USask researchers devise strategies for faster disease detection in honey bees

While the rise in antimicrobial resistant pathogens is an issue affecting all species, a team of University of Saskatchewan (USask) researchers are focusing their efforts on honey bees — investigating how they can reduce the use of antibiotic drugs for managing disease in the pollinator species.

By Lara Reitsma

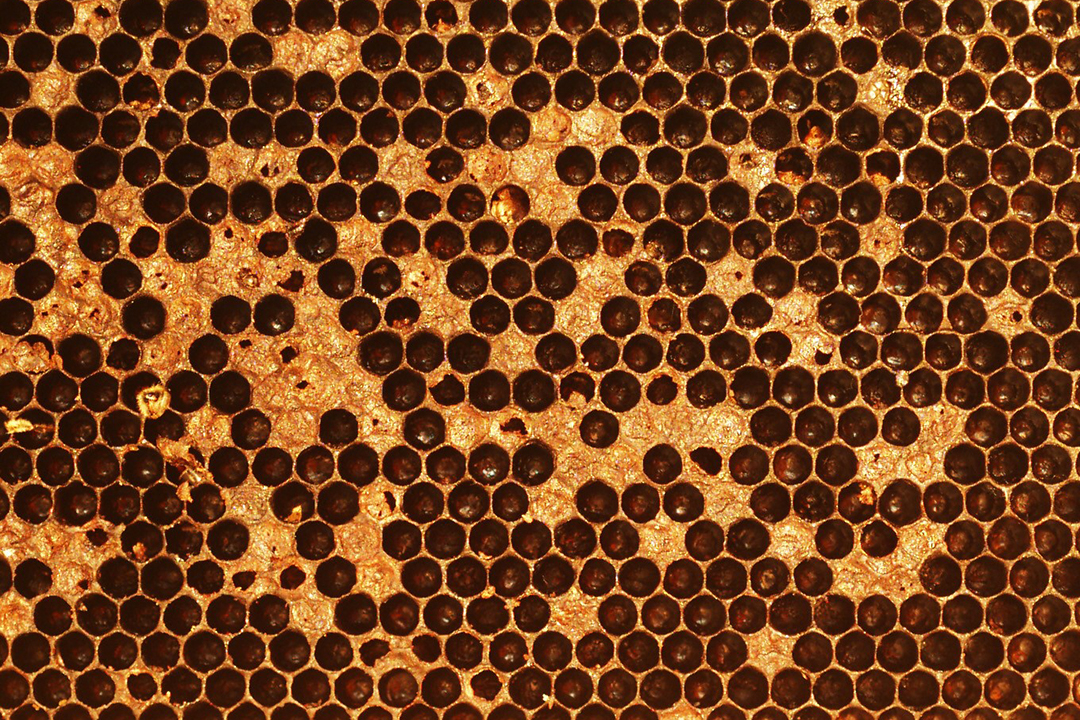

The honey bee health research group at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) is investigating several diseases that affect honey bees, including a highly infectious disease called American foulbrood (AFB) that’s caused by a bacterium called Paenibacillus larvae.

AFB is incredibly deadly to young honey bee larvae, and it often causes widespread colony death that results in significant economic losses for beekeepers.

“Paenibacillus larvae produces spores that spread the infection,” says Dr. Michael Zabrodski, a veterinary pathologist at Prairie Diagnostic Services. He’s also a former member of the WCVM’s honey bee health research team that’s led by veterinary pathologist Dr. Elemir Simko in the college’s Department of Veterinary Pathology and Dr. Sarah Wood, the University of Saskatchewan’s new Pollinator Health Research Chair.

“These spores are very resilient, can persist for decades, and are capable of surviving common disinfection practices, which makes disease management difficult for beekeepers.”

Zabrodski, who completed his Master of Science degree program in May 2022, conducted AFB-focused research for his master’s thesis.

Prevention and treatment of AFB — as well as other bee diseases — is further complicated by the fact that bees don’t just stay close to their hives. In fact, they often fly relatively far away from their home yards, and they may interact with bees from other hives along the way.

Although AFB is currently managed with antibiotics, the drugs aren’t capable of destroying the spores and eliminating the disease. In addition to other costs associated with antibiotic use, scientists are very concerned that routine use of these drugs is contributing to the worldwide increase in antimicrobial resistance.

