Llamas and alpacas: potential animal models for reproductive research?

A study at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) promises not only to provide important information about llama and alpaca reproduction but also to determine if the camelid species could become animal models for reproductive research.

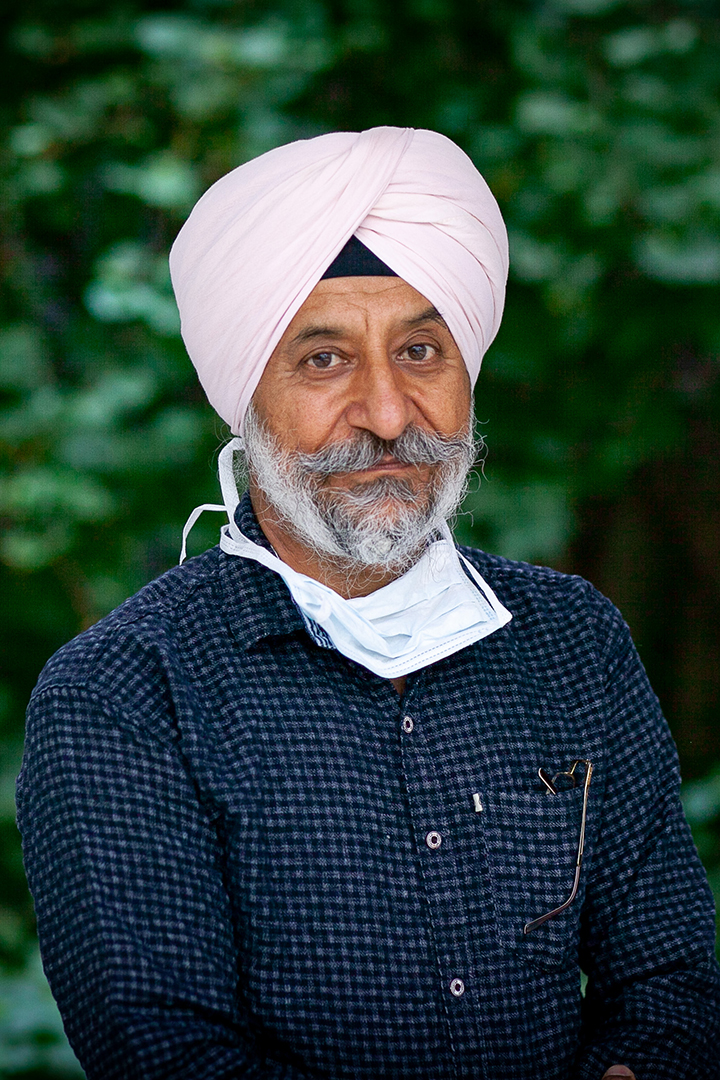

By Muhammad Abdullah Shakeel

In recent years llamas and alpacas have become more popular in North America. As a result, veterinarians are seeing more and more camelid patients in their clinics.

Although the two species are similar enough to cross breed, little is known about their reproductive systems — and that’s a concern for Dr. Jaswant Singh (BVSC&AH, PhD), a reproduction specialist at the WCVM.

“From a veterinary perspective there is insufficient reproductive information that compares both llamas and alpacas,” says Singh, a professor in the college’s Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences. “There is no direct comparison that we can make.”

This lack of information prompted Singh to initiate a research project aimed at examining the reproductive anatomy of the two camelid species. Using transrectal ultrasonography, he and his research team have been studying the ovarian follicular and luteal dynamics in alpacas and llamas.

Transrectal ultrasonography, a technique that produces images of internal body structures, is a useful tool for examining the ovaries and then analyzing them to determine the number of follicles (fluid-filled structure containing developing egg), their sizes and their relative position in the ovary. Scanning ovaries sequentially over days and weeks provides useful information on change in growth pattern of follicles.

Since camelids are generally induced ovulators, they don’t ovulate unless they have mated with a male. As a result, the researchers can examine the ovaries without ovulation having taken place. They can also study follicular dynamics in the absence of the corpus luteum — a structure that typically forms when a dominant follicle ovulates.

As part of their investigation, Singh and his team are also studying and comparing the luteal phase in camelids. After inducing ovulation with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), the researchers use an ultrasound imaging technique called colour flow Doppler to detect the corpus luteum, visualize the extent of vascularization (formation of blood vessels) around it, and observe its function.

“It [camelid reproduction] is not very similar to human beings, but there are a couple of very critical similarities between the reproductive cycles of the two,” says Singh.

The pre-ovulatory dominant follicle develops in both humans and camelids under a very low progesterone environment when there’s no corpus luteum, explains Singh. In contrast, other animal models such as cattle develop their dominant follicle under high progesterone levels due to their long-lived corpus luteum.

In addition, camelids can develop hemorrhagic anovulatory follicles (HAFs), a condition that’s common in humans and doesn’t exist in many domestic animals.

Since these similarities exist, camelids as animal models could be used to mimic and learn more about the development and treatment of HAFs as well as other human reproductive conditions.

From a veterinary perspective, this research will add important information to the field of theriogenology — an area focusing on the physiology and pathology of animal reproduction. This increased knowledge leads the way to additional research aimed at developing treatments, improving animal health, testing pharmaceutical drugs and developing new breeding strategies.

Learning more about the differences between llamas and alpacas will provide fundamental knowledge about the follicular and luteal dynamics as well as reproductive endocrinology.

“This knowledge forms the basis of future applied science,” says Singh. “The data that we collect and its understanding will play an important role in the development of reproductive strategies in these animals. This will not only allow us to answer very specific questions about these animals but also help us refine any future experimental protocol.”

Muhammad Abdullah Shakeel is a fourth-year student in the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Arts and Science who worked as a summer research student in 2021. His story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.