Big attitude helps little horse survive

Jennifer Leier knew her latest purchase, a four-year-old miniature horse named Kimchi, had an attitude — his sassy personality and his champagne grullo colour were why she brought him home to her hobby farm near Prince Albert, Sask.

By Christina WeeseBut on Friday, June 17, 2019, she had no idea that Kimchi’s attitude was about to get them in big trouble — and eventually, back out again.

Kimchi had been gelded at the same time as another one of Leier’s miniature horses. After a few days of recovery, Leier turned out the two geldings. But when she went to bring them in, Kimchi refused to be caught. Leier finally turned out her riding horses in the same pasture, hoping their presence would allow her to catch him.

Kimchi, however, had other ideas. To Leier’s disbelief, the miniature horse attacked Winston, her Fjord-cross gelding. After warning the tiny biting, kicking whirlwind to back off, Winston turned around and kicked — his hoof landing on Kimchi’s right hind leg between his stifle and his hock.

“I knew instantly the leg was broken,” says Leier. “Just from the way he was standing. I was just sick — devastated. I didn’t know what to do.”

She called her local veterinary clinic, but realistically, horses don’t recover from a broken tibia.

“If I wanted to euthanize, they were prepared to help with that,” says Leier. “But [for] anything else — I’d have to call Saskatoon.”

Tibial fracture in miniature

Leier contacted the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s Veterinary Medical Centre (VMC) and talked to large animal surgery resident Dr. Michelle Tucker, who told her to do what she could to stabilize Kimchi’s limb for transport. It was paramount that the broken bone didn’t puncture the skin. A puncture would introduce the possibility of a bone infection from which recovery is nearly impossible.

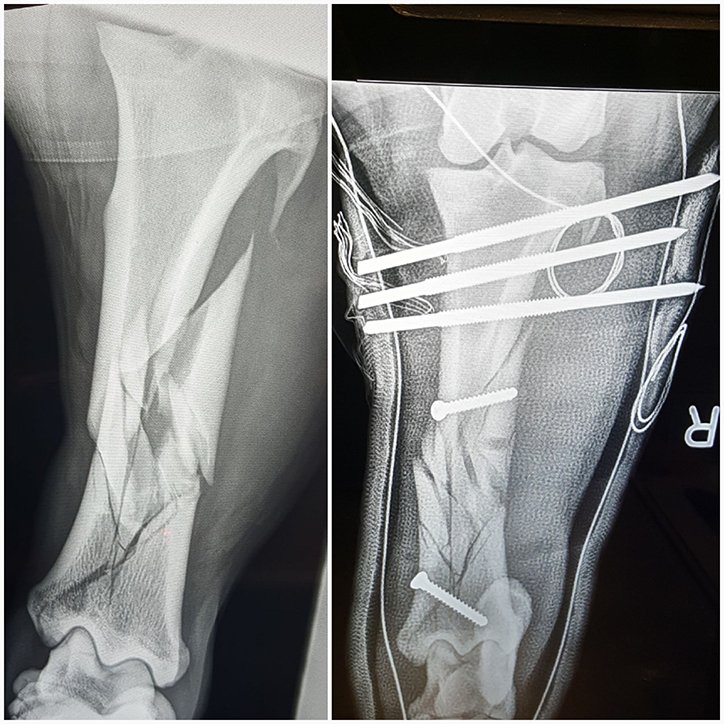

Leier devised a sling for Kimchi in her trailer, using ratchet straps connected to bolts in the roof and a thick Western saddle pad under his belly. With Kimchi stabilized, she made the late-night trip to Saskatoon where the veterinary teaching hospital’s clinical team took radiographs of Kimchi’s leg to assess the damage.

“As soon as I saw it [the X-ray], I started bawling,” says Leier. “We’re talking 12 to 15 pieces of shattered bone in the leg. ‘He’s done,’ I thought.”

Tucker advised euthanasia, but Leier just couldn’t give up. Tucker then suggested calling Dr. James Carmalt, a large animal surgical specialist at the WCVM.

“She [Dr. Tucker] said, ‘If anyone’s going to do something, it’s going to be him,’” says Leier.

After examining the radiographs, Carmalt’s initial reaction was that tibial fractures aren’t fixable in full-size horses. But since Kimchi was a miniature horse, he thought there might be a chance. However, Kimchi still had to make it through the night: Leier slept in her truck with her horse suspended inside the trailer.

“[The sling device] probably saved him,” says Carmalt. “It meant the fracture was not an open fracture, the bone was not poking out of the skin — he kept his weight off it all that time.”

