Sable Island horses buck bacteria trend

Could bacteria resistant to antimicrobial drugs routinely used in both human and veterinary medicine be found in wild horses on a remote island in the Atlantic Ocean?

By Mary Timonin

By answering this question, Dr. Joe Rubin and members of his research team at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) hope to gain a better understanding of how bacteria carrying acquired resistance genes are passed between humans, domestic animals and wildlife species.

Their research has two major players: the horses living on Sable Island and the "bugs" — specifically Escherichia coli (E. coli) that these horses carry in their guts.

Sable Island, located 160 kilometres off Canada's Atlantic coast, is home to a population of over 500 feral horses – one of only a handful of wild horse populations in the world. The herd is descended from horses brought to the island in the late 1700s and has been protected by law from human interference since the 1960s.

These horses provide unique opportunities for researchers to study horse behaviour and health, as well as broader questions in ecology and evolution. They also represent a baseline population to study acquired antimicrobial resistance.

Rubin, an assistant professor in the WCVM's Department of Veterinary Microbiology, recognized the potential of the Sable Island horses to answer questions about how drug resistance spreads between bacteria as well as between animals.

The horses' isolated geographic location, their limited exposure to other species (including humans) and a complete lack of antibiotic exposure in the history of the herd are all factors that make this horse population so unique.

"The pressure for antimicrobial resistance and the potential exposure to resistant organisms from other animal species is quite limited," says Rubin.

Looking for acquired resistance in bacteria cultured from wildlife isn't a new concept, but the majority of studies have focused on birds or other species that interact with humans or agricultural production – increasing the potential for exposure to antimicrobial drugs or resistant bacteria.

Researchers frequently use E. coli in these surveillance studies for several reasons: it's found in the guts of most animals, it's easy to grow and it has many standardized tests established for its identification. E. coli also has the ability to accept and pass on resistance genes located on small pieces of DNA called plasmids that can be transferred between bacteria. Drug-resistant E. coli have been successfully cultured from a variety of wildlife species, and wildlife populations act as a reservoir for these resistance genes.

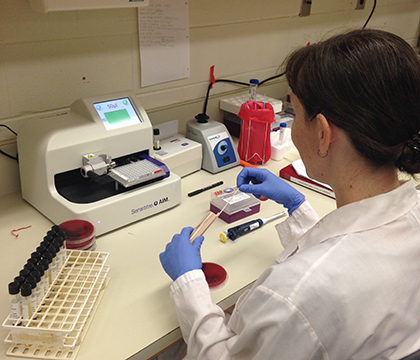

To determine if the Sable Island horses are acting as a reservoir for E. coli-carrying drug resistance genes, Rubin and his team used fecal samples collected from members of the equine herd. The collected samples are part of a multi-disciplinary Sable Island horse "gut biome" research project involving researchers from the University of Saskatchewan as well as other universities in Canada and abroad.

Researchers attempted to grow E. coli from each of these fecal samples. Next they tried to kill the bugs with a broad range of antimicrobial agents used in human and veterinary medicine. By keeping track of which antimicrobial drugs were effective in killing off the bugs and which were less effective, the scientists could develop a susceptibility profile for each isolated E. coli sample.

The WCVM researchers also have the ability to link back each E. coli sample grown in the study to the individual horse from which it was originally isolated. Researchers have been collecting census-level data on these horses since 2008, including family relationships between horses, geographic location on the island where the horses live and the social group they associate with.

"We actually know something about every single animal on the island," says Rubin.

This astounding depth and breadth of ecological data provides researchers with a unique opportunity to study the spread of bacteria carrying acquired resistance genes within an animal population. It also allows researchers to address questions such as whether bugs are shared within a family group, or the role of the environmental niche occupied by horses on the island.

Do the Sable Island horses represent a wildlife reservoir for resistance genes?

The simple answer appears to be no. Of the 500-plus fecal samples processed by Rubin and his research team, only a handful showed growth of E. coli at all — and those E. coli were "wimpy." In other words, the bacteria were unable to grow when exposed to even low concentrations of antimicrobial drugs.

For Rubin, the remarkably low levels of E. coli colonization (found in less than 30 per cent of the horse population) was one of the study's most surprising results — and it's one that he intends to pursue with more detailed analyses.

So far, it seems the same factors that make the Sable Island horses a unique microbiological benchmark population have been effective in protecting these horses from drug-resistant bacteria. But for how long? As more people visit Sable Island — Canada's newest national park reserve — and the number of drug-resistant bacteria present in migratory animals such as seals and wild birds rises, antimicrobial-resistant bacteria may soon become another part of the horses' remote world.

