Scientists search for ‘pregnancy dipstick’ to predict labour

WCVM researchers are working to develop a test that could help give expectant mothers and their physicians more notice of an impending delivery.

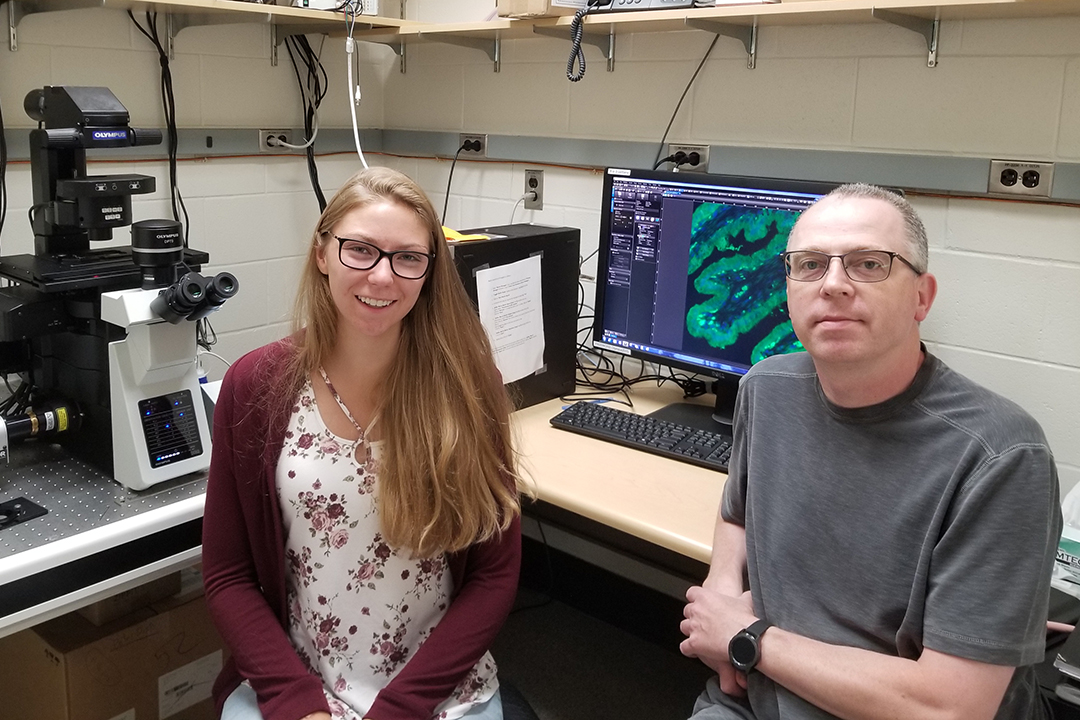

By Calista LytleWhile Dr. Daniel MacPhee left his previous faculty appointment at Memorial University of Newfoundland to join the Western College of Medicine (WCVM) faculty in 2012, the cross-country move to the University of Saskatchewan (USask) was still a homecoming of sorts for the reproductive scientist.

“USask has a long tradition — a very long tradition — of reproductive science research excellence,” explains MacPhee, an associate professor in the WCVM’s Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences.

As part of the One Reproductive Health Group at USask, MacPhee collaborates with scientists at the WCVM and from across campus, all of whom focus on reproductive biology.

“So by coming here, I have lots of colleagues that we can work with and collaborate with, and that makes for a richer experience.”

MacPhee and members of his research lab focus on how the uterine wall and placenta function and change during pregnancy. They’re working to develop a better understanding of the uterus during pregnancy by searching to identify potential markers that would more accurately indicate the approach of labour.

A delivery that occurs earlier than 37 weeks of gestation is described as a pre-term birth. In Canada, about eight per cent of all deliveries are pre-term births, and these account for about two-thirds of infant deaths.

While there may be some indicators that labour is approaching, there are no reliable signs or markers that can accurately predict when the onset of labour is imminent.

The myometrium is the smooth muscle component of the uterus that’s central to the labour process. MacPhee’s aim is to understand the factors causing the specific changes to the myometrium throughout the pregnancy with the goal of identifying markers that signal labour.

“My dream would be that we understand enough about labour in the next five to 10 years that it becomes a lot more viable for us to develop true strategies to accurately and quickly predict it,” says MacPhee.

For example, MacPhee describes a future test that would work as a blood marker or “pregnancy dipstick,” giving expectant mothers and their physicians more notice of an impending delivery.

A Saskatchewan example

While this information would benefit all pregnant women, it’s critical for expectant mothers living in rural communities who must travel several hours to reach the nearest birthing centre.

