European foulbrood 'disease of opportunity'

Although pesticides are important for increasing crop production, they may be interfering with the immunity of an important animal pollinator — the honey bee.

By Jocelyne Chalifour

One particular study at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) has been investigating pesticides as a potential factor that increases the susceptibility of honey bees to European foulbrood (EFB) — a disease that has recently become more prevalent in North America.

While honey bee colonies can spontaneously recover from this disease on their own, EFB causes economic hardship for beekeepers, especially since it strikes in the spring just as many people in the industry are building up their colonies for the season.

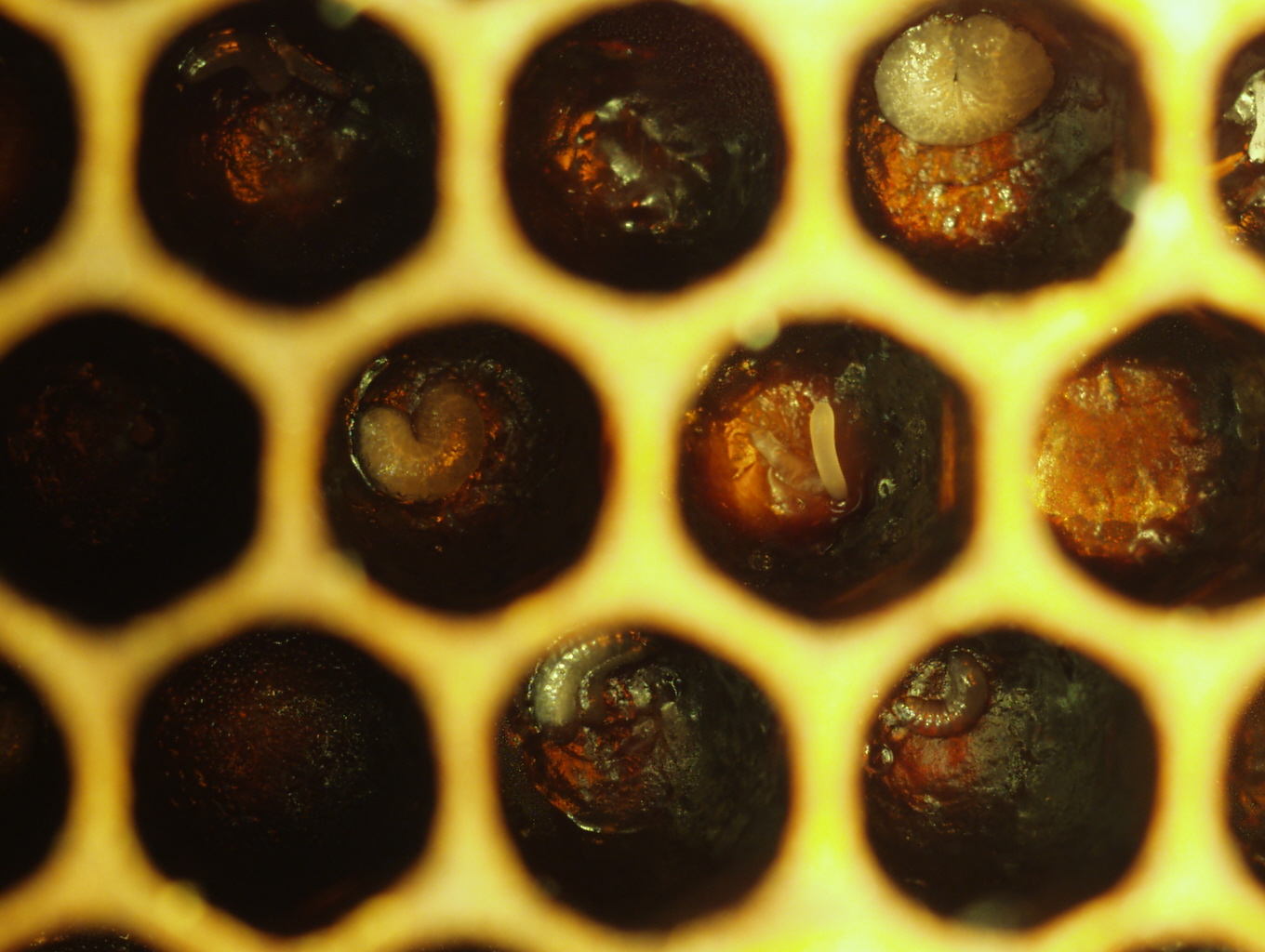

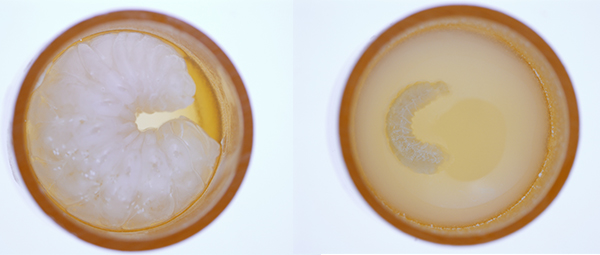

Caused by the bacterium Melissococcus plutonius, EFB infects the gut of the larvae (developing honey bees). The disease can out-compete the immature bees for food, resulting in their death — a phenomenon that can drastically weaken a colony.

“If you have a disease that is killing all of the young larvae, they’re not going to have enough bees later in the season to collect nectar and produce honey,” says Dr. Sarah Wood, a PhD student in the WCVM’s Department of Veterinary Pathology. “We’re interested to understand if pesticides can be a stressor that would predispose larvae to developing this disease.”

EFB is an opportunist, meaning that it tends to cause disease only when honey bees are under conditions of stress. Whenever the bacteria find a colony that is short on food or small or struggling for other reasons, it can gain a foothold and start killing the larvae.

Wood and her team are investigating pesticide exposure as one of the potential stressors responsible for the recent increased incidence of EFB in Canadian honey bee colonies.

Tim Wendell, a Saskatchewan beekeeper, experienced a relatively serious outbreak of EFB in his apiaries. He observed that yellow, twisted larvae — a typical sign of EFB —were more prevalent in the years following his decision to not feed oxytetracycline to all of the hives as a prophylactic cure for brood diseases.

“While we are unaware of the source of the EFB outbreak, we believe that it may have been prevalent in some of the replacement hives that we had purchased after a winter of heavy losses due to varroa mite (parasitic mite) problems,” says Wendell.

Testing confirmed the presence of EFB in Wendell’s hives, and the EFB seems to be occurring in an increasing amount several years after the purchase of these replacement hives.

“We suspect that we may have gotten some combs with EFB in it from the lower mainland in B.C., or possibly from some stock that we purchased in both Manitoba and Saskatchewan,” says Wendell. “But there is no scientific proof that it was brought in from outside our operation.”

