Fish give clues about oil contamination

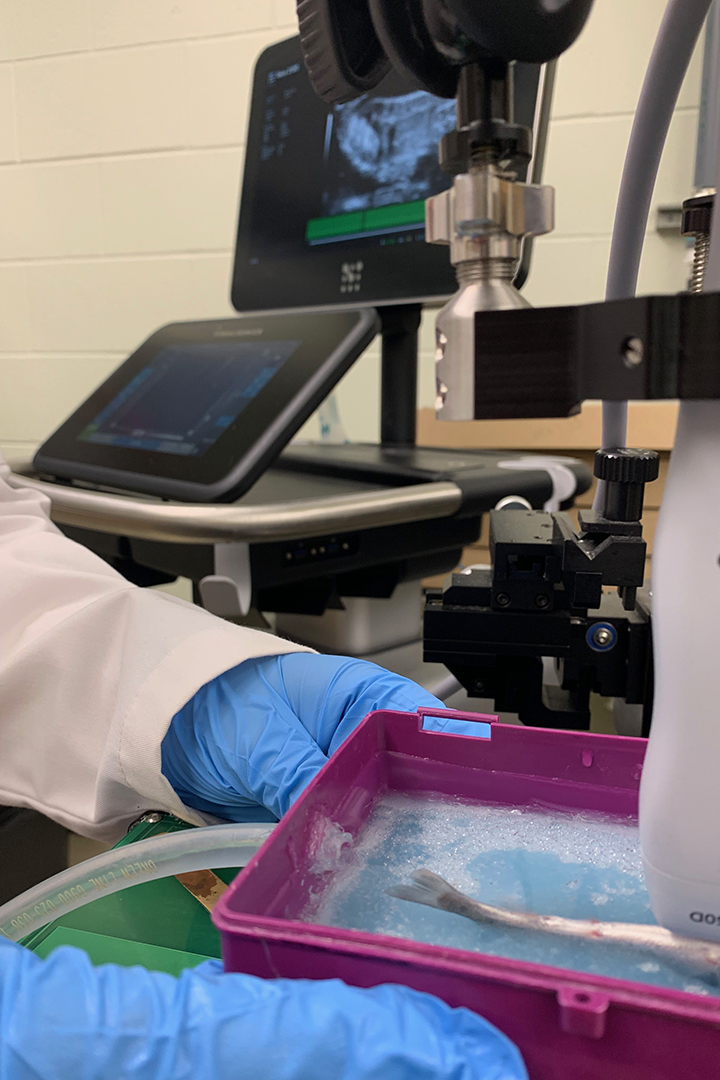

“Why do you ultrasound fish?” That question often came up while I conducted research at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) during the summer of 2019.

By Amy Taylor

My usual response was to explain that fish such as rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are a good sentinel species. They can help detect risks to people in the environment by providing advance notice of certain dangers.

Fish are often sensitive to changes in their environment, and an ultrasound machine has a high enough resolution to pick up these changes.

For example, oil pollution is known to have negative effects on the heart by affecting the organ’s muscle cells and the way the cells communicate to each other. This process can be detrimental to the heart because this massive muscle relies heavily on seamless communication throughout all the cardiac cells and a constant supply of oxygen and energy. The heart is also an important muscle in the body as it needs to constantly adapt to the ever-changing environment.

Contaminants such as crude oil are known to negatively affect the developing fish heart by causing swelling. Research has also suggested that compounds within crude oil may cause irregular heartbeats, or arrhythmias, by disrupting the heart’s electrical activity. Once arrhythmias develop, that individual is more prone to dying from this cardiac issue.

Research on the effects of oil spills is important for veterinary medicine as well as for human medicine. And as the demand for oil increases, the risk of oil spills occurring and exposure to oil is also increasing.

Led by Dr. Lynn Weber, a professor of physiology and toxicology at the WCVM, our research team studied the effects of contaminants such as crude oil on heart function and metabolism of fish.

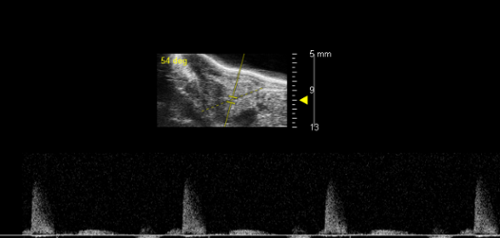

We used ultra-high resolution ultrasonography to distinguish normal versus abnormal cardiac function. We also used electrocardiography (ECG) to look for abnormal electrical activity, or arrhythmias, within the hearts of juvenile rainbow trout. Ultrasound imaging uses sound waves to produce pictures of particular areas in the body, while ECG measures the electrical activity in the heart.

“Virtually no one else in the world uses ultrasound to image fish hearts or ECG to measure electrical activity after they’ve been exposed to oil,” says Weber, adding that her team is using an ultrasound machine that produces high-resolution, high quality images.

“[Our machine] has a higher resolution than the best ultrasound machines used by human or veterinary cardiologists.”

Researchers exposed rainbow trout to crude oil for 48 hours and then used ultrasound imagery to determine if there was a change in heart function by looking at how much blood the heart pumped with each beat.

Fish are interesting to study compared to other animals because their exposure to oil is different than other species. Fish are exposed aqueously, which means the oil-contaminated water is in contact with their skin and gills. In addition, they’re also exposed orally to the water-oil mixture while they ingest food.

While the fish were under anesthesia, we used the high-resolution ultrasound machine to take snapshots of their hearts’ structure and function as well as simultaneously recording ECG. Researchers then analyzed short videos showing the beating hearts of fish and looked for irregularities in electrical activity.

Because the ultrasound and ECG machines are non-invasive, using them doesn’t change or alter how the fish’s entire body functions.

While compounds in oil may negatively affect the hearts of fish, researchers still need to determine the overall impact. For example, it may mean that exposed fish are less likely to handle different environmental stressors or have reduced reproductive success. The study’s results, which are still being analyzed, will have practical use for the environment and animal health.

The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) provided financial support for this research study.

Amy Taylor of Abbotsford, B.C., is a third-year veterinary student at the WCVM whose summer research position was supported by the Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars Program. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.