Changing my tune: from mezzo-soprano to student scientist

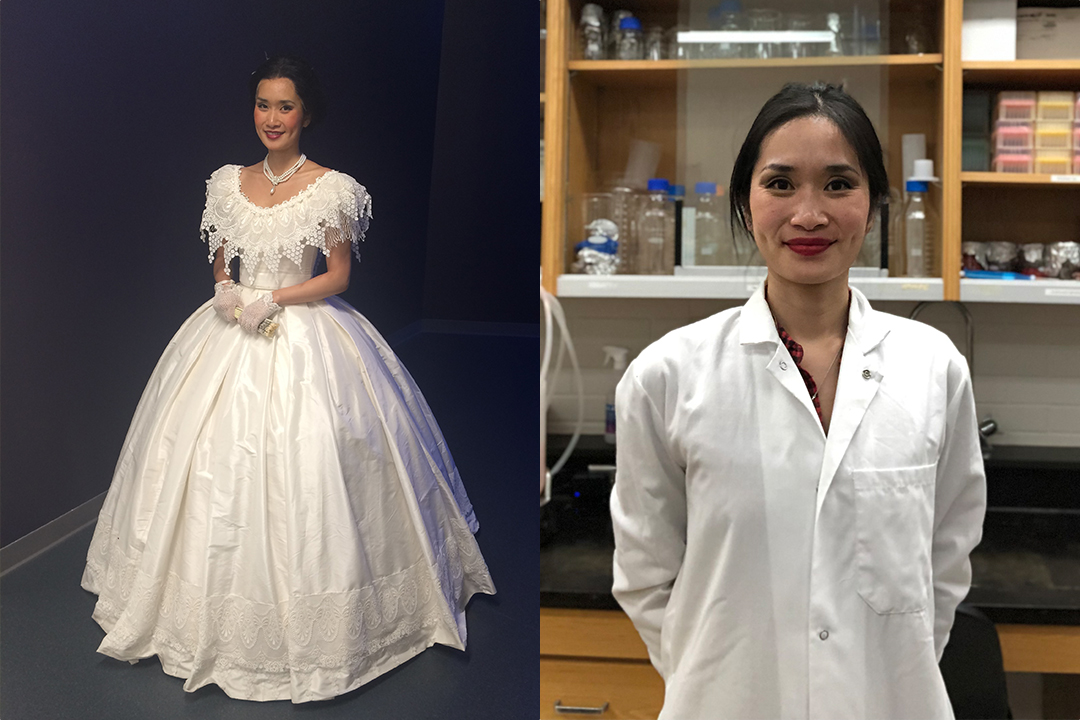

Two years ago, I traded in my evening gowns for a lab coat.

By Evanna Lai

Having been a professional opera singer for years before I made the pivotal decision to pursue veterinary medicine, I knew I would face challenges in my new career path. Other than the required science courses that I took — all online, due to the COVID-19 pandemic — I had very little experience collecting research data, working in a laboratory and writing scientific materials.

Last summer, following my first year of veterinary school at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), I decided to delve headlong into research. My research mentor was Dr. Suraj Unniappan, a WCVM professor and the University of Saskatchewan’s Centennial Enhancement Chair in Comparative Endocrinology. His research focus is the endocrine system — a collection of hormone-producing glands that regulate a wide range of biological processes in the body.

I