Saliva test could lead to better parasite control

Researchers at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) are looking for a more accurate way to detect internal parasites in beef cattle by looking at the animals’ saliva.

By Courtney Orsen

The most common method to detect internal parasites is to perform a fecal egg count. This practice involves counting parasite eggs in feces collected from cattle, but it has some issues.

Fecal egg counts only give an indication of the amount of adult female parasites are in the cow; they do not indicate the number of adult males or the younger stages of parasites that may also be damaging to the animal. Additionally, the test isn’t as accurate when a cow’s fecal egg counts are low.

But if researchers could relate the level of antibodies in the saliva to the amount of internal parasites and to production performance, then the level of antibodies could guide deworming treatment.

Potentially, this means that producers and veterinarians could simply swab the inside of cattle’s mouths, send the samples to the lab and then set up their parasite management program based on the test results.

Developing this test could also lead to potential advancements in parasite research. For example, it could enable scientists to establish a “cut off” or baseline that would show producers when it would be economically beneficial to deworm their cattle.

“If you determine which animals need treatment, which may be tricky, but for long-term sustainable management and wanting to reduce resistance development, this is one of the major contributions in doing that,” says Eranga De Seram, a PhD student at the WCVM.

De Seram explains that because Western Canada has a low level of internal parasites, it’s critical for researchers to develop a more sensitive and accurate test for parasite detection — something that’s lacking in the region right now.

While parasite levels are low, cattle producers should still be concerned because there are some very damaging parasites in the West, he adds.

“Ostertagia ostertagi is the most predominant nematode species in Canadian soil,” says De Seram. Although this parasite doesn’t produce a large number of eggs, it’s one of the most devastating parasites in terms of affecting the production performance of cattle.

This is one of the main reasons why Dr. Fabienne Uehlinger, an assistant professor in the WCVM’s Department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences, and her research team — including De Seram, her graduate student — are working on this study in Canada. Although the saliva test was developed for use in sheep in New Zealand and has been applied to cattle in France, this is a first for Canada.

The WCVM team is running this saliva test on about 45 Canadian beef cattle and comparing the results to fecal egg counts, antibodies in the animals’ blood and their weight gains. Since the number of parasites on pastures increases over time, the researchers have been collecting numerous samples throughout the summer.

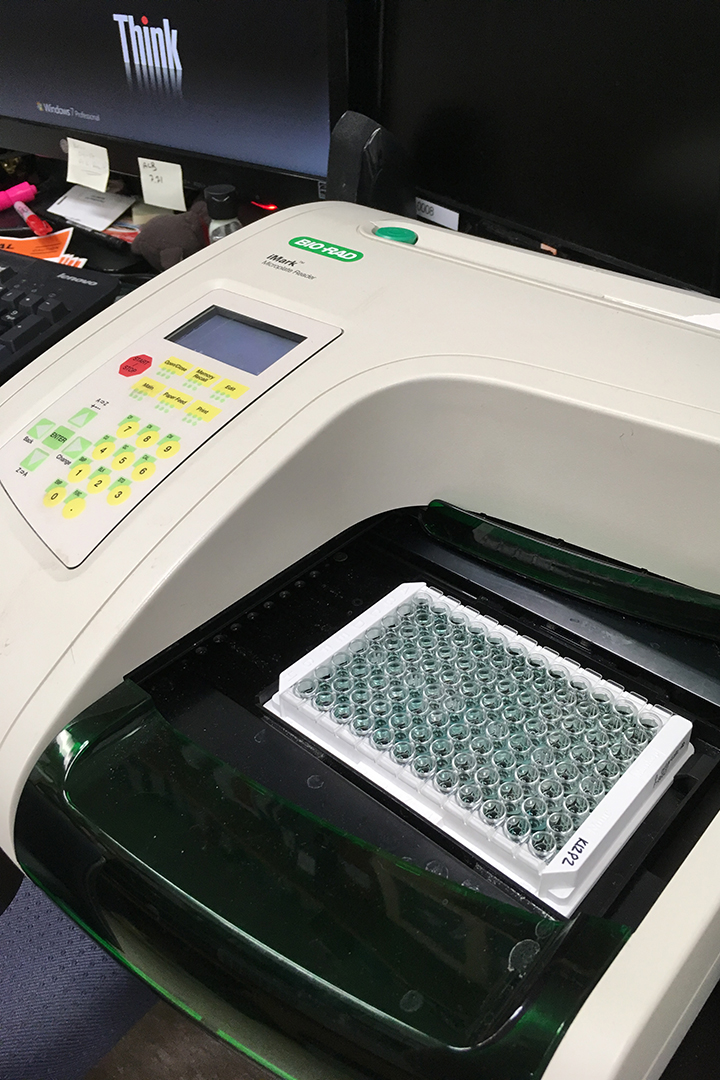

De Seram explains that the advantage of the saliva test is that it’s based on the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This means the antigen, or parts of the parasite, are put on the bottom of a plate and then saliva from the animal is added. If antibodies are present in the saliva, the researchers can measure the reaction.

Since this may be a more sensitive method compared to fecal egg counts, it may more accurately detect internal parasites, even at low levels. Using this test, researchers can also process a greater number of samples with less variability between laboratories.

“I really see the value and credibility of this particular research where it is aimed at product and method development,” says Sam Ekanayake, a WCVM research technician who assisted in the sample collection process.

“Farmers may not be comfortable with collecting feces because one thing is that it is a bit invasive — you have to put your hand in the [cow’s] rectum. So in that way, it’s not very appealing,” says Ekanayake.

In contrast, the collection of saliva from cattle is an easy, economical and practical alternative. Cattle producers could collect saliva samples using simple materials such as cotton swabs, and they could submit the saliva samples to the laboratory themselves.

Ekanayake acknowledges that collecting saliva can be tedious if it’s not done properly, and for safety reasons, it’s important to restrain the animal well. But in general, he considers collecting saliva to be an easier method.

In addition to detecting internal parasites, the saliva test may be useful in the future for other reasons, such as a genetic screening marker or for vaccine development.

Courtney Orsen of Hanley, Sask., is a second-year veterinary student at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM). Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.