Why studying microbiology will make me a better veterinarian

When I tell people that I spent a summer working with bacteria rather than animals, I get puzzled looks and they often ask, “What does that have to do with being a vet?” The answer is simple: everything.

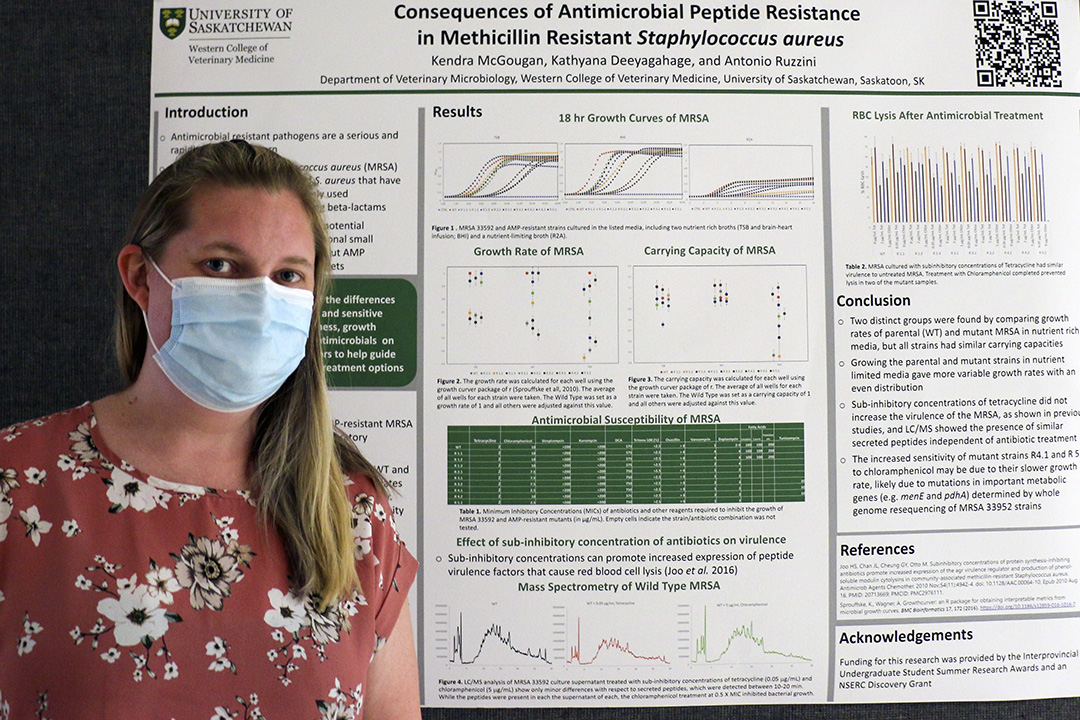

By Kendra McGougan

Although the COVID-19 pandemic made vet school different from anything I had pictured, it pushed me far outside of my comfort zone. I developed a keen interest in microbiology, especially in terms of examining disease outbreaks — how they occur and how an epidemic can suddenly become a pandemic.

As a result, I applied to become a Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) summer research student in 2021 so I could study microbiology with Dr. Tony Ruzzini, an assistant professor in the college’s Department of Veterinary Microbiology.

Since veterinarians must diagnose and treat disease appropriately for a wide range of animals, they often deal with pathogens (disease agents) that can present differently in different species. By understanding the characteristics and behaviour of pathogens, clinicians can easily identify the particular disease-causing organism to determine the most appropriate treatment.

“When we look at ways to treat or prevent diseases, we usually take the perspective of the host and focus on how the animal itself is affected,” says Dr. Joe Rubin, an associate professor and a veterinary microbiologist at the WCVM. “But if we don’t also look from the perspective of the pathogen, we’ve missed an entire piece of the puzzle.”

My summer research project focused on Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), a common Gram-positive bacterium that can colonize healthy individuals and lead to “opportunistic” infections. These are infections that develop when pathogens take advantage of an unusual situation such as a weakened immune system.

S. aureus infections can be contagious, passing between individuals through direct and indirect skin contact. As well, they often lead to extremely painful inflammatory diseases: bumblefoot in poultry, opportunistic infections in cats and dogs, and mastitis in cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and horses. Since S. aureus is well adapted to colonize mammals and can transcend species, pets such as cats and dogs often acquire the bacterial infection from their human companions.

This bacterial species is especially concerning for dairy cattle. S. aureus outbreaks often cause contagious mastitis that results in decreased milk production and devastating financial losses to cattle producers.

Although veterinarians usually treat S. aureus infections with penicillin, scientists are concerned that the bacterium will develop mutations so it can withstand traditional treatments — limiting treatment options.

A large component of my summer research was aimed at assessing the fitness and behaviour of two types of S. aureus strains — the drug-sensitive and the multi-drug-resistant type. While the drug-sensitive strains have genetic characteristics that ensure its survival in natural conditions, the multi-drug-resistant strains have undergone genetic mutations that have changed those characteristics.

To observe the variation of traits between strains, we grew the bacteria in various media (substances that support bacterial growth). Since the different kinds of media contain various types and quantities of nutrients, we could assess the nutritional requirements of each strain by observing its rate of growth and its maximum amount of growth as well as the factors that limit its growth.

We also compared potential treatments by observing their effects on each strain of S. aureus. For example, we looked at differences in the genomes of drug-sensitive and resistant strains and correlated mutations to the bacterias’ responses to various types and concentrations of antimicrobials, the alterations in bacterial growth patterns and virulence, and the microscopic structural changes in the bacteria that occurred after therapy.

This information can help scientists to predict how the bacteria will mutate in response to specific antimicrobials and to assess the potential for increased resistance as a result of different treatments.

“While antimicrobial resistance is a major concern, developing a better understanding [of] how resistant strains differ from those susceptible to antibiotics can provide insight into how to better address the problem and may reveal alternative drug targets or treatment strategies,” says Ruzzini.

Overuse and incorrect use of antibiotic drugs have contributed to this emerging problem of antimicrobial resistance. As a result, veterinarians need the knowledge base to recognize a variety of microscopic organisms so they can develop distinctive treatments that target each individual patient.

“Antimicrobial resistance is the under-recognized pandemic of our times. It's a slower burn than COVID-19 and our global response to this problem has been inadequate,” says Rubin. “The impact of resistance on the ability of veterinarians and physicians to treat their patients is increasing, resulting in more difficult or even impossible-to-treat infections.”

My summer research experience completely changed my perspective and my approach to disease management. Previously, my entire focus would have been the animal, and I would have concentrated on eliminating the disease as quickly and easily as possible.

However, now that I know the ways in which various treatments can influence bacterial behaviour, I’ll ensure that my treatments involve a two-fold approach that appropriately treats both the animal and the pathogen.

Kendra McGougan of Sooke, B.C., is a fourth-year veterinary student at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) who worked as a summer research student in 2021. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.