Getting objective insight into your pet’s vision

Imagine this: you notice that your dog is bumping into corners and objects, and you begin to suspect that he’s starting to lose his sight.

By Stephanie ChangBut when you seek more information, what if your veterinarian told you that the current methods of assessing vision in companion animals are all subjective and inaccurate?

Dr. Danielle Zwueste, a small animal neurologist at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), is leading a team of researchers to potentially change this fact.

"Right now, we can only rely on methods such as behavioural observations, evaluating reflexes, and a patient’s ability to track falling cotton balls for functional assessment of the visual pathway,” says Zwueste. “But oftentimes, it’s all just an educated guessing game.”

The WCVM research team is investigating the potential use of visual evoked potentials (VEPs) in veterinary medicine as a more accurate and reliable method for vision evaluation. VEPs are brainwaves measured from the occipital lobe — the portion of the brain at the back of the skull where the vision centre is found — which are representative of visual function.

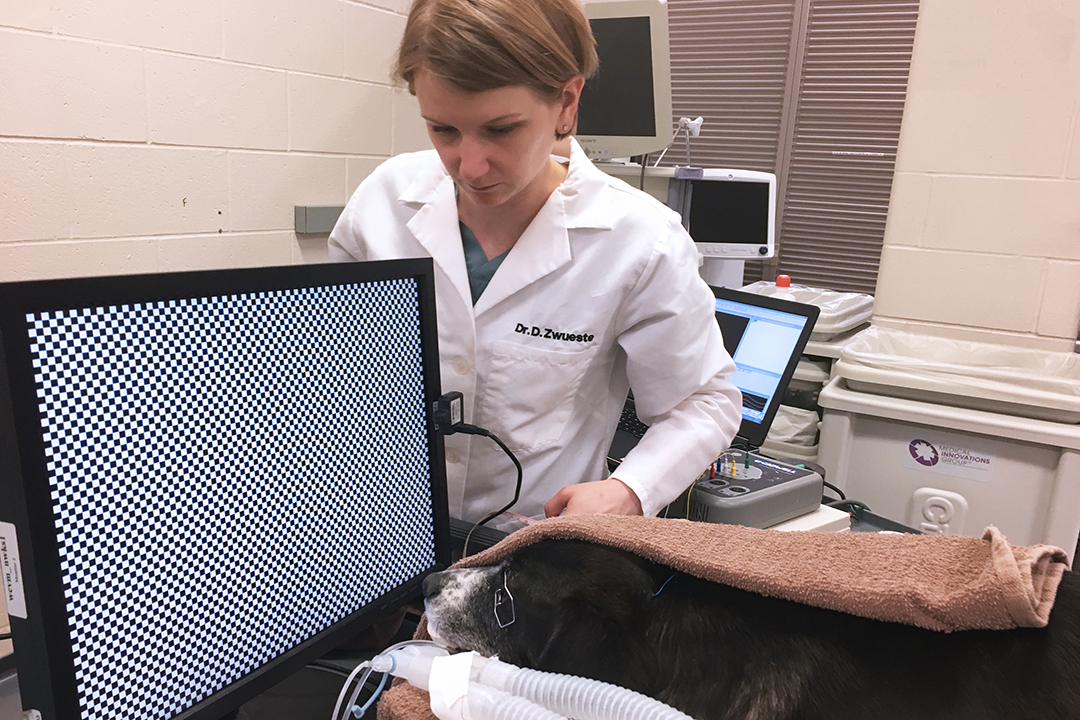

To measure VEPs in a dog, several skin electrodes are placed in the scalp between the animal’s eyes and at the back of the skull. When a stimulus is shone into the dog’s eye, the resulting waveforms are picked up by the electrodes and captured on the computer where they show up as several peaks and troughs.

Researchers can use different stimuli during the process. One is the pattern stimulus, which is an alternating black and white checkerboard that reverses its colours at a certain rate. Another is the flash stimulus, which is simply a flashing white light shone into the eye.

The clinical use of VEPs is quite widespread in human medicine as it is non-invasive, low cost, and objective. It’s been used to diagnose multiple sclerosis and associated symptoms such as asymptomatic inflammation of the optic nerves. VEPs can also detect subclinical lesions in the visual pathway that are otherwise poorly visualized by other diagnostic tools such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

In addition, VEPs have been valuable in assessing the visual system in infants — and the same principle can be applied to other non-speaking patients, such as dogs and other companion animals.

“Researchers have only begun to explore the use of VEPs in veterinary medicine in relatively recent times,” says Zwueste. “There are still many unanswered questions that must be addressed before VEPs can be reliably used in a veterinary clinical setting.”

The process of measuring VEPs requires multiple recordings, and the patient needs to stay still while the eye receives the visual stimulus. That means clinicians need to put dogs and other companion animals under sedation or general anesthesia when recording VEPs since even the most well-trained dog can’t stay still for that long.

However, there’s a problem: drugs used for sedation and anesthesia can depress the brain’s activity and alter the appearance of the VEP waveforms. So far, there are only a few published research studies investigating the effects of anesthetic agents on VEPs.

“This is why we are looking more into how commonly-used sedation and anesthesia protocols in veterinary medicine can affect the waveforms and comparing the two protocols to see if one is better than the other,” says Zwueste. “This is important and necessary before we can begin implementing VEPs as a common clinical diagnostic.”

By understanding how common clinical practices such as anesthesia and sedation affect VEPs, veterinarians are closer to developing a standard for using VEPs as a diagnostic tool in a clinical setting. The researchers’ hope is that it can provide an objective and accurate assessment of vision loss in animals — which can be the result of a multitude of diseases.

“Using VEPs can allow veterinarians to better monitor disease progression and the animal’s response to treatment,” says Zwueste, “and most importantly, they can provide more information about the pet’s health and wellbeing that pet owners seek from veterinary professionals.”

Stephanie Chang of Vancouver, B.C., is a fourth-year veterinary student at the WCVM. Her research story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.