, Once a day for three days, the team hooked up the horse to a suction pump to remove excess air from his pleural cavity and to re-inflate his collapsed lung. But it wasn't enough: Higgins and Marqués suspected damage to the lung itself was causing air to leak from the lung into the chest cavity.

That's when Marqués, Higgins and Clark came across an idea that likely saved Tuffy's life.

"The WCVM uses a device called Thora-Seal™ (a chest drainage unit) in small animal practice with great success," Marqués explains. "Knowing that the device was available to us, we wanted to use it for Tuffy. If we can keep the lungs inflated by removing the air constantly from the pleural space, it gives them a chance to heal better and faster."

Originally designed for use in people, the Thora-Seal™ connects to a continuous suction pump with the advantage of monitoring and constantly maintaining proper pressure in the pleural cavity, since too much pressure can be just as detrimental as not enough.

WCVM clinicians attached the device to Tuffy's indwelling tubes through an overhead line in his stall. Miraculously, he began to heal. After five days, the tubes were pinched shut, and Tuffy was carefully monitored to see if he would improve on his own.

Marqués and Higgins add that it takes teamwork to bring about a successful outcome in challenging cases such as this one; when an animal needs 24/7 care, residents, interns, veterinary technologists and veterinary students play an important role. Large animal internal medicine intern Dr. Felicity Wills — along with veterinary technologists Sherry Presnell and Rebecca Johnston — all played a key part in Tuffy's recovery. Additional support came from fourth-year veterinary students Trinita Barboza, Larissa Goodman and Candace Wenzel.

"I thought it was a really challenging case," admits Marqués. "With all the care that we provided, and with the cutting edge technology we have available here to provide that care, this horse was able to make it."

On Nov. 6, after 15 days in the hospital, Tuffy was discharged and sent home with his happy owners.

"I can't say enough about their dedication and teamwork, and the willingness of people to learn," says Darlene. "[When we arrived with Tuffy,] Les asked if all the people there were the night staff, but no, they just came because they heard this case was coming in."

Back in his pasture at St. Walburg, Tuffy is doing well.

"He's got his own little blanket because he had a shaved side, and he's out with his friend Rascal," says Darlene. "He's getting his attitude back. He's back to his old self again."