Bolt flies free

Dr. Brandy Kragness let go of the wild bird she had cared for all winter and watched "Bolt" swiftly launch himself into the wind, flying strong and sure across the stubble field.

By Jeanette Neufeld

It was an exhilarating moment for Kragness, a clinical intern in zoological, exotic and wildlife medicine at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine's (WCVM) Veterinary Medical Centre. She had seen Bolt at his weakest – admitting the bird to the college on the day a civilian brought him in with a broken wing in September 2015. She also performed surgery on the bird and was part of his long recovery every step of the way.

"This is the best [bird] release of the year — definitely," says Kragness after Bolt flew away.

The wildlife team released the northern harrier, a type of long, slim-tailed hawk, near Osler, Sask,, where he was found eight months ago. Unable to fly, the injured bird had puncture wounds, a fractured wing and broken tail feathers.

After he was brought to the medical centre, WCVM veterinarians examined the bird and X-rayed the fractured wing. They treated and bandaged Bolt's wound and then gave him pain and anti-inflammatory medications as well as fluids under the skin and antibiotic drugs.

Northern harriers – a bird of prey belonging to the raptor classification – typically spend the colder months of the year in the southern United States, sometimes travelling as far as South America.

Instead Bolt spent the winter at the WCVM, recovering from surgery on his fractured wing and receiving rehabilitative treatments including laser therapy to help stimulate cells and speed up healing. As the months went by, the juvenile bird grew into an adult under the veterinary team's care.

"Captivity-related injuries and illnesses can happen with wild birds, so we're just really happy that he made it well through the winter because sometimes that can affect them, too," says Dr. Miranda Sadar, assistant professor of exotic, wildlife and zoological medicine at the WCVM.

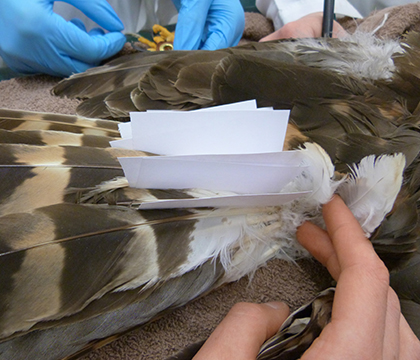

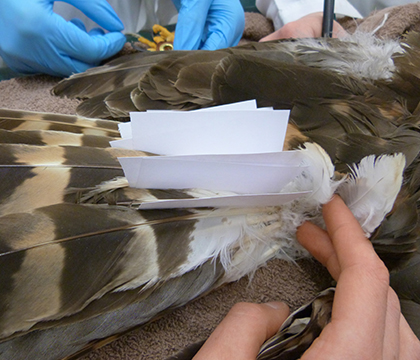

In late April the wildlife veterinarians conducted a tail feather transplant on the bird, affixing donor feathers from a deceased bird of the same age and species. The technique, called "imping," was a first for many of the WCVM staff and students involved in the procedure.

"None of the students had seen imping before or participated in it. Each of them got to do a feather, all of them got to see the process and learn the process so they will be better equipped to go out and do this in practice," says Sadar, who learned about imping during her two-year fellowship at the Wildlife Center of Virginia.

During the 90-minute procedure, team members carefully cut each donor feather to match the broken tail feather and affixed every one using epoxy and bamboo sticks. Ideally these feathers will last until Bolt molts again, with new ones growing in their place.

To prepare him for release, Kragness and other team members used a technique called creancing. This method allowed Bolt to fly freely but still be connected to his caregivers through a long line attached to an anklet on his leg. The team took Bolt out to a nearby field every day and let him fly for longer periods each time.

"It's just like us getting ready for a marathon — it's really important to get his muscles and stamina up to speed," says Sadar.

By the end of April, the team knew Bolt was ready to go. He was showing no signs of pain or tiring while flying.

Bolt's recovery was a team effort that involved a variety of VMC staff as well as clinical interns and veterinary students.

