Polar disease research merits award

Insects are a great resource in learning how climate change affects diseases that are transmitted in the Arctic, which is warming at two to three times faster than other parts of the world.

By Katie Brickman-Young

“Insects are sensitive to changes in temperature and precipitation, so my project is looking at developing a baseline for vector-borne diseases in the Arctic,” says Kayla Buhler, a PhD student in the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Veterinary Microbiology at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

Supervised by Dr. Emily Jenkins, the focus of Buhler’s research is how vector-borne diseases are transmitted from insects to wildlife in the North.

“My project aims to understand the disease ecology of these viruses and bacteria up north, especially how these different pathogens are being transmitted to wildlife,” says Buhler.

In May, Buhler received the Éric Dewailly Memorial Award in Health Sciences, named in honour of Dewailly, whose own environmental health research was focused on the Canadian Arctic and its people. After Dewailly’s accidental death in 2014, this award was established in honour of his work by the Northern Scientific Training Program, administered by Polar Knowledge Canada.

“This award, now $2,500, recognizes student excellence, for which Buhler was an obvious choice,” says Jenkins, Buhler’s supervisor and chair of the USask Northern Studies Committee, which nominated her for the award. Almost 40 universities across Canada can nominate students for this prestigious award.

“The support from Polar Knowledge Canada has gone towards me having the opportunity to connect with communities and keep those relationships strong,” says Buhler.

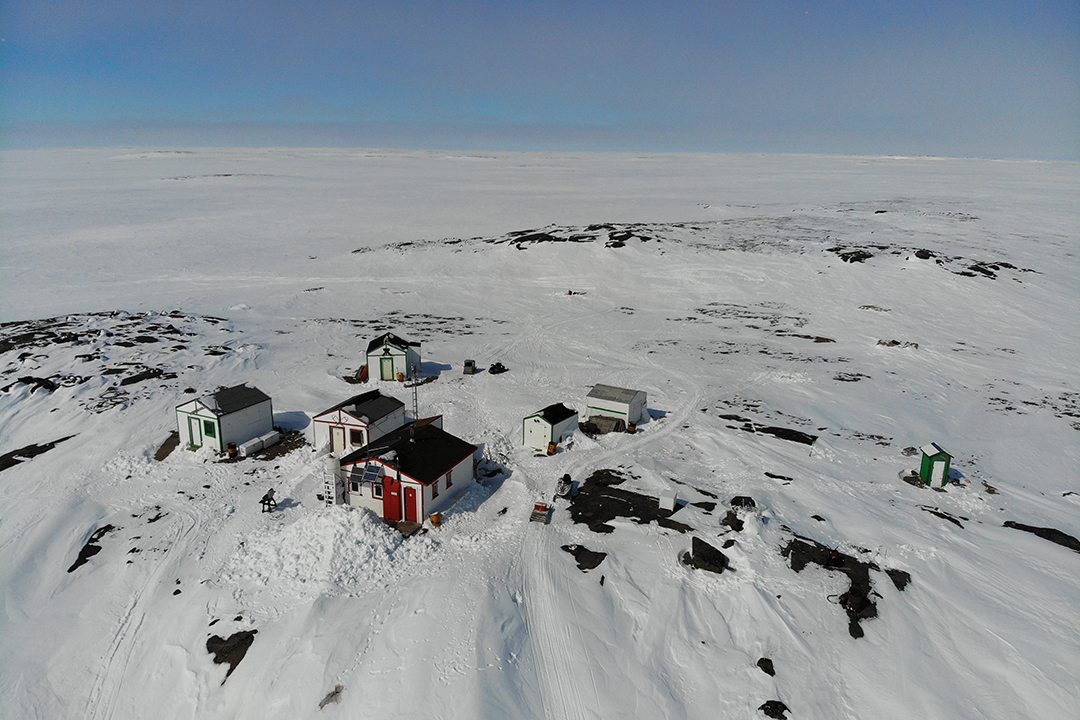

Buhler spends three months every summer at her main field site in Karrak Lake, Nunavut, compiling research by collecting samples from Arctic foxes — her main research animal.

“The summer is the best time to be looking for active infection with vector-borne diseases,” she says. “We do some collection of insects, but I do a lot of work with rodents and foxes.”

The days are long for Buhler and her team. They begin work at 11 a.m. by getting things ready around camp and doing necropsies on geese. By early afternoon, they take a boat to the mainland, hike an hour or two to their location and set up fox traps.

“We sit in the tent and watch for fox pups to come out of their dens,” she explains. “Once the fox pups are in the trap, we go and collect a blood sample and then try and get them back to their dens as quickly as possible.”

The team spend the afternoon and evening gathering collections from the foxes before returning to camp around 2 a.m.

Buhler is looking for antibodies in the blood of the foxes, particularly for tularemia — a zoonotic disease caused by the bacterium Francisella tularenis. Rodents, a primary source of food for Arctic foxes, are important reservoir hosts for this pathogen.

“Generally, when we are looking for an active infection, we usually would use PCR (polymerase chain reaction assays), which is looking for DNA versus the antibody. But with foxes, we look for any evidence of a previous infection.”

The team is also looking for antibodies for viruses that are transmitted by mosquitoes as well as for Bartonella bacteria.

“There are different species of Bartonella that we’ve found,” Buhler says. “The one that has been published so far is Bartonella henselae, which is the agent of cat-scratch disease.”

That finding is surprising to Buhler because there are no cats or cat fleas up in the Arctic, so they aren’t entirely sure how the disease is being transmitted.

“The foxes have a close relationship with the goose colony up there, and a lot of the nests in the colony are infested with a nest flea,” she explains. “We’ve found Bartonella henselae in the nest fleas and figured out that they are likely involved in transmitting Bartonella to Arctic foxes.”

Buhler and other members of the Canadian Arctic One Health Network gather these samples to generate a baseline of the prevalence of diseases across the Arctic. This baseline gives communities and public health the information they need to keep everyone safe.

“One of the biggest things for my project is to try and unwind the complicated transmission cycles in the Arctic. Once we know how something is transmitted or what reservoir hosts are involved — how vectors become infected and how they transmit to other wildlife — we can start to find ways to implement control methods,” explains Buhler.

Despite the complications that the COVID-19 pandemic has created for Buhler’s research and her ability to travel, she’s taking this time out of the field to dive more into the literature and the lab to answer questions about these emerging pathogens in the Arctic.

“We know that in our Arctic fox population, tularemia is circulating as well as Bartonella. So, there are some particular questions about whether these pathogens are emerging or if they are already established and whether or not vectors can maintain these pathogens over the winter,” Buhler says.

“For example, do fleas require migratory hosts to introduce these pathogens every summer or can they maintain them over the winter when its -50 C, emerging from the nests in the summer already infected?”

Buhler hopes to return to Nunavut whenever it is safe to continue her research and visit with the communities. Due to the global pandemic, it will take an additional year to complete her PhD degree sometime in 2022 or early 2023.

“It is a bit of a delay, but I love what I’m doing, so I’m not that bummed by it,” says Buhler.