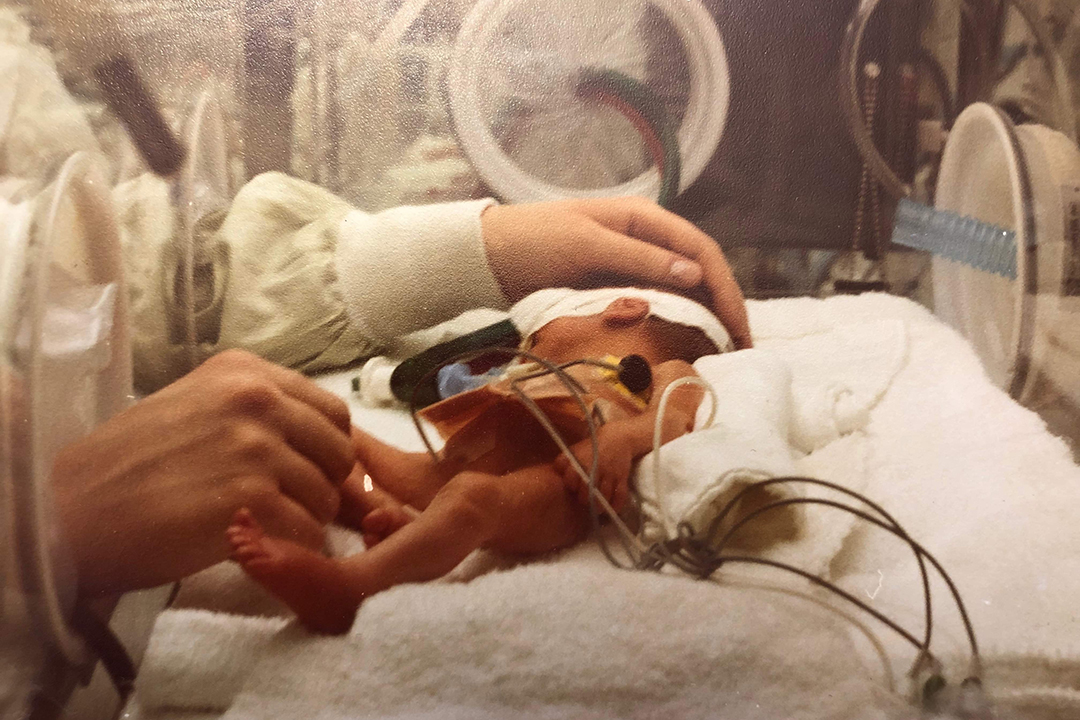

That was the case for Saskatchewan mother M.J. Blaquiere, who went into early labour at 26 weeks in March 1980. Once she realized what was happening, Blaquiere went to the health facility in her community of Edam, a small town in northwest Saskatchewan.

But, like most small communities, Edam’s health facility wasn’t set up to handle a pre-term birth and couldn’t provide the care needed for a premature baby. The local health team told Blaquiere to travel to Saskatoon, but she didn’t make it that far. Her daughter Beth was delivered in North Battleford, which is located about 60 kilometres southeast of Edam.

Although Beth was taken by ambulance to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at Saskatoon’s Royal University Hospital, Blaquiere had to remain in North Battleford until she was discharged.

Babies born pre-term can have significant difficulties. For example, Beth kept forgetting to breathe, and the NICU nurses had to continuously stimulate her every time her breathing stopped.

Beth spent the first three months of her life in the hospital. Although her parents were there as much as they could be, her father had to take care of the family’s farm and could not be with his daughter all the time.

Beth’s parents brought her home when she reached a weight of six pounds, but even so, the three-month-old infant continued to have breathing issues.

“They said she was a high risk for SIDS [sudden infant death syndrome] just because she was a girl and she was a preemie,” says Blaquiere. “I had to give her these meds every four hours, so it was a long time before she slept through the night because she was so used to waking up. It was something to keep her a bit stimulated so she wouldn’t fall asleep and stay that way.”

Fortunately, Beth was one of the lucky ones: she’s now an adult with her own family, and Blaquiere’s pre-term birth had a happy outcome.

For MacPhee, stories like Blaquiere’s experience are what he hopes to change in the future. His research goal is to help ensure that pregnant mothers have more warning of a pre-term birth so they have more time to reach the critical health services they need.

“There are people in rural places that have to travel greater than two hours to give birth because there is no birthing centre in their community,” says MacPhee.

“If they knew they had a bit of time based on a test, then it would make things a whole lot easier for them to plan, organize and not be away from their families for perhaps a month because they’re not sure when it’s [the baby] coming.”

The research team’s foundational work was financially supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Calista Lytle of Saskatoon, Sask., received her Bachelor of Science (Honours) degree in physiology and pharmacology at USask this spring and will begin medical studies at the USask College of Medicine in August. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.