Burglar bees help spread of honey bee infection

It may sound like a tall tale, but burglar honey bees raiding nearby hives is contributing to the spread of a disease called American foulbrood (AFB) in Saskatchewan.

By Alexandra Wentzell

“It [the disease] affects the developing brood of a colony and can wipe them out, and we can see entire losses of hives,” says Mike Zabrodski, a master’s student in the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s (WCVM) Department of Veterinary Pathology.

Led by veterinary pathologist Dr. Elemir Simko, Zabrodski is part of a team that’s tracking the spread and intensity of AFB infection throughout the province. The researchers are also investigating how the honey bee population is affected by differences in management practices among beekeepers in Saskatchewan.

Beekeepers’ practices, especially those related to disease surveillance and treatment, greatly affect the spread of diseases such as AFB. Colonies managed in a closer geographic range mean that these honey-producing pollinators are more likely to interact with other beekeepers’ hives and equipment.

With more people becoming beekeepers and managing colonies as a hobby or a commercial venture, the density of beehives has vastly increased in the province. And, as bee-to-bee interactions grow, so does the likelihood of AFB spreading to other hives.

“Livestock like cattle usually stay inside a fence, but bees are foraging everywhere. They don’t stay behind a fence and it’s usually tough to know where they are going. [You] can expect that they are [travelling within] five kilometres or less — but they can go more, they can go less,” says Graham Parsons, an apiculture industry specialist with Saskatchewan’s Ministry of Agriculture.

The researchers are performing their work in collaboration with Saskatchewan’s commercial and hobby beekeepers. Their study also includes the WCVM’s research honey bee colonies based at Goodale Farm, which is part of the University of Saskatchewan's Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence (LFCE).

Bacterial spores lead to infection

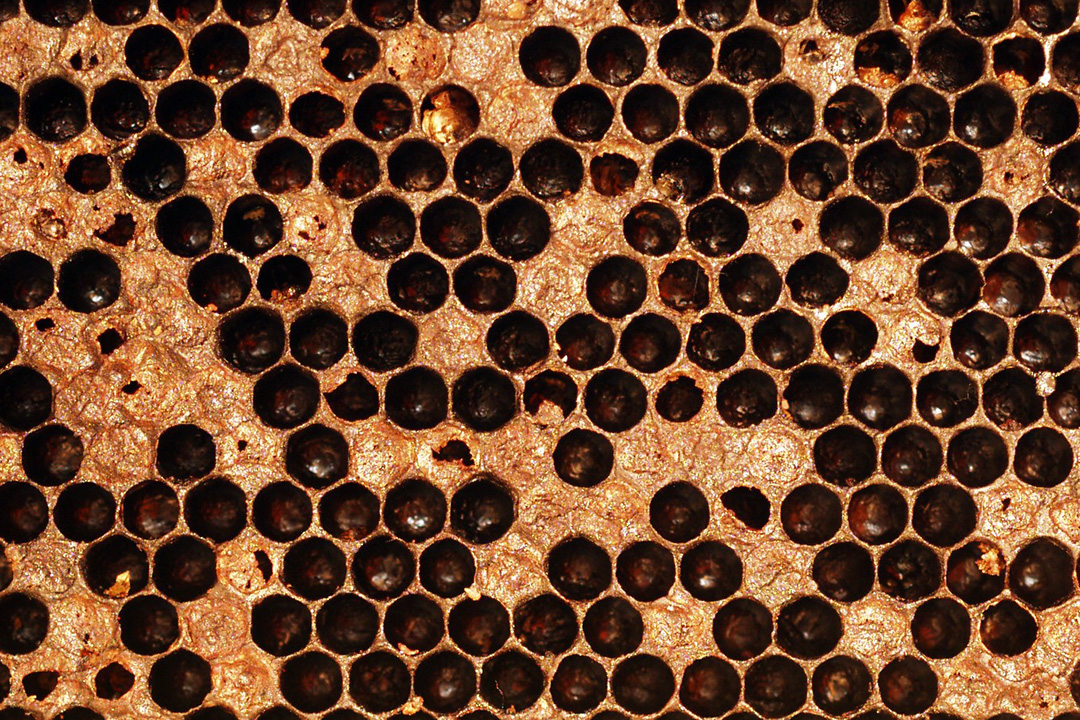

AFB is caused by the spore-forming bacterium Paenibacillus larvae, which is highly pathogenic and capable of surviving in the environment for decades. Once the bacterial disease wipes out a colony’s population, foraging bees can rob the empty, unprotected hives and bring back honey contaminated with AFB spores to their own hives.

“[For] robbing bees … it’s cheap easy resources: they go and steal that honey, steal that nectar, pick up the AFB spores and bring it back to their home colony. And bang — you have another colony infected,” says Parsons.

He adds that all of the equipment in an infected hive is potentially contagious for other beekeepers in the area, which is why he recommends that producers destroy any equipment from infected colonies.

“If the bees are dead, and the equipment is … sitting there for a long time, it can [infect] anyone within bee distance.”

Besides the devastating impact on beekeepers’ livelihoods, losses associated with AFB infection have a ripple effect throughout the province’s agriculture industry outside of honey production. The loss of important pollinators for crop production puts food security at risk, plus AFB spores present in honey prevents producers from selling to premium overseas markets.

Industry experts say a lack of training and education may be playing a particularly significant role in the transmission of this disease. As Parsons points out, new smaller-scale beekeepers or hobby farmers may not understand the signs of AFB infection in their hives, how to deal with it, or the importance of destroying infected equipment.

Surveillance, education vital to disease prevention

The ongoing AFB surveillance project aims to identify management practices as pre-disposing factors for increased risk of infection, as well as those that reduce them. Researchers are evaluating how beekeepers handle their bees as well as the impact of buying used equipment, bringing in bees from outside sources and antibiotic usage.

“All of those different aspects when it comes to management — those are the things we are trying to look at,” says Zabrodski.

By culturing honey samples taken from commercial and hobbyist operations, the researchers are also gathering information about the location of high-risk areas in the province through the identification of spore counts and resulting infection levels.

This process mimics strategies already being performed on a mandatory level in other countries.

“[In] New Zealand and Germany, those countries don’t use any antibiotics when it comes to prevention, they actually have surveillance programs in place where producers will send in honey samples to have those honey samples tested for spores and the readout that the producers will get will tell them if they are at a low, medium or high risk for outbreak for disease and how to act accordingly,” says Zabrodski.

“Here in North America, however, we rely a lot on antibiotic use. And when it comes to antibiotics, [producers are] usually treating twice per year to try and keep this disease in check and from becoming a problem.”

By comparing risk factors and infection levels, this project also aims to identify the efficacy of preventive, or prophylactic, antibiotic usage as a management practice, which is the current method of prevention in North America.

Zabrodski says the best way to prevent further spread of the disease is to better inform producers for effective management of AFB. By training and informing new beekeepers, the province’s honey bees will hopefully be managed in a more uniform way that reduces the risk of AFB transmission and infection.

The WCVM research team’s AFB surveillance work is financially supported by Saskatchewan’s Agriculture Development Fund, Mitacs and the Saskatchewan Beekeepers Development Commission.

Alexandra Wentzell of Calgary, Alta., is a Bachelor of Science (animal bioscience) graduate of the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Agriculture and Bioresources. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.