Collaboration key to research funding success

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) has awarded $810,000 over five years to a diverse team of University of Saskatchewan (USask) researchers who are embarking on an ambitious, three-part project to advance the understanding of cystic fibrosis (CF).

By Jeanette NeufeldThe CIHR funding will aid the team in exploring the cellular processes that occur in the lungs of patients diagnosed with CF, paving the way for potential new ways to treat this chronic and often fatal disease.

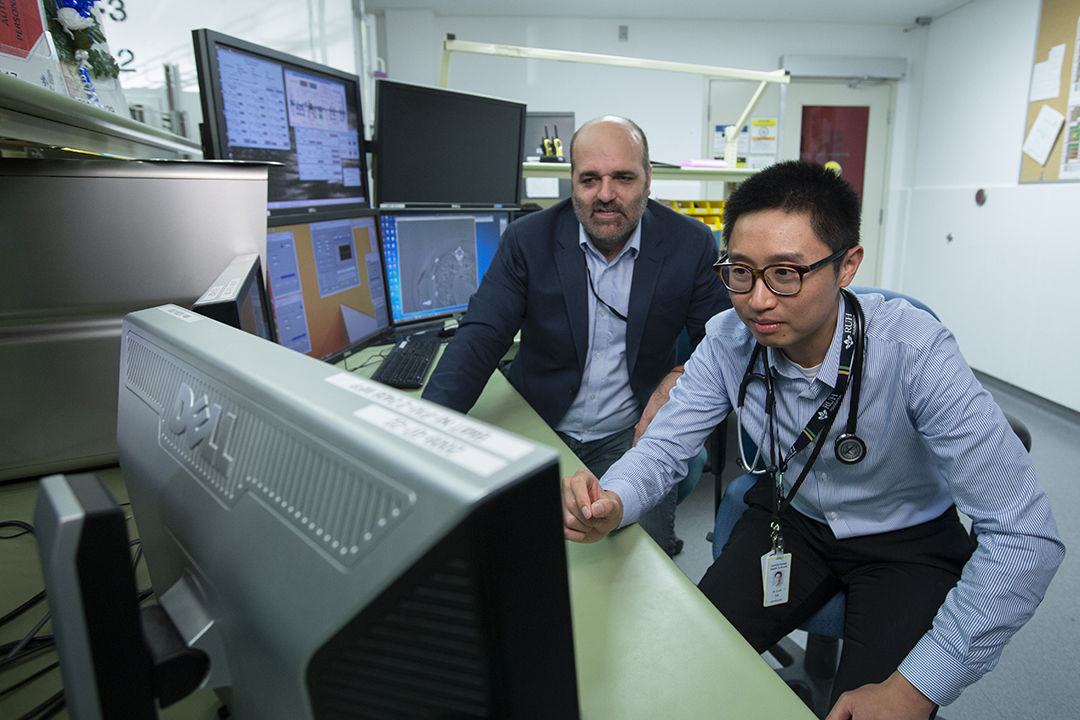

“There is much that the scientific community is still learning about cystic fibrosis lung disease,” says Dr. Julian Tam (MD), a respirologist in the USask College of Medicine and director of the Saskatoon Adult Cystic Fibrosis Clinic.

USask researchers have made big strides in understanding CF through an ongoing collaboration led by Tam and his colleague Dr. Juan Ianowski (PhD), a USask College of Medicine physiologist. The CIHR funding will allow them to harness the expertise of their team’s diverse group of USask specialists, which includes two physiologists, a molecular biophysicist, two medical doctors and a veterinarian.

“The One Health aspect is really important. This is really the only team in Canada that can do this work because of what we have,” says Dr. Julia Montgomery (DVM), a large animal internal medicine specialist at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), who will expand the cellular research using live animal models.

The research team has access to technologies and personnel at the Canadian Light Source’s synchrotron at USask. Researchers at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO) on campus and USask’s Prairie Swine Centre are also providing expertise in raising pigs for CF disease modelling.

“If we removed a single person … we would not get this grant. It’s a true collaboration,” Ianowski says.