This study is supported by the Heather Ryan and L. David Dubé Veterinary Health and Research Fund.

Mary Timonin of Winnipeg, Man., is a second-year veterinary student who was part of the WCVM's Undergraduate Summer Research and Leadership program in 2015. Mary's story is part of a series of stories written by WCVM summer research students.

Their research has two major players: the horses living on Sable Island and the "bugs" — specifically Escherichia coli (E. coli) that these horses carry in their guts.

Sable Island, located 160 kilometres off Canada's Atlantic coast, is home to a population of over 500 feral horses – one of only a handful of wild horse populations in the world. The herd is descended from horses brought to the island in the late 1700s and has been protected by law from human interference since the 1960s.

These horses provide unique opportunities for researchers to study horse behaviour and health, as well as broader questions in ecology and evolution. They also represent a baseline population to study acquired antimicrobial resistance.

Rubin, an assistant professor in the WCVM's Department of Veterinary Microbiology, recognized the potential of the Sable Island horses to answer questions about how drug resistance spreads between bacteria as well as between animals.

The horses' isolated geographic location, their limited exposure to other species (including humans) and a complete lack of antibiotic exposure in the history of the herd are all factors that make this horse population so unique.

"The pressure for antimicrobial resistance and the potential exposure to resistant organisms from other animal species is quite limited," says Rubin.

Looking for acquired resistance in bacteria cultured from wildlife isn't a new concept, but the majority of studies have focused on birds or other species that interact with humans or agricultural production – increasing the potential for exposure to antimicrobial drugs or resistant bacteria.

Researchers frequently use E. coli in these surveillance studies for several reasons: it's found in the guts of most animals, it's easy to grow and it has many standardized tests established for its identification. E. coli also has the ability to accept and pass on resistance genes located on small pieces of DNA called plasmids that can be transferred between bacteria. Drug-resistant E. coli have been successfully cultured from a variety of wildlife species, and wildlife populations act as a reservoir for these resistance genes.

To determine if the Sable Island horses are acting as a reservoir for E. coli-carrying drug resistance genes, Rubin and his team used fecal samples collected from members of the equine herd. The collected samples are part of a multi-disciplinary Sable Island horse "gut biome" research project involving researchers from the University of Saskatchewan as well as other universities in Canada and abroad.

Researchers attempted to grow E. coli from each of these fecal samples. Next they tried to kill the bugs with a broad range of antimicrobial agents used in human and veterinary medicine. By keeping track of which antimicrobial drugs were effective in killing off the bugs and which were less effective, the scientists could develop a susceptibility profile for each isolated E. coli sample.

The WCVM researchers also have the ability to link back each E. coli sample grown in the study to the individual horse from which it was originally isolated. Researchers have been collecting census-level data on these horses since 2008, including family relationships between horses, geographic location on the island where the horses live and the social group they associate with.

"We actually know something about every single animal on the island," says Rubin.

This astounding depth and breadth of ecological data provides researchers with a unique opportunity to study the spread of bacteria carrying acquired resistance genes within an animal population. It also allows researchers to address questions such as whether bugs are shared within a family group, or the role of the environmental niche occupied by horses on the island.

Do the Sable Island horses represent a wildlife reservoir for resistance genes?

The simple answer appears to be no. Of the 500-plus fecal samples processed by Rubin and his research team, only a handful showed growth of E. coli at all — and those E. coli were "wimpy." In other words, the bacteria were unable to grow when exposed to even low concentrations of antimicrobial drugs.

For Rubin, the remarkably low levels of E. coli colonization (found in less than 30 per cent of the horse population) was one of the study's most surprising results — and it's one that he intends to pursue with more detailed analyses.

So far, it seems the same factors that make the Sable Island horses a unique microbiological benchmark population have been effective in protecting these horses from drug-resistant bacteria. But for how long? As more people visit Sable Island — Canada's newest national park reserve — and the number of drug-resistant bacteria present in migratory animals such as seals and wild birds rises, antimicrobial-resistant bacteria may soon become another part of the horses' remote world.

This study is supported by the Heather Ryan and L. David Dubé Veterinary Health and Research Fund.

Mary Timonin of Winnipeg, Man., is a second-year veterinary student who was part of the WCVM's Undergraduate Summer Research and Leadership program in 2015. Mary's story is part of a series of stories written by WCVM summer research students.