Reversing the irreversible: a second chance with fertility

Veterinary researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) have recently unveiled a new field of study that’s focused on reversing and safeguarding against the loss of fertility in young males.

By Tim Cloutier

Fertility loss is a common issue in young cancer survivors, and the number of Canadian children diagnosed with cancer is increasing—especially among First Nations populations. Chemotherapy and other oncology treatments can cure different cancers, but they can also cause infertility in about 20 per cent of survivors.

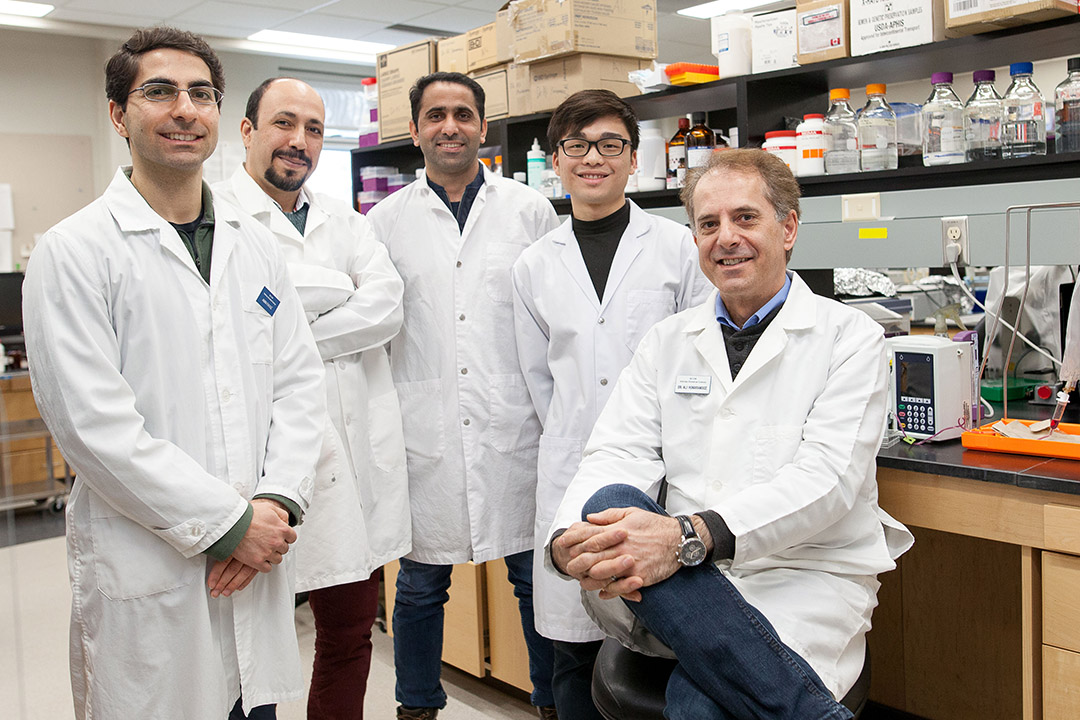

Led by reproductive biologist Dr. Ali Honaramooz (DVM, PhD) of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), the scientists are developing novel approaches to induce testis maturation. They aim to produce sperm in vitro (outside of a living organism) using biopsies from neonatal piglet testis as a model for restoring the fertility potential of young cancer survivors.

“This research will revolutionize many different fields of reproductive science and medicine,” said Honaramooz, a professor in the WCVM’s Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences.

“We predict that by using these models, we will be better equipped to study, manipulate and preserve spermatogenesis (sperm development) in humans. We now have the models required; it may not be long before we can preserve the fertility of pre-pubertal boys who must undergo cancer treatments.”

The WCVM scientists’ work recently led to a front cover image and article in the Feb. 2020 issue of Reproduction, Fertility and Development. The journal article stems from the WCVM team’s work in removing testes from piglets and then transplanting their cells into host mice. These transplanted cells regenerated testis tissue and triggered sperm cells to develop in the new hosts.

The complex process of spermatogenesis relies on many hormones, growth factors and various other signals that can drastically change the outcome under varying circumstances.

“Spermatogenesis is inherently difficult to replicate in vitro,” said Honaramooz, adding that various conditions must be ideal for in vitro spermatogenesis to occur.

“This includes proper proportion of cell types, their three-dimensional relationships and much more. The most difficult challenge has been to replicate the internal and external environment that the cells and tissues are exposed to in situ (in the body).”

Only a few other labs worldwide are conducting studies similar to Honaramooz and his research team. Since many fertility studies focus primarily on in vitro fertilization (IVF), the WCVM team is providing significant groundwork in in vitro spermatogenesis.

Using piglets as an animal model is a major advantage of the team’s research. Because pigs have more similarities to people than any of the lab species being used in other studies, the WCVM researchers have greater potential to unlock opportunities that benefit human medicine

Honaramooz and his team have already investigated the isolation and purification of pigs’ testicular tissue, as well as testis tissue grafting and cell injections. Their studies also promise to have a major impact on conserving endangered species.

The researchers are optimistic that their work will significantly improve quality of life for young cancer survivors by restoring their fertility.

“Given that this work is only being done in a small handful of labs, it is up to us to complete the groundwork necessary if any advancements in our field are to be made,” said Honaramooz.

“I think this is an exciting time. I feel a lot of the preliminary steps have been achieved and we are on to something big.”

The WCVM research team’s work is financially supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Tim Cloutier is a WCVM veterinary student who was part of the college’s Interprovincial Undergraduate Student Summer Research Program in 2019.