Honey bee disease gains ground in B.C. and Saskatchewan

One of the latest projects in the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) honey bee health research lab is a tale of two provinces.

By Dana LiebeA bee collects pollen from a blueberry flower. Although the disease has been a long-term problem for beekeepers in B.C., European foulbrood disease is now becoming more common in Saskatchewan. Photo: iStockphoto.com.

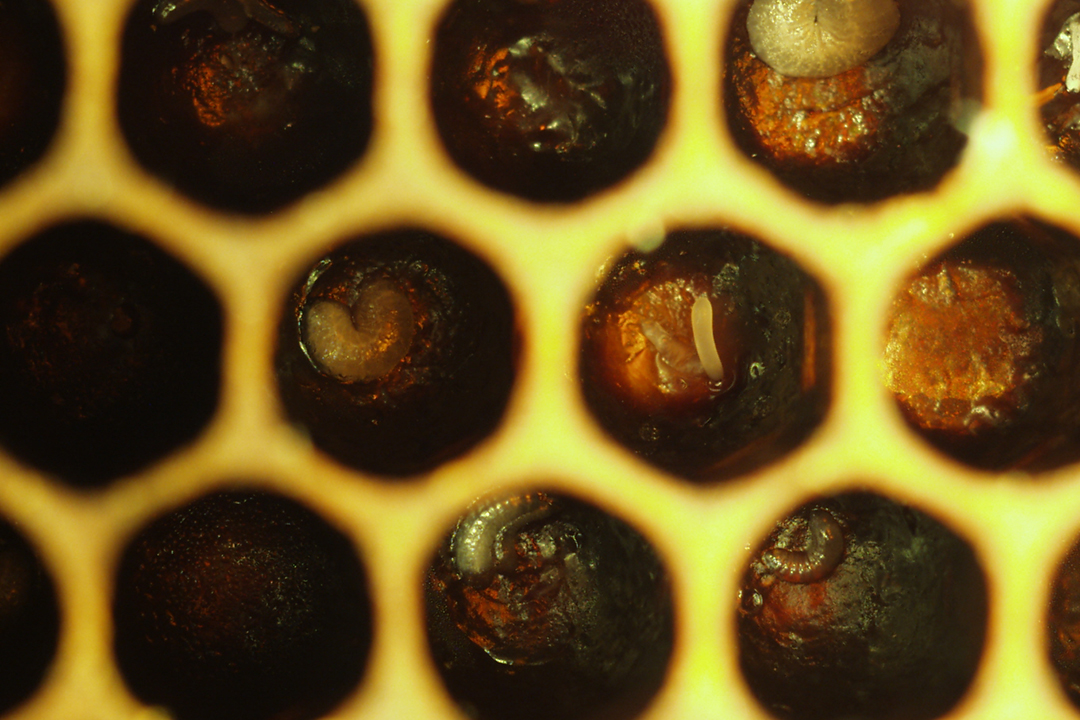

Scientists are investigating the differences between outbreaks of European foulbrood disease (EFB) in British Columbia and Saskatchewan honey bees. EFB, which is caused by the bacterium Melissococcus plutonius, affects young honey bee larvae. Although the disease has been a long-term problem for beekeepers in B.C., it’s now becoming more common in Saskatchewan.

Geoff Wilson, the provincial apiculturist for Saskatchewan, recalls seeing EFB in a total of two hives between 2009 and 2017. In recent years, however, he has seen cases in up to seven Saskatchewan hives per year. Not only are the number of cases increasing, the disease also appears to becoming more severe.

“Symptoms tend to arise when there is a secondary stress,” explains Dr. Jenna Thebeau, a WCVM graduate student who is part of a research team led by Drs. Elemir Simko and Sarah Wood. She adds that these secondary stresses may differ between the provinces as beekeepers in each province have different management practices.

Some stressors may include environmental factors such as the length of winter, availability and quality of forage, and the amount of precipitation. Other factors include past infection and the practices of other beekeepers in the surrounding areas. Although many of these elements can affect colonies in both provinces, their impact may be felt quite differently.

For example, while each region is subject to nutritional stress secondary to the environment, the causes may vary between provinces. In B.C., nutritional stress might occur because the blueberries are not in bloom or are not providing acceptable nutrition to the bees.

In Saskatchewan, however, nutritional stress is common during the period of dearth that honey bees experience in early spring when they have used most of their stored resources and other crops and pollen sources aren’t in bloom.

In Saskatchewan and B.C., honey bee colonies are exposed to different forages as well as different pesticides used to protect these crops against various pests, which could have an impact on honey bee resistance to diseases.

The two provinces also have major differences in apiary management styles, and that factor could be another element affecting their susceptibility to disease.

A substantial number of B.C. beekeepers use migratory beekeeping, a type of management that involves moving their hives to different crop fields to provide pollination services. On the other hand, almost all Saskatchewan beekeepers strictly focus on honey production. Their hives remain in the same location for the season with the bees sourcing pollen from surrounding crops.

These different management styles may result in dissimilar stressors. For example, in B.C. the movement between different crops could be a stressor, but in Saskatchewan, management practices could become a stressor if the hive is surrounded by poor quality or late-blooming monoculture crops.

The density of beekeepers in an area may also affect a hive’s susceptibility to disease: “If [bee] yards are close enough in proximity, the bacteria can be transmitted (usually by robbing) from one apiary to another,” says Thebeau.

The increasing number of hobbyist beekeepers in Canada could make hive density an important factor. For that reason, more experienced beekeepers may need to focus on educating new beekeepers so they’re able to identify signs of the disease and correctly use integrated pest management strategies and treatments for disease control and prevention.

Thebeau also notes that the disease can be transmitted by moving equipment between apiaries. That’s important information for beekeepers in both Saskatchewan and B.C. since they could spread the disease by sharing equipment with nearby beekeepers or through the migratory management practices of B.C. beekeepers.

Genetics may be another factor that affects disease susceptibility. All honey bees in Canada originate from European honey bees (Apis mellifera ssp. mellifera, carnica or linguistica). Bees of different genetic lines may have different hygienic behaviour. For example, they may have differing speeds at which they detect and remove infected larvae and prevent spread of diseases within a colony.

The severity of the disease can also be affected by a variable virulence of the strain of M. plutonius that’s causing the disease. Since there can be many strains of the bacteria, the researchers will compare the different bacteria causing outbreaks in each province. By experimental infection of honey bee larvae with these different bacteria strains, they can compare the virulence and pathogenicity of Saskatchewan bacteria compared to those from B.C.

By investigating the effects of host, pathogen and environmental factors on the increased incidence of European foulbrood disease in Saskatchewan and B.C. honey bee colonies, the WCVM research team hopes their findings will help beekeepers in both provinces develop strategies for protecting their young honey bees from EFB.

This research project has received financial support from Project Apis m., British Columbia Blueberry Council, Mitacs and the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund.

Dana Liebe of Regina, Sask., is a third-year veterinary student at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) whose research position was supported by the USask Student Research Assistant (USRA) program in 2020. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.