Understanding the patterns of superbug resistance in dogs

Even if your dog is perfectly healthy, there’s a chance that it could be at risk of developing an infection caused by bacteria with superbug bacteria – and treatment options are decreasing.

By Cayla PinheiroThe term superbug refers to any bacteria or microbes that have developed antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – the ability to grow in the presence of a drug that would normally kill them or prevent their growth.

Unfortunately, the emergence of AMR pathogens is outpacing the development of effective treatment options as they rapidly develop the ability to resist many of the drugs now available – particularly since many of the most recent antimicrobial drugs are just slightly modified versions of previous ones that had already lost their effectiveness.

“We can’t treat our patients with drugs that we used to be able to use,” says Dr. Joe Rubin, an associate professor at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM). “We’re starting to get to a time where we may have untreatable infections because there simply aren’t new compounds available.”

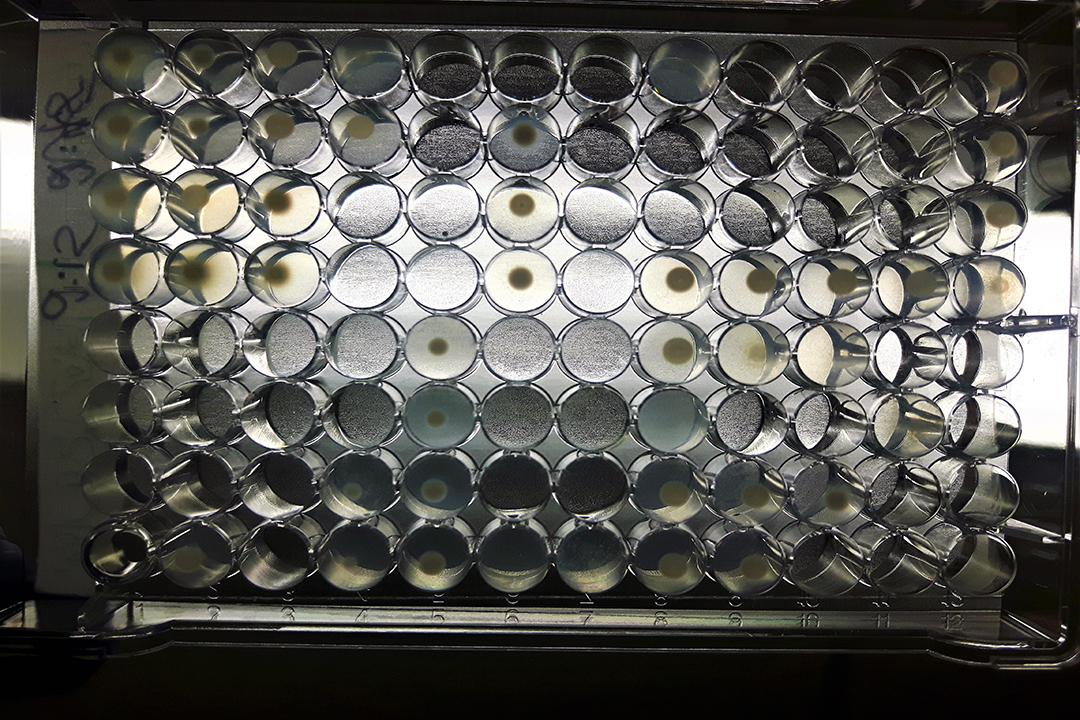

Rubin and a team of researchers from the WCVM’s Department of Microbiology are investigating the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in samples collected from dogs infected with specific gram-negative bacteria called Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Their goal is to determine whether commonly used antibiotics are effective at killing or stopping the growth of these bacteria.

“It [Pseudomonas aeruginosa] is an organism that is notoriously resistant so it’s really difficult to treat,” says Rubin. “It is intrinsically resistant to many drugs, so there are a lot of compounds that we just can’t use on even really susceptible P. aeruginosa – they’re just naturally resistant.”

Opportunistic infection by P. aeruginosa often occurs in human and animal patients that are hospitalized for an extended period, particularly if they have a weakened immune system or are being treated with antimicrobial drugs for a specific condition.

For example, human patients suffering from cystic fibrosis undergo several rounds of antimicrobial therapy treatments, and the combination of repeated antimicrobial use with compromised immune function creates the perfect environment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

In dogs, P. aeruginosa is most commonly isolated from ear infections. These infections are almost always secondary to pre-existing conditions such as endocrine disorders or food allergies that make the animal more susceptible to infection. Once the dog is treated with antimicrobials, P. aeruginosa bacteria are able to enter and set up shop.

While cases of P. aeruginosa infections have historically been opportunistic infections, current research indicates that community-acquired resistance is becoming more and more common – that means healthy, untreated patients are now susceptible to the bacteria.

“It all comes down to evolution and adaptation,” explains Rubin. “Normally, resistant organisms are thought to originate in hospitals and long-term care facilities, places in which there is a lot of antimicrobial use. But bacterial evolution and adaptation are occurring at a population level, and the animals that haven’t previously been treated are getting caught in the crossfire.”

As the incidence of AMR increases, your healthy pets face a greater risk of developing resistant infections that are hard to treat, and it’s critical that practitioners know which therapies are effective against them.

Since there is little evidence guiding treatment options for cases of infection with P. aeruginosa, the researchers hope this study will ensure that clinicians have the necessary information to select the appropriate antimicrobial therapy rather than use a best-guess approach for treatment.

Cayla Pinheiro is a second-year veterinary student at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.