"Basically, it was great learning for both the interns and students. For the interns, they got to fix this bird's fracture surgically and also got to manage him long term," says Sadar. "It was [also] a good learning experience for our rehab folks … they've got so much more information than they did previously just based on how long he was here and how he responded to the rehab and the lasering."

Shortly before Bolt was released, the bird received a band around its ankle. The band provides instructions about who to contact if Bolt is ever found by a member of the public. When dealing with wildlife, the best-case scenario is bittersweet.

"Hopefully we will never hear from him again," says Sadar.

Due to the high cost of treating rescued wildlife, the WCVM's Veterinary Medical Centre is always seeking donations to support wildlife cases such as this one. Visit https://give.usask.ca/online/wcvm.php to make a donation.

https://vimeo.com/166238774

"This is the best [bird] release of the year — definitely," says Kragness after Bolt flew away.

The wildlife team released the northern harrier, a type of long, slim-tailed hawk, near Osler, Sask,, where he was found eight months ago. Unable to fly, the injured bird had puncture wounds, a fractured wing and broken tail feathers.

After he was brought to the medical centre, WCVM veterinarians examined the bird and X-rayed the fractured wing. They treated and bandaged Bolt's wound and then gave him pain and anti-inflammatory medications as well as fluids under the skin and antibiotic drugs.

Northern harriers – a bird of prey belonging to the raptor classification – typically spend the colder months of the year in the southern United States, sometimes travelling as far as South America.

Instead Bolt spent the winter at the WCVM, recovering from surgery on his fractured wing and receiving rehabilitative treatments including laser therapy to help stimulate cells and speed up healing. As the months went by, the juvenile bird grew into an adult under the veterinary team's care.

"Captivity-related injuries and illnesses can happen with wild birds, so we're just really happy that he made it well through the winter because sometimes that can affect them, too," says Dr. Miranda Sadar, assistant professor of exotic, wildlife and zoological medicine at the WCVM.

In late April the wildlife veterinarians conducted a tail feather transplant on the bird, affixing donor feathers from a deceased bird of the same age and species. The technique, called "imping," was a first for many of the WCVM staff and students involved in the procedure.

"None of the students had seen imping before or participated in it. Each of them got to do a feather, all of them got to see the process and learn the process so they will be better equipped to go out and do this in practice," says Sadar, who learned about imping during her two-year fellowship at the Wildlife Center of Virginia.

During the 90-minute procedure, team members carefully cut each donor feather to match the broken tail feather and affixed every one using epoxy and bamboo sticks. Ideally these feathers will last until Bolt molts again, with new ones growing in their place.

To prepare him for release, Kragness and other team members used a technique called creancing. This method allowed Bolt to fly freely but still be connected to his caregivers through a long line attached to an anklet on his leg. The team took Bolt out to a nearby field every day and let him fly for longer periods each time.

"It's just like us getting ready for a marathon — it's really important to get his muscles and stamina up to speed," says Sadar.

By the end of April, the team knew Bolt was ready to go. He was showing no signs of pain or tiring while flying.

Bolt's recovery was a team effort that involved a variety of VMC staff as well as clinical interns and veterinary students.

"Basically, it was great learning for both the interns and students. For the interns, they got to fix this bird's fracture surgically and also got to manage him long term," says Sadar. "It was [also] a good learning experience for our rehab folks … they've got so much more information than they did previously just based on how long he was here and how he responded to the rehab and the lasering."

Shortly before Bolt was released, the bird received a band around its ankle. The band provides instructions about who to contact if Bolt is ever found by a member of the public. When dealing with wildlife, the best-case scenario is bittersweet.

"Hopefully we will never hear from him again," says Sadar.

Due to the high cost of treating rescued wildlife, the WCVM's Veterinary Medical Centre is always seeking donations to support wildlife cases such as this one. Visit https://give.usask.ca/online/wcvm.php to make a donation.

https://vimeo.com/166238774