Playing ‘bee’ to study pesticide effects

Pretending to be a honey bee is a lot of work, but researchers at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) have proved they’re up for the challenge.

By Crystani Folkes

A team of researchers led by Dr. Sarah Wood from the WCVM’s Department of Veterinary Pathology set out to duplicate the conditions of a hive within their laboratory so they could gain insight into the impact of the various pesticides used in Saskatchewan on honey bee larvae.

Once they’ve studied the chemicals’ effects at both the colony and individual bee level, the researchers plan to correlate these changes with the doses of pesticides present in the Saskatchewan environment in order to establish guidelines for a safe dose range.

Honey bees are crucial pollinators, but they are regularly exposed to chemicals that threaten their survival. Reports indicate that approximately 60 per cent of the world’s honey bees have been lost since 2004 — and without honey bees, our entire food supply is at risk.

On the other hand, Saskatchewan is a fearless leader of agriculture. The province’s farmers grow crops that are used to feed the entire world, and pesticide use is a key factor in the success of the agricultural industry.

The WCVM researchers focused their study on the chemicals routinely used on Saskatchewan crops — chemicals that can be detected in the soil, water and even the pollen and nectar of the Saskatchewan landscape.

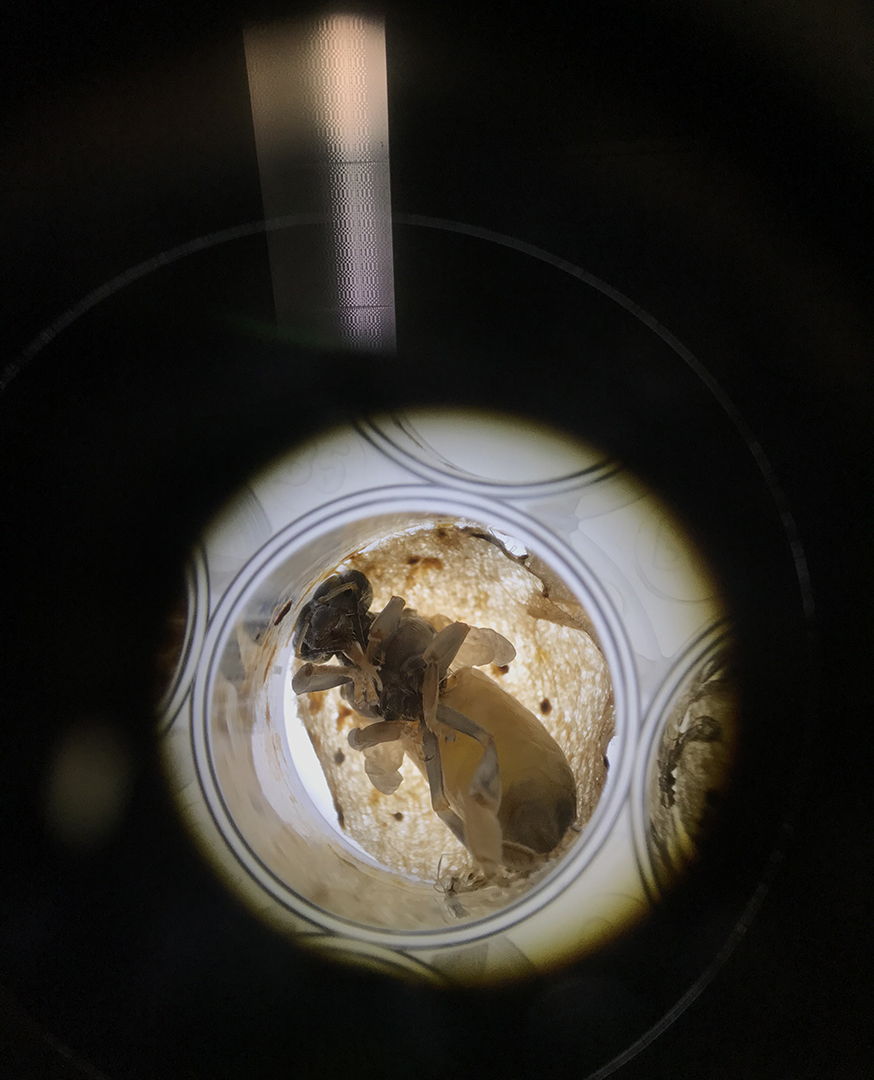

They began their simulation of the honey bee’s natural cycle just four days after they hatched from eggs by transferring the baby bees into special cups similar to the cells of a hive. The bees were then fed and monitored until they became adults.

“We’ve developed techniques to raise honey bee larvae in the lab and allow them to go through their 21 days of development and emerge as adults,” says Wood. “This allows us to expose them to pesticides in a controlled laboratory environment and see what the effects might be.”

To replicate natural conditons, the scientists had to pretend to be honey bees by visiting the larvae many times a day and keeping them safe, warm and clean. Throughout the larvae’s growth cycle, Wood and her team monitored their health as they were exposed to an assortment of chemicals through their diet.

“We have some understanding about what happens when adult bees are exposed to pesticides, but we don’t know as much about what happens when developing bees are exposed,” says Wood.

While this research is incredibly important within the scientific community, it also promises to provide key information for the beekeepers of Saskatchewan. Dr. Barry Brown, a veteran Saskatchewan beekeeper, explains that the study is essential to the welfare of Saskatchewan bees because it has a specific prairie flavour to it, and it takes into account the struggles and routines of the Saskatchewan beekeeper, specifically.

Although veterinarians have often been uninformed about the needs of beekeepers, Brown hopes to see a shift in the future. He points out that recent changes to antibiotic usage will require beekeepers to maintain a close relationship with their veterinarians to keep their hives healthy.

“The change is crucial and a long time coming,” says Brown. “I’m delighted that vet medicine is finally dealing with insects.”

Although bees have not been commonly considered within the realm of veterinary medicine, Wood and her team at the WCVM want to change that perception, and they believe that veterinarians and beekeepers can learn a great deal from each other.

It's a grim fact that honey bees have been in decline, but rather than throwing in the towel, Brown maintains the importance of rebuilding. He points out that’s simply the Saskatchewan mentality.

Brown also emphasizes that the beekeeping industry is incredibly important to the survival of bee populations and, therefore, the entire food supply. It's also important to establish a balance that enables the crops to be protected while the honey bees remain healthy.

“The only thing that’s keeping our bees going is the passion of the beekeeper,” says Brown.

Hopefully this passion, along with the findings of the WCVM study, will keep bees happy, healthy and pollinating for years to come.

Crystani Folkes is a member of the WCVM’s Class of 2021. She is originally from Lloydminster, Alta. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.