Let the kisses spread love, not worms

If your dog enjoys a meal of raw organs and considers feces a delicacy, you may want to rethink trading kisses with them – and not just because of bad breath and bad bacteria.

By Joy WuEchinococcus spp. (E.multilocularis and E. canadensis) are zoonotic parasites spread in the feces of infected wild carnivores such as coyotes, foxes and wolves. Domestic dogs can also be infected. Although the parasite generally causes no problems in these animals (which are considered the definitive hosts), it can cause problems in other animals and people – and most recently, dogs.

“We are seeing a lot more cases in dogs in Saskatchewan where they are serving as the intermediate host for E. multilocularis,” says. Brent Wagner, a departmental assistant in the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s (WCVM) Department of Veterinary Microbiology. “One reason there may be an increased number of cases in dogs recently could be due to more infected coyotes in the area.”

Because exposure to Echinococcus spp. tapeworms can cause serious health problems for humans, this recent increase in the number of dogs being exposed to the parasite is concerning to scientists at the WCVM.

During the summer of 2018, in a study led by Wagner and Dr. Emily Jenkins, an associate professor in the Department of Veterinary Microbiology, researchers set out to determine the prevalence of Echinococcus spp. tapeworms in Saskatchewan’s coyote population.

Once a coyote is infected, it begins shedding eggs in its feces as early as four weeks for E. multilocularis, or six to seven weeks for E. canadensis. The parasite’s life cycle continues when herbivores ingest the eggs in the carnivore feces; either rodents for E. multilocularis, or cervids (members of the deer family) for E. canadensis. Humans who accidentally ingest the eggs or segments of the worm that contain the eggs can face severe health consequences.

One species of this tapeworm, E. canadensis, “leads to the formation of a space-occupying cyst in various organs including the lung, liver and brain,” explains Wagner. “The organs’ functions are then compromised. The cyst can be the size of a dime or as big as a basketball.”

The other species, E. multilocularis, can be even more serious, behaving like a parasitic tumour originating in the liver of the person. However, this is a rare disease and thus far only one human case has been detected that was thought to be locally acquired in Saskatchewan.

