Saskatoon COVID-19 wastewater testing results now online

Saskatoon residents now have access to the results of wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) testing for SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing COVID-19 — thanks to a partnership between University of Saskatchewan (USask) researchers, the City of Saskatoon and the Saskatchewan Health Authority.

The latest data is available on the university's Global Institute for Water Security website. Data will be updated on the site every Monday by noon.

Here is some of the information available on the site:

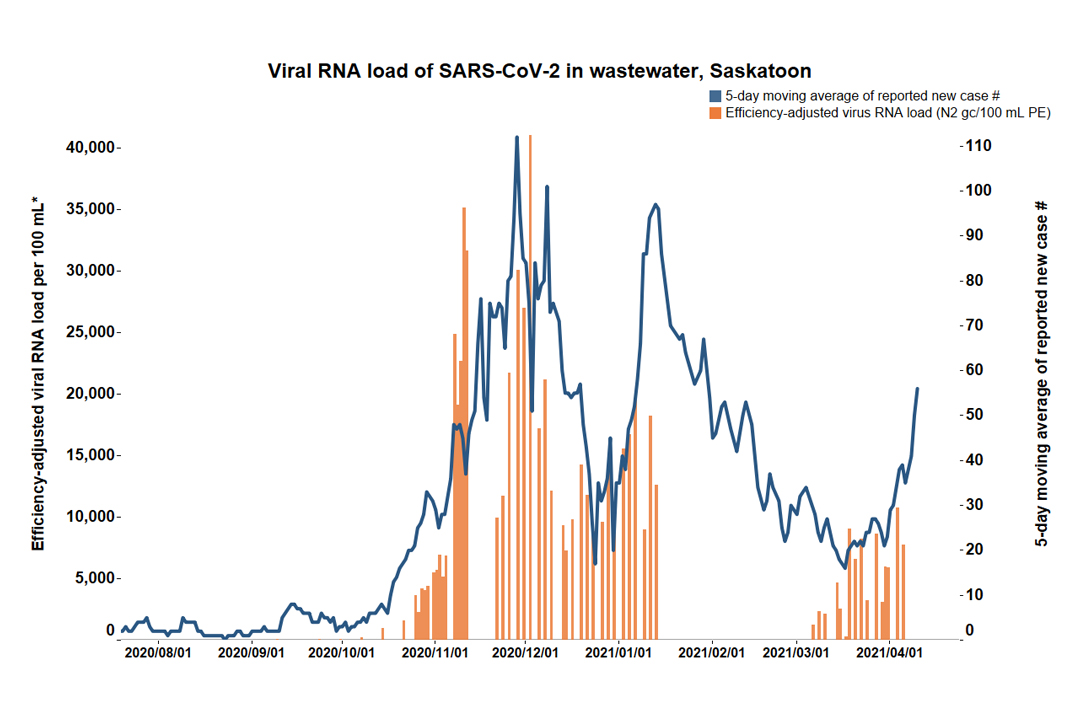

- From April 1 to April 5, an 86 per cent increase in SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA load in Saskatoon's wastewater was observed compared to the previous week (up to March 31).

- These recent increases in viral RNA load predicted a continued increase in the number of new cases in Saskatoon over seven to 10 days (after the sample collection date of April 5).

- Currently, an average of 50 per cent of the viral RNA load in wastewater is contributed by the B117 variant of concern, a 285 per cent increase from the previous week's data (up to March 31). This suggests that this variant of concern, first detected in the U.K., is spreading and will likely soon become the predominant one in Saskatoon.

- No testing of other variants was done, but methods for detecting other variants are under development. Samples have been sent to the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Man., for genomic sequencing.

- All data has been shared with Saskatchewan health authorities.

Viral wastewater surveillance is a leading indicator of impending surges in case numbers that precede increases in new positive cases by seven to 10 days. By gathering this information, the team and its partners are able to warn of upcoming increases in positive cases. Most people start shedding SARS-CoV-2 through their feces within 24 hours of being infected. This viral signal detected in wastewater helps provide population-level estimates of the rate of infection in a city.

This information has the potential to complement COVID-19 swab tests, which are limited because symptoms may not appear for up to five days after infection.

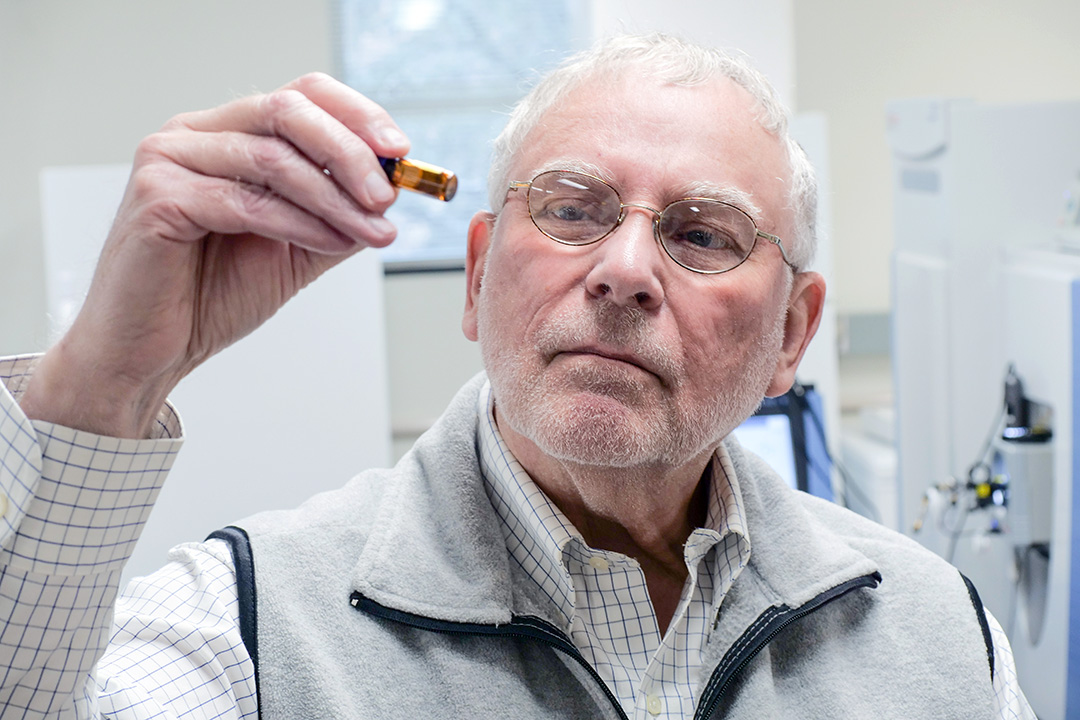

The project is led by USask researchers John Giesy (Toxicology Centre and Western College of Veterinary Medicine), Kerry McPhedran (College of Engineering) and Markus Brinkmann (School of Environment and Sustainability, Global Institute for Water Security and Toxicology Centre).

The team also includes toxicologist Paul Jones, program manager Yuwei Xie, engineering PhD student Mohsen Asadi, and Toxicology Centre research associates Femi Oloye and Jenna Cantin.

When interpreting these data, increases in the viral signal in the wastewater are roughly indicative of increases in new positive cases that can be expected in the following seven to 10 days after sample collection, and decreases are roughly indicative of likely decreases in new positive cases.

It is important to note that the magnitude of these changes is not always proportional (for example, a four-fold increase in the viral signal does not always equal a four-fold increase in case numbers). It should rather be seen as a gauge for the direction of change.

This research was initially funded through the USask-led Global Water Futures (GWF) program and was recently awarded funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada.