Understanding X-rays can save dollars and lives

Dr. Jiaying Ng’s interest in the topic of gas in the abdomen began when she helped care for a canine patient that developed this potentially serious issue three weeks after surgery to remove a foreign body.

By Samantha Bray“We were uncertain whether this gas was due to persistence from previous surgery or perforation of bowel from a suspected foreign body,” says Ng, a veterinary surgical resident at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).

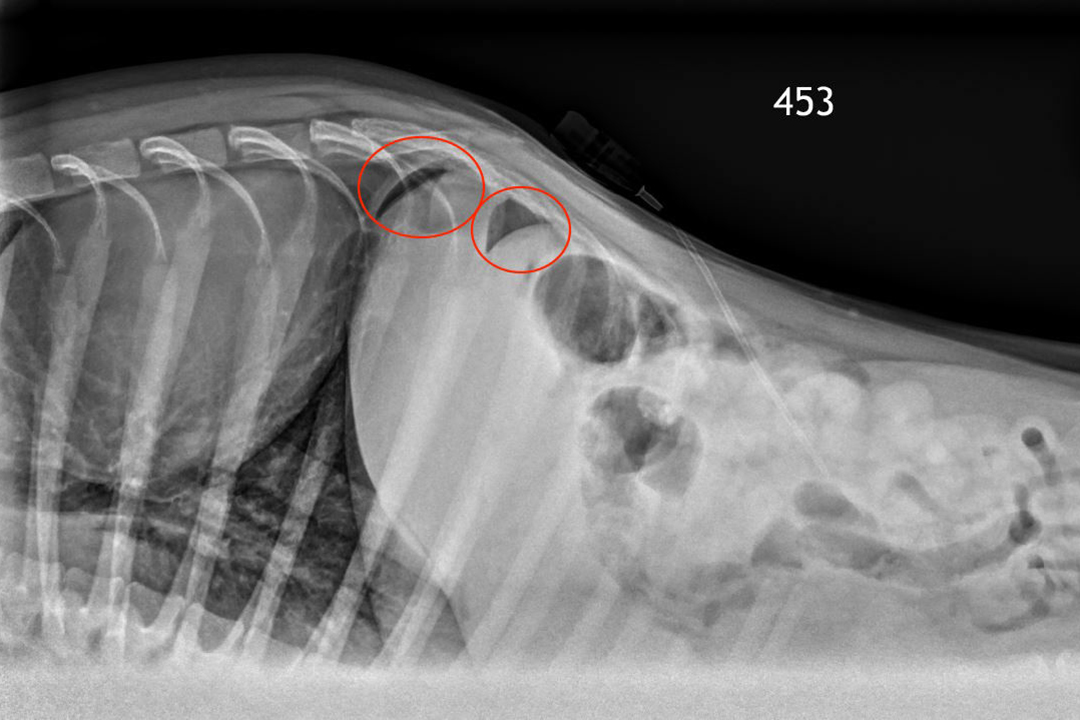

She’s now conducting research that focuses on pneumoperitoneum, or gas in the abdomen. Her study is to determine which radiographic view is most reliable to detect air in a dog’s abdomen.

While gas in the abdomen can be a normal phenomenon that may result from abdominal surgery, the condition can also be caused by a rupture in the stomach, intestines or any hollow internal organ such as the bladder — a situation that can be life threatening and require surgical intervention.

Dr. Kathleen Linn, a board-certified veterinary surgeon and associate professor in small animal surgery at the WCVM, recalls the case.

“When we took X-rays, we didn't see strong evidence of an obstruction. What we did see, though, was a lot of air in his abdomen,” says Linn.

As she explains, free air in the abdomen (not contained within an intestine) must come from somewhere. In most cases when veterinarians see air on abdominal X-rays, it’s an absolute indication for surgery, since it implies a life-threatening intestinal leak.

“But this dog had had surgery three weeks before, and surgery lets air into the abdomen. The question was how long does air remain there after surgery? We didn't know.”

The WCVM team’s questions about the case led them to do exploratory laparotomy as a precaution—and no intestinal leakage was found. While the clinicians and surgeons did what was necessary for their patient in this situation, Linn believes research could have helped them make a more informed decision.

“No surgeon likes to do an operation that turns out to be unneeded: it incurs added risks, costs, and recovery time for the patient,” says Linn.

She adds that the case was particularly frustrating because if X-rays hadn’t shown that the dog had air present in his abdomen, the clinical team would have opted for medical treatment versus surgery.

“We did put a dog through a surgery that was unnecessary. However, the risks of not doing surgery and sitting on a brewing septic peritonitis from [a] perforated bowel far outweighs the morbidity from a negative explore,” says Ng. “It would have been good to have a clearer idea of the duration of post-operative pneumoperitoneum which might have helped with decision making.”

While X-rays can detect small amounts of air in the abdomen, they can be a challenge to interpret because of air present in overlapping intestines. In her study, Ng and her team members are sedating clinically normal dogs and then using local anesthetic before placing a catheter in each animal’s abdomen so they can make multiple injections of air.

After the dogs are radiographed in different positions with varying amounts of injected air, board-certified radiologists at the WCVM are interpreting the X-ray images. The specialists are “blinded,” meaning that they don’t know which images are of normal dogs and animals that had air artificially introduced into their abdomens. After all of the radiographs are graded by the imaging specialists, the data will then be statistically analyzed to determine which X-ray view is most sensitive and reliable in detecting the presence of air in the abdomen.

That information will help will help with the second part of the project where the research team will use the most sensitive radiograph view to determine how long post-operative gas normally stays in a dog’s abdomen. With these findings, the researchers hope to create a standardized protocol that clinicians and surgeons can use to identify and track true cases of pneumoperitoneum in dogs.

This information could help to avoid another major operation to diagnose the problem.

“We are hoping that this research will help to give surgeons some guidelines for how long they can reasonably expect to see air in the abdomen after surgery,” says Linn. “Such information should help people decide whether pneumoperitoneum in a postoperative patient is more likely due to previous surgery or to a new problem.”

Results from this study could also have huge implications for pet owners. If clinicians can provide their clients with an effective and minimally invasive alternative to surgery, that will mitigate some of the additional risks and cost associated with the more traditional treatment for gas in the abdomen.

“Time is of the essence when it comes to treating cases of perforated organs in the abdomen. If we can identify these cases quickly and start treatment as soon as possible, it may increase survival time and decrease hospitalization time,” says Ng. “That could potentially save clients hundreds to thousands [of dollars] in terms of treatment and hospitalization duration.”

Samantha Bray of Winnipeg, Man., is a second-year veterinary student who was part of the WCVM’s Undergraduate Summer Research and Leadership program in 2017. Samantha’s story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.

Visit cahfpets.ca to read the latest news stories in Vet Topics (Winter 2018), news publication for the WCVM Companion Animal Health Fund.