He explains that combs are moved around a great deal during beehive maintenance, allowing the bacteria to spread quickly through colonies if it goes unnoticed.

“It seems to be [associated] specifically with some of the blueberry production. We’re suspicious of some of the fungicides that were sprayed, that it may be causing some stress and possibly the EFB.”

Since commercially-grown blueberries in Canada are commonly treated with a fungicide called boscalid, Wood and her research team incorporated this pesticide into their research.

Using specialized plates made specifically for worker bees, the researchers are growing honey bee larvae in the laboratory and feeding them a diet contaminated with a bacterial strain of EFB which was isolated from honey bee colonies pollinating B.C. blueberry crops. At the same time, the larvae are exposed to boscalid at concentration levels similar to those found in blueberry pollen.

By observing the larvae daily and determining their survival rate during the first week of development, Wood and her team will determine whether the fungicide is inducing stress and making the young bees more susceptible to EFB.

Honey bees play a crucial role as pollinators in the environment. Some plants rely solely on honey bees for pollination. These insects are also important in the agricultural industry as they increase crop yield and contribute to food security.

Now that commercial beekeepers are struggling with elevated levels of colony loss and disease, researchers are committed to discovering the reasons for their decline by investigating the effects of pesticides, climate change, habitat loss and diseases such as EFB.

While pesticide exposure in the environment, decreased antibiotic use and poor colony nutrition are some potential stressors that may be contributing to the prominence of EFB, future studies will focus on other possible explanations for outbreaks of the devastating disease.

“It used to be quite an uncommon disease, and now all of the sudden, we’re seeing it emerge. We want to understand why that is,” says Wood.

The WCVM team’s bee health research work, which is led by Dr. Elemir Simko of the college’s Department of Veterinary Pathology, has received funding support from a number of organizations including Project Apis m. and Costco Canada, Western Grains Research Foundation, Saskatchewan Canola Development Commission, Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund, Saskatchewan Beekeepers Development Commission, Alberta Beekeepers Commission, Canadian Honey Council, MITACS and ELAP (Emerging Leaders in the Americas Program).

View research article published in Insects (April 17, 2020).

Jocelyne Chalifour of Calgary, Alta., is a second-year veterinary student at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) whose summer research position was supported by the college’s Interprovincial Undergraduate Student Summer Research program. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.