Can corn help to extend winter grazing?

Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan are exploring new ways to extend the winter grazing season for cattle by using what’s left after farmers harvest corn.

By Lana HaightGrazing pregnant cows in fields during the winter is not new in Western Canada, but no research has been conducted on how well animals fare when they graze on corn residue — the leaves, the stalks, the husks, the cobs, everything that’s left in the field after the high-moisture corn kernels have been harvested.

“We were very limited in where we could grow corn in Canada, but it’s become more popular because new hybrid varieties of corn have popped up that are made for shorter season and lower temperatures,” says Rachel Carey, a PhD provisional candidate who is co-supervised by USask animal scientist Dr. Greg Penner (PhD) and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada researcher Dr. Tim McAllister (PhD).

“Profit margins for farmers and cattle feeders are extremely tight. Anything they can do to decrease the cost of feeding animals while maintaining (growth) performance is important. We are looking at the possible economic benefits of using these alternative corn products."

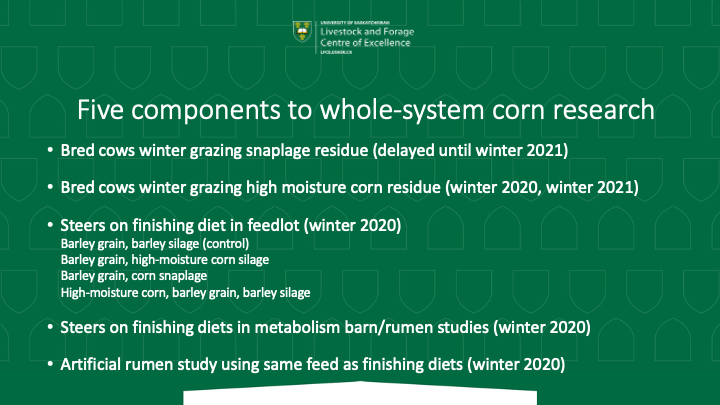

Carey’s research is addressing the old adage “waste not, want not” with her whole-systems study.

In the spring of 2020, 200 acres of corn was seeded at the university’s Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence (LFCE), which is located south of Clavet, Sask.

Seventy-one acres were harvested as "snaplage," the term used to describe a method where the ear of the corn is harvested or what would be snapped off the corn stalk, while the 94 acres were harvested as high-moisture corn and 35 for corn silage. In all three cases, the feed was fermented and, starting in February, the corn is being fed to two groups of cattle at the centre’s feedlot and in its metabolism barn. Carey will track the animals’ weight gain and evaluate how well the animals are digesting the corn feed.

She started the bred cow component of her research on Nov. 25 when 30 cows began feeding on the high-moisture corn residue left in windrows. Another 30 were in a control group, feeding on barley that was swathed at the hard dough stage.

It’s been an eye-opening experience for Carey, who was raised in Texas.

“This is my first winter grazing study ever! I thought Canadians were crazy when I first heard about winter grazing, but these girls are pros. Once you have the cows trained to look for the swaths and nose around in the snow, they find the feed. I was amazed at how fast they found the swaths. They knew exactly where they were.”

To ensure that the cows ate all the feed in each paddock, electric fence was moved about every three days. The cows were allowed access to a new paddock in the pasture after they had cleaned up the residue or swaths in one paddock.

“If you allow access to the whole field, they’ll go and get all the good parts. You have to force them a little bit to eat what they don’t like, kind of like getting your kids to eat peas.”

Carey wasn’t able to feed cows using the snaplage residue because a winter storm in early November covered the snaplage residue with snow too deep for the cattle to find the feed.

Carey’s project took another hit with freezing rain and heavy, wet snow in early January. She and Penner made the difficult decision to move all the bred cows off the fields and to the centre’s Forage and Cow-Calf Research and Teaching Unit where they will continue to be fed.

As disappointed as she is, Carey realizes that she is conducting real world research with real world conditions, the same unpredictable weather conditions cattle farmers in Western Canada face every year.

“It’s hard to compete with Mother Nature,” says Carey.

While the winter grazing was a few weeks short of Carey’s plan, all is not lost. She is still collecting and analyzing information. The cows on the high-moisture corn residue as well as those on the barley swaths maintained their body weight and their body condition score, indicating how much fat the cows are storing as they head into calving. And the animals have left behind valuable fertilizer.

“There’s a lot of manure out there. It’s been packed down, trampled down, broken down by the animals moving over the land. We’ve increased the nitrogen content of the soil. The field will need less fertilizer next year.”

The road that led Carey to Saskatoon is long and has taken a few turns. She grew up in a small city in Texas and, while she didn’t grow up on farm, she occasionally visited her uncle’s cattle operation.

After teaching high school for five years, Carey went back to school to pursue veterinary college but after taking a course in ruminant nutrition at New Mexico State University, she switched gears and enrolled in a master’s program in animal science instead. From there, she worked for three years with a feedlot consulting company based in Calgary, Alta.

The research funded by Saskatchewan Cattleman’s Association and Beef Cattle Research Council and the seed is provided by Pioneer Hi-Bred.

Carey’s research will continue until the summer of 2022.