After discussing Kimchi’s potential for recovery, costs and his overall welfare, Leier agreed to go ahead. Lacking enough large bone pieces to use a plate, Carmalt used two screws to hold the largest pieces of bone together, then inserted pins into the tibia’s head to create a transfixation cast. The pins, inserted at a 90-degree angle into the bone, stuck out far enough that they went through the cast, transferring the animal’s weight from bone to cast.

“It makes sort of a ladder,” explains Carmalt. “Because horses’ skin is so thin over these parts of the bone, the distance between the bone and the cast is essentially zero.”

A long road to recovery

Leier knew Kimchi’s recovery was going to be long because she’d been through it herself with a tibia-fibula fracture five years ago. That experience was part of the reason she decided to go ahead with the surgery, along with feeling guilty about Kimchi’s injury.

“I allowed things to happen that I wouldn’t normally have done …. As his guardian, I put him in a position to get hurt.”

Kimchi’s recovery wasn’t smooth. Skin over the original injury’s site sloughed off, creating a large wound that required weekly cast changes. The pin sites also became infected. By the time the pins needed to be removed, clinicians put Kimchi in a cast over a standing bandage. This set up allowed him to be left in his cast for a longer stretch of time — and that’s when he began improving.

By late October, radiographs showed that Kimchi could progress from a cast to heavy-duty support bandages. As the clinical team removed the final cast, Leier recalls Carmalt’s comment.

“He said, ‘Just so you know, there’s a chance it could all fall apart.’ I think that’s the only time [during Kimchi’s recovery] that I felt sick about the whole thing,” she says. “You genuinely feel that you’re out of the woods, and then that!”

‘A tenacious little dirtbag’

The next step was rehabilitation and therapy to help rebuild Kimchi’s atrophied muscles and to improve the range of motion in his hock joint, which had been immobilized in the casts and bandages for months. When Tucker mentioned that there was an aquatic treadmill in the VMC’s small animal rehabilitation centre, that led to a new adventure for the gelding.

The therapy team, led by clinical associates Drs. Kira Penney and Romany Pinto, moved slowly to introduce Kimchi to their equipment: “The first day we weren’t sure how reactive he would be, so we had him stand facing the treadmill and practised filling and draining it so he got used to the noises,” says Pinto.

Once he was accustomed to the noises, the team practised backing Kimchi into the treadmill, getting his hoofs wet as it filled with water, and walking out. Pinto also used a hoist (typically used to help support large dogs with back or neck issues) to hold a sling on Kimchi’s hind limbs, which helped to support him as the team cleaned and wrapped his hoofs to prepare for the treadmill, and to assist him with backing in to the therapeutic device.

He soon progressed to full sessions on the treadmill with water up to his chest. The team used laser, acupuncture and massage to help relax the sore muscles he’d been using to shift his weight throughout his recovery. They also used cavalettis, passive range of motion and underwater treadmill walking to help increase the flexion in his hock.

“By the second week of rehabilitation, we were measuring the range of motion in his hock, and it was changing day to day,” says Pinto, adding that Kimchi took all of the new experiences in stride. The same oversized personality that got Kimchi in trouble also played a big role in his recovery.

“He’s such a tenacious little dirtbag,” says Leier, laughing. “If it wasn’t for his big personality, I don’t think he would have recovered. He never went off his food, he never broke out in a cold sweat. [He just said], okay, now I’m a guy with a cast.”

Carmalt agrees: “I think it was a huge factor in his case … [it was] to the point where Dr. Tucker could issue a voice command and he knew they were about to lift him up or carry him or move him in a particular manner. He is also not a high-strung horse. He looked after himself, which is very important.”

Success stories such as Kimchi’s case are always a team effort — from an owner with the resources to try for recovery, to a patient with the right disposition and patience, to a veterinary team with the skills and resources of a medical referral centre behind them.

“They were so, so good to me,” says Leier. “They really helped me in understanding the overall process; they were very good about going through all the information with me — the good, the bad, the ugly.”

“One of the first things I tell students is that the only time you really lose is when you don’t try,” adds Carmalt. “In this case, the owner … gave us the option to be as creative as we could possibly be, and utilize a team as big as we needed.”

“I think I always would have regretted not trying,” says Leier, who brought Kimchi home on Feb. 20. “He’s got a little hitch in his step. But we have some therapy exercises to work on. In a year’s time, it’ll be interesting to see where he’s at.”

Click here to read more stories in the Summer 2020 issue of Horse Health Lines, publication for the Townsend Equine Health Research Fund.