Moving forward on cellular understanding

CF research is moving swiftly. The specific cell type that the USask researchers plan to study — pulmonary ionocytes — was first described in Nature less than five years ago. The pulmonary ionocyte is a rare cell type that has been described to express a high amount of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. When this protein is expressed incorrectly because of a gene mutation, CF lung disease occurs. Someone who inherits a faulty CFTR gene from each parent will be born with the disease.

CFTR can have thousands of distinct mutations. Scientists know the protein helps regulate movement of ions in and out of the cell and helps to maintain the balance of salt and water on many surfaces of the body, such as the lung. An imbalance of salt and water on these surfaces results in some of CF’s clinical signs such as inflammation and infection in the lungs and airways.

Secretory cells, the second type of cell under investigation, express a smaller amount of CFTR but appear more frequently.

“These two cell types that we didn’t know were there before have a bunch of surprises,” says Ianowski.

The USask team’s goal is to understand the role of these two cell types — critical information needed to help progress potential treatments.

Recent advances have led to the development of a CFTR modulator called elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor (Trikafta), a drug that acts on the faulty CFTR protein. The medication is effective for about 90 per cent of CF patients. The remaining 10 per cent have rarer mutations, which don’t respond to this treatment.

“As a physician, I wish I had highly effective therapies available for all of my patients,” says Tam. “It can be challenging for patients and their loved ones given that there is not a highly effective CFTR modulator available to them.”

A potential treatment for this subset of the CF patient population is targeted gene therapy, but more information is needed before researchers can develop this type of treatment.

“To be able to do gene therapy, one needs to have a clear target: where should the gene be inserted? Understanding the cellular basis of the disease has become not just a point of curiosity, it’s a real problem for the development of the field. If we don’t know what cells we’re supposed to fix, the technique cannot be developed,” says Ianowski.

Diverse expertise nets funding success

The USask research team’s initial work was supported by research grants from the Respiratory Research Centre, the USask College of Medicine and Cystic Fibrosis Canada. These grants allowed them to complete preliminary research needed to secure the larger CIHR grant.

Ianowski first worked with Dr. Veronica Campanucci (PhD), an electrophysiologist in the USask College of Medicine, to develop methods to identify ionocyte and secretory cells in cell culture and airway tissue to study their function at a single cell level using high resolution techniques.

The project’s next phase is to learn more about how these novel cells influence the disease process first at the single cell level, then in a CF pig model, and finally in human patients.

Montgomery and Dr. Chung-Chun (Anderson) Tyan (MD), a respirologist in the USask College of Medicine who specializes in human lung procedures, will use a specialized probe advanced through a bronchoscope (a camera attached to a thin lighted tube) to study the pigs’ airways and examine the animals’ damaged lung tissue to understand the cell behaviour. The CF research dovetails with another interdisciplinary project, in which Tyan and Montgomery are working to develop new techniques for diagnosing interstitial lung disease.

In the study’s next phase, Tyan will conduct bronchoscopy procedures in human patients, who will be recruited for the study by Tam through his clinical practice.

After the researchers have gathered their information, they’ll turn to Dr. Asmahan AbuArish (PhD), a new faculty member in the USask College of Medicine’s Department of Anatomy Physiology and Pharmacology, to help with the third objective of their project: resolving the CF abnormalities within cell culture.

The team was brought together through connections made at the USask Respiratory Research Centre, and each researcher brings a unique skillset to the project, along with enthusiasm and unique expertise honed by years of study in their respective areas.

The broad group of people working on this project is essential to successfully receiving funding, says Ianowski.

“The science that we do is collaborative. This was a team effort. Everyone tried to produce as much data as they could, which was very important,” he says.

“One of the advantages we have is that we can connect the College of Medicine, the CF Clinic and the CF pigs — all of that creates a proposal that is really unique.”

Ultimately their goal is to improve the lives of patients who experience this difficult disease.

“I think there is a bright future. Gene therapy is hard, and it’s going to be a lot of work ahead, but there is a real shot. No one knows the future, but there are reasons to be optimistic,” says Ianowski.

“It’s a real privilege to be part of a field that’s making such massive changes in the patients’ lives.”