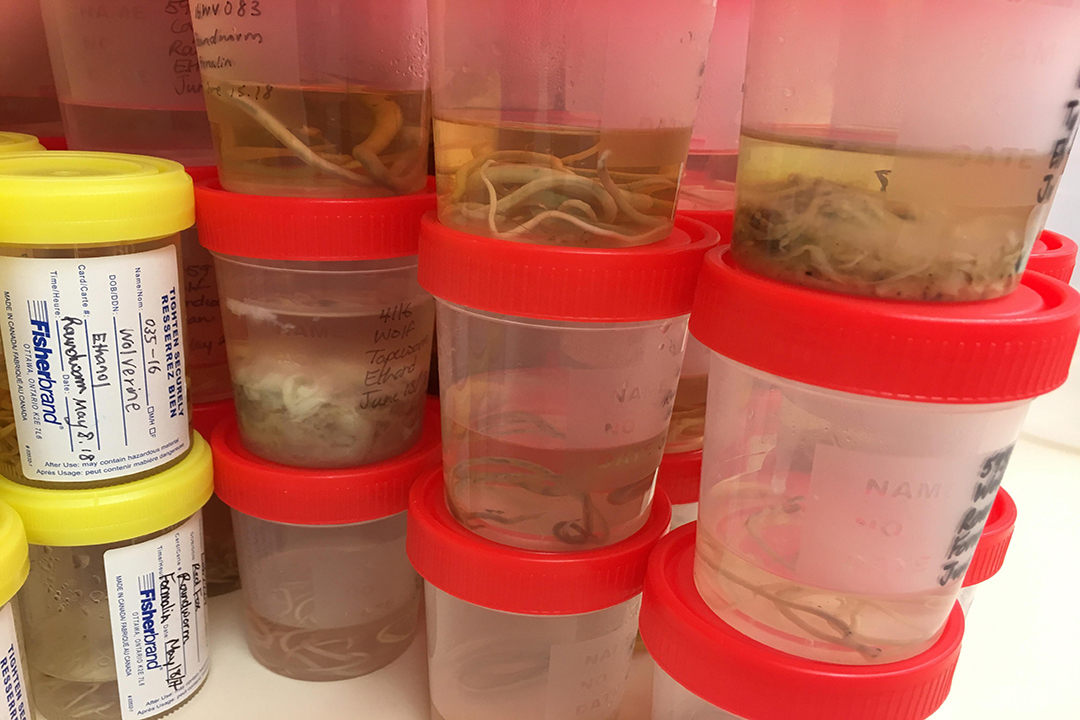

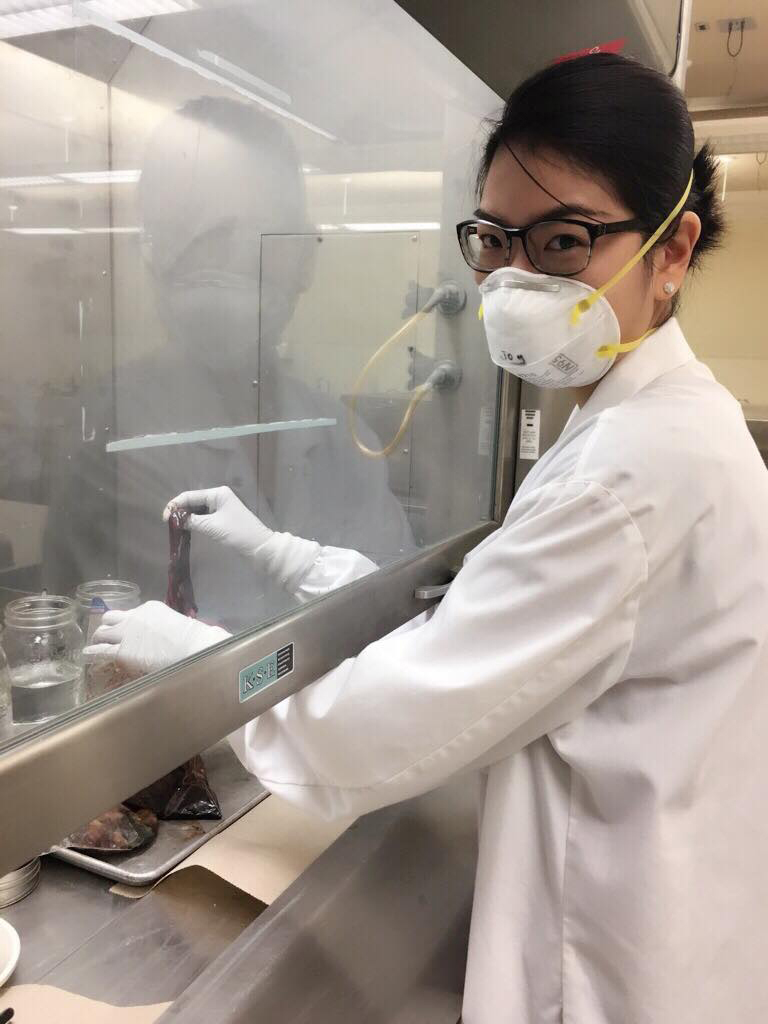

Currently the most accurate method for detecting the parasites involves examining the intestinal contents of deceased animals. Using 210 coyote cadavers submitted by Saskatchewan trappers, the WCVM researchers examined their intestinal contents under a microscope and counted the number of adult worms in each sample.

The researchers also conducted the current test fecal egg count test generally done in veterinary practice and a new fecal DNA test that promises to provide a convenient, accurate alternative for detecting Echinococcus spp. and other tapeworms. The sensitivity of the fecal egg count was low, detecting less than a third of the truly infected animals, while the DNA test showed promising results, detecting at least 80 per cent. However, this test only tells us if tapeworms are present, not which species.

“This study not only estimated the prevalence of Echinococcus in the Saskatchewan coyote population, but also tells us how good this new DNA test is versus finding the eggs in fecal sample or collecting adults from the intestine,” explains Mila Bassil, a summer research student who has participated in other research projects investigating parasites.

More than 70 per cent of the coyotes were infected with the tapeworm, and all examined so far have proved to be E. multilocularis, the more pathogenic of the two species. Previous studies have estimated that 20 to 30 per cent of coyotes in western Canada harbour the parasite.

Since fecal samples are much easier to collect, and surveillance for this parasite in urban environments is one of the great ways to prevent it from spreading, the researchers are optimistic that the new tapeworm DNA test will provide an important mechanism for protecting both animals and humans.

The Jenkins lab, including graduate student Temitope Kolapo, is working with Dr. Caroline Frey, research scientist at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency Centre for Food borne and Animal Parasitology, on a DNA-based test that will be sensitive as well as specific for Echinococcus spp.

“If the fecal DNA test proves to be reliable, it can be used to screen high-risk dogs and be a great tool that will help veterinarians in preventing public health problems,” says Wagner.

Joy Wu is a third-year veterinary student at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine. She is originally from British Columbia. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.