First veterinary class celebrates 50 years

Drs. Ernie Olfert and Peter Rempel were working at a fishing camp at Dore Lake, Sask., in 1965 when they received the letters that would change their lives.

By Jeanette NeufeldThe lifelong friends celebrated their acceptance as members of the first class at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) — the new regional veterinary college for the four western provinces.

Both men had wanted to become veterinarians for years — but admission into Ontario Veterinary College, Canada’s only veterinary college at the time, was nearly impossible for western Canadian students. Rempel first worked as a teacher and Olfert took pre-medical studies as they waited for the new veterinary college to open on the University of Saskatchewan (USask) campus.

That day finally came in 1965 when the WCVM’s Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) program became available to students from Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Alberta and British Columbia.

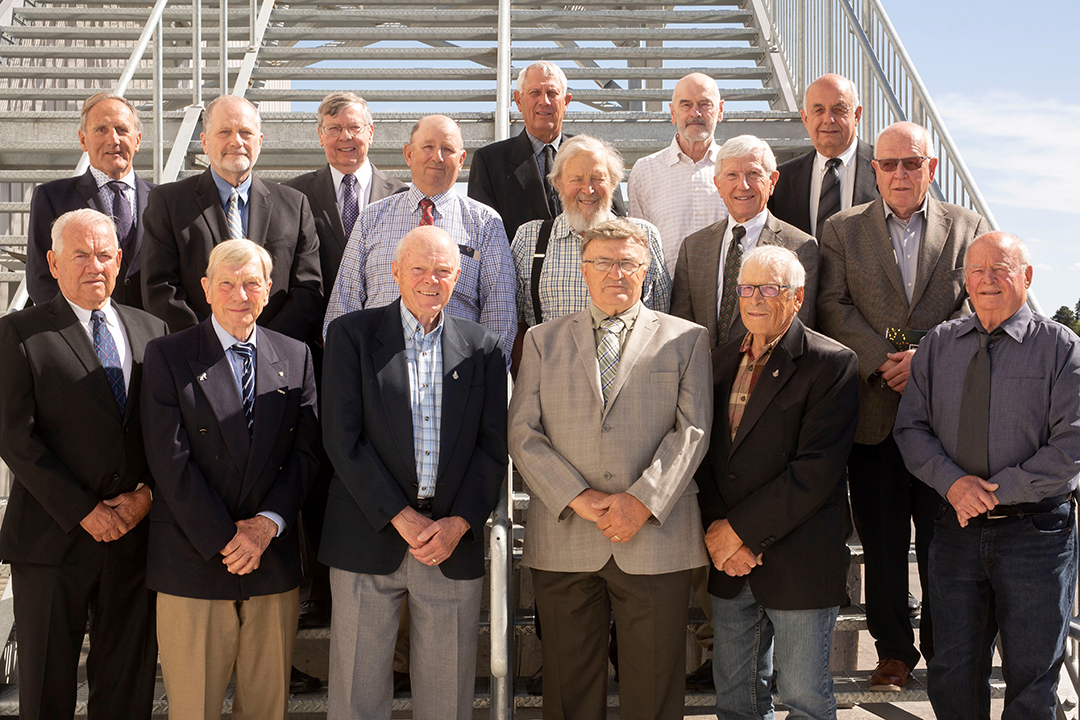

This spring, members of the WCVM Class of 1969 celebrated the 50th anniversary of their graduation with a class reunion. The veterinary alumni were special guests at this spring’s USask convocation ceremonies and participated in the WCVM evening awards banquet where the Class of 2019 — members of the college’s 50th class — celebrated their own graduation.

Being part of the WCVM’s first class wasn’t easy. Since their courses were spread across campus while the new college was under construction, Rempel and Olfert remember trudging through construction zones with only 10 minutes to spare between classes.

Several classmates — Ed Wiebe, Don Jamieson and Rempel — lived at the veterinary college once it was built, taking emergency calls in the veterinary clinic at night.

It was a rigorous program, one that gave them a lot of hands-on experience.

“In the vet college, if you dawdled at all you were so far behind you couldn’t catch up,” says Rempel.

“It was a hard four years, but it was worth it,” recalls Olfert, who recalled the more proficient note-takers sharing their work with the others.

The students were also learning alongside their professors. In the 1960s, advanced veterinary training was still difficult to access, and many of these fledgling professors were also learning how to teach.

WCVM’s first veterinary graduates entered a rapidly changing profession.

At first, clients expected their large animal veterinarian to be something of a cowboy.

“If you went into large animal practice, you did a lot of work at the end of a rope. Farmers still expected you to be able to rope and catch that animal, as well as treat it,” says Rempel, who entered practice in Unity, Sask.

In the 1970s, attitudes toward dogs, cats and other companion animals began to change. While most graduates initially entered large animal practice to meet the demand of Western Canada’s agriculture industry, a few veterinarians set up shop in cities, serving a growing small animal clientele. Initially, the most money could be made in equine medicine, but this quickly shifted to pets.

“I probably hadn’t seen more than two cats until about 1971, then suddenly, cats started coming in,” says Rempel, whose small animal caseload grew to about 25 per cent by the mid-1970s.

The increasing number of female veterinarians has been another major change in the profession. The Class of 1969 was the WCVM’s first and only class with no female graduates. Fifty years later, only 13 of the 78 graduates in the Class of 2019 are men.

Much like it is today, the WCVM’s first graduates were in high demand. Many of the 1969 graduates didn’t attend their own convocation ceremonies because they were already busy working, filling the desperate need for veterinarians across Western Canada.

“In 1969, if you called five places, you could have got five jobs,” Rempel says.

Olfert had a similar experience, receiving a job offer on the spot at the second veterinary clinic he visited. He recalls being asked if he could start the next day: “I hadn’t even graduated yet.”

Members of the first class went on to serve varied careers, including roles in large animal and small animal medicine, equine medicine, pathology, reproduction, regulatory medicine, human medical research and education, and public service. Rempel eventually left private practice to serve as Saskatchewan’s provincial veterinarian while classmate Dr. Terry Church filled a similar role in Alberta.

Olfert became USask’s longtime university veterinarian and helped set up national regulations for protecting the health and welfare of research animals that have become a model for the humane treatment of lab animals worldwide.

“When I started, there really weren’t any government or national standards. In a sense, that all got built, and I was a part of that,” he says. “Now there are very high standards of regulation, 50 years later.”

Olfert also served as president of the Saskatchewan Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SSPCA) and was instrumental in the development of a program for handling rural farm animal welfare concerns and complaints through regional peace officers.

The first WCVM class began their philanthropic efforts by establishing the college’s first class fund, raising money for the expansion of the WCVM’s veterinary teaching hospital (now the Veterinary Medical Centre), research awards, and the annual WCVM ’69 Class President Award. Since 2004, 15 students have received the $2,000 award in recognition of their contributions to the college and student life.

“If you want to look at all of us, veterinary medicine was our whole lives. For me as a large animal practitioner, it was 24 hours a day,” says Rempel. “Cumulatively, the feeling came across that maybe we should support new veterinarians, tell them what a good thing it is.”