Shining a new light on old cases: looking to the past to improve cancer care

When an eight-year-old Labrador retriever named Ruby was brought to the Veterinary Medical Centre (VMC) at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) in 2016, her owner reported symptoms that had started with the loss of sensation in her back legs, followed by the loss of bladder control and eventually her ability to walk.

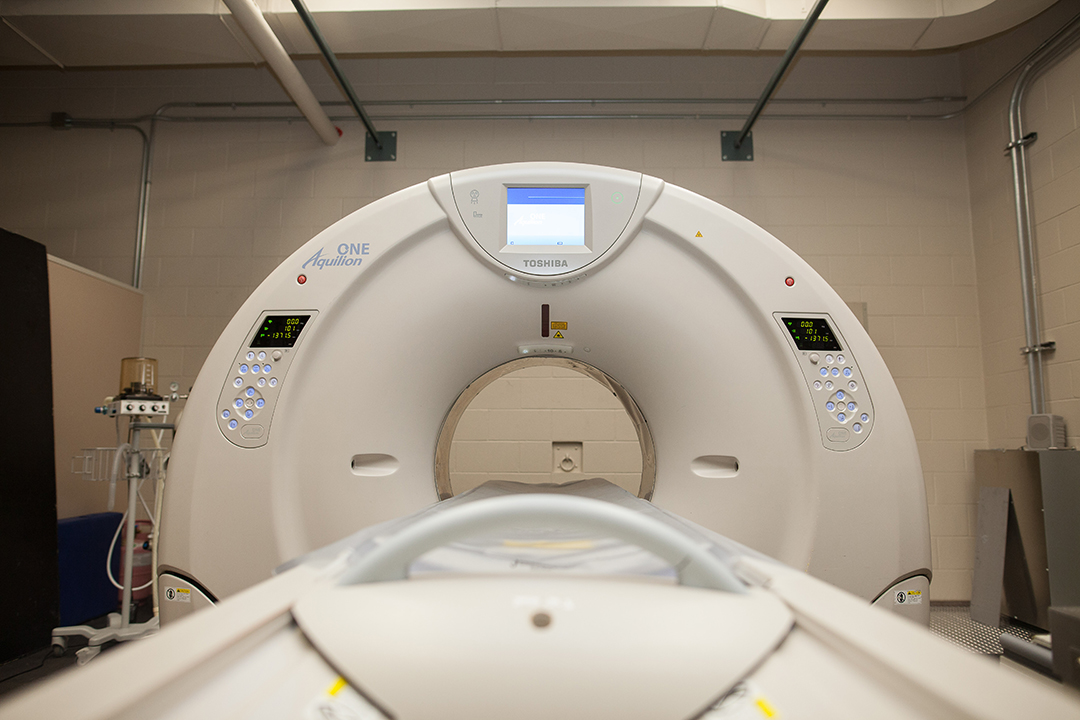

By Kimberly WilliamsSuspecting that a tumour was compressing Ruby’s spine, the VMC clinicians investigated by performing a computed tomography (CT) scan of her abdomen and pelvis. Although CT scans can often provide clear pictures of cancerous growths, the results in this case were disappointing and provided little information about the specific characteristics of the cancerous region.

Unfortunately, that’s a common issue for veterinary oncologists. For Ruby and countless other patients suspected of having cancer in the hind end, it’s often difficult to determine the severity of their cancer based on the results of a CT scan. It’s particularly difficult to determine whether the cancer has metastasized to the nearest lymph nodes.

To combat this diagnostic limitation, a team of researchers from the WCVM has been analyzing CT scans from previous cancer patients with the goal of developing guidelines that clearly define the radiologic features of normal lymph nodes in canine patients.

“The reason [the lymph nodes] are so important is because even if we treat a primary tumour and cure it, if we leave behind a node with disease in it, that patient could die of metastasis from that node,” explains Dr. Monique Mayer, a veterinary radiation oncologist at the WCVM. “That really underlines why its so important to know why a node is cancerous or not.”

Mayer and her research team are analyzing specific abdominal lymph nodes in 200 patients, including 100 patients from the VMC and 100 from the Veterinary Teaching Hospital at Colorado State University.

By recruiting such a large group of patients, the scientists can examine a wide variety of images and develop guidelines tailored to the diverse sizes of the patients that veterinary oncologists encounter.

Lymph nodes are small clusters of tissue found throughout the body. Since the local lymph nodes are often the first site affected by a cancer that’s spreading, they play a significant role in cancer metastasis.

The guidelines that veterinary radiologists use to assess lymph nodes for metastasis are based on protocols established for use in human patients, and there’s little data available from canine cancer cases.

Unlike humans, dogs are a diverse species in terms of their size, and previous work has shown that lymph node size is correlated to the size of the dog. The size is also influenced by the status of the disease.

Ideally, a lymph node can also be aspirated — a procedure in which a needle is used to extract cells for testing. However, this procedure is difficult to carry out in the hind body where the major lymphatic center is largely enclosed by the bones of the pelvis.

“It’s always a question: is this lymph node enlarged?” Mayer says, recounting the common dilemma she has faced in past cases. “I would be faced with patients where aspiration couldn’t give me the answer I needed, and I had to rely heavily on the imaging [when deciding how to treat], but without accurate guidelines to work with.”

Once their work is completed, Mayer and her team aim to implement their findings into clinical planning for VMC canine cancer patients.

“Our goal is to provide more accurate guidelines for oncologists to aid in clinical decision making,” says Mayer.

With improved guidelines in place, oncologists at the VMC and other centres will be able to provide more accurate prognoses and treatment plans that are better suited to the specific stage of cancer.

Once veterinary oncologists can ensure that cancer treatment targets only the affected areas and provide complete treatment to areas that would have otherwise may have been missed, they’ll be able to provide more effective and affordable care to canine cancer patients.

“I’ve lost three dogs to cancer, so I am happy to see research being done to detect it better,” says Ruby’s owner, who prefers to remain anonymous. “I would have liked more time with them, so I’m glad that information from Ruby’s case can help provide that for other families.”

Kimberly Williams recently completed her second year of veterinary studies at the WCVM. She is originally from Okotoks, Alta. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.