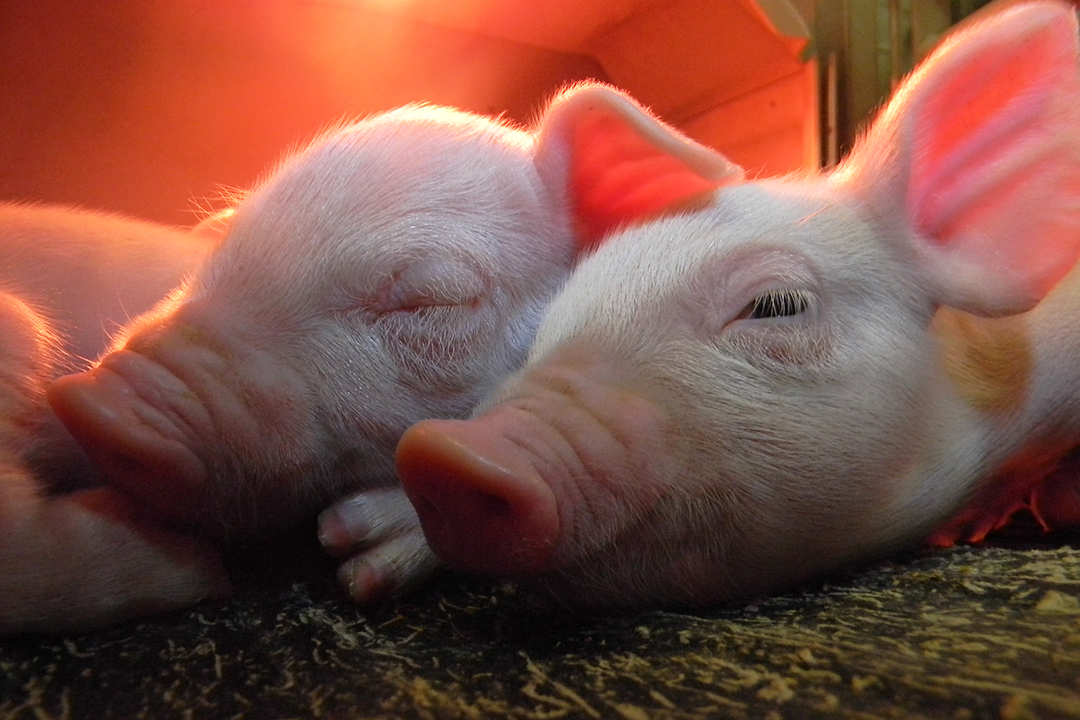

Pigs came calling for WCVM graduate

When Dr. Blaine Tully graduated from the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), it was a given that he would return to his home province of Manitoba. Home and family beckoned.

By Kathy Fitzpatrick

No one — not even Tully — expected the direction his career would take.

Having grown up on a dairy farm, his vet school professors and classmates knew him as a “cow guy.” After graduating in 2001, Tully joined a mixed animal practice that included dairy and beef cattle clients as well as a steady caseload of companion animals.

Within his first year, he knew mixed animal practice wasn’t for him. A single parent, he found the emergency calls especially tough: “I really wasn’t wired for handling those curve balls.”

And, he yearned to do more problem solving.

Tully found his life-altering opportunity in a chance meeting with Dr. Brad Chappell, a 1998 WCVM graduate and now his practice partner at Swine Health Professionals in Steinbach, Man.

The opportunity to work exclusively with farmers “was a huge draw for me,” Tully says. “I’ve always been quite passionate about agriculture and food production.”

Swine practice also feeds his interest in population medicine and epidemiology. Keeping pigs healthy and productive is a “multi-faceted and complex” task, Tully explains, drawing in such elements as farm infrastructure, the flow of animals from one segment of the operation to another, and management of animal groupings.

For example, Tully notes how the industry has rethought the best time to wean piglets. At 18 days old, a piglet’s intestinal tract is not quite ready to digest solid plant-based proteins. Rather than focusing on average wean ages, Tully and his colleagues have helped their swine clients work to narrow the range from 19 to 27 days old to a range from 21 to 25 days old. For Tully, helping producers understand management strategies to achieve these goals and improve pig health has been very rewarding.

In applying the latest knowledge, Tully draws on his alma mater — the WCVM.

“Having [Professor] John Harding as the swine specialist in Saskatoon is a pretty big deal for Western Canada, I feel,” Tully says. “He’s really known for work in circovirus, Brachyspira diseases and PRRS [porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome] transmission on farms. And so having him as a resource to tap into when we do run into farm challenges, it’s a pretty important piece of western Canadian swine practices.”

As well, Tully and his partners routinely rely on a laboratory test offered at the WCVM, which identifies different species of Brachyspira. Tully notes the work of WCVM microbiologist Janet Hill in helping to develop the test.

Tully’s unflagging passion for swine medicine is obvious.

“I really love what I do,” he says. “I’m fortunate in working within our practice with just a fantastic group of people.”

In addition to Chappell and Tully, Swine Health Professionals’ veterinary team includes Dr. Wadie Ariza as well as two other WCVM graduates — Drs. Jennifer Demare and Judy Hodge.

He also enjoys helping farmers take pride in the fruits of their labour – putting it not just in terms of the number of pigs sold in a year, but in how many pork meals they produce for the world.

It’s a well-earned pride: “Canadian hog producers are amongst the best in the world,” Tully says.

Looking back, he admits surprise at how his career turned out.

“My kids tell me, ‘Remember when you used to be a real vet, Dad?’”

He doesn’t quite know where that notion of veterinarians comes from – maybe from a mental image of pet owners taking their animals in to see clinicians in white coats, or Dr. James Herriot traversing the misty English countryside.

As a swine practitioner, Tully puts in a lot of “windshield time,” covering large distances across Manitoba. In a typical week, he figures he puts in 50 to 60 hours of actual practice. “We work long hours, but they’re our hours,” he says.

In 17 years of practising swine medicine, Tully has gone out on exactly four weekend emergency calls.

“That to me is priceless as well.”