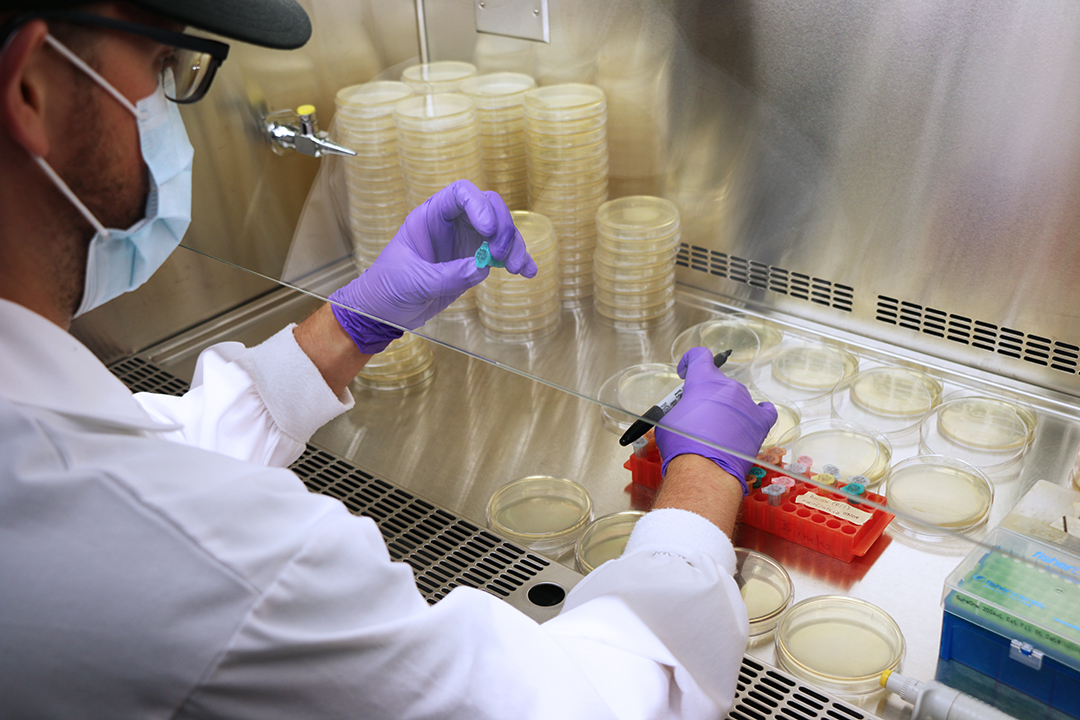

For that reason, the research team is developing a diagnostic tool that will enable beekeepers to detect spores in their honey so they can determine the risk of AFB developing in their yards and then decide the best way of managing and preventing the disease in their colonies.

The researchers are conducting ongoing surveillance of honey samples from beekeepers across Saskatchewan and are using their risk assessment tool to monitor spore levels so they can inform individual beekeepers of the AFB risk within their hives.

In addition to developing a diagnostic tool and analyzing honey samples, the researchers are also measuring the changes that occur in spore levels within honey samples once routine antibiotic treatment is stopped. By observing the impact of discontinuing treatment, the researchers can establish whether AFB can realistically be managed without antibiotics.

“We are tracking changes in spores in different parts of the hive over time and regularly inspecting the hives to determine how long of an interval we may expect between the last antibiotic treatment and the emergence of American foulbrood disease,” Zabrodski says.

Should this research reveal that spore counts don’t increase significantly when antibiotics are no longer used, those beekeepers classified as low risk for AFB may be able to stop or limit their use of antibiotics — as long as they continue assessing the risks and implement appropriate alternative management techniques. If antimicrobial use can be limited to those operations classed as a moderate or high risk, P. larvae will have fewer opportunities to develop any further antimicrobial resistance.

So far, the researchers have detected antibiotic-resistant isolates of P. larvae in a couple of surveillance samples collected from beekeeping operations across Saskatchewan. However, they’re optimistic that beekeepers can use their diagnostic tool and surveillance results to strengthen evidence-based management strategies that will decrease antibiotic use while keeping their bees healthy and thriving.

Although many diseases are treated with antimicrobials, AFB in honey bees is one that presents a significant challenge that needs to be countered with vigilant management techniques and strategic antibiotic usage.

“With growing international concern for antimicrobial resistance across both human and veterinary health, we need to be better with how we use antibiotics in any species, whether they be cattle, swine or honey bees,” says Zabrodski.

The Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund, Saskatchewan Beekeepers Development Commission, Mitacs, Project Apis m. Christi Heintz Memorial Scholarship, WCVM Interprovincial Graduate Student Fund and the Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars Program have provided financial support for the AFB studies.

Lara Reitsma of Victoria, B.C., is a third-year veterinary student at the WCVM who worked as a summer research student with the college’s honey bee health research group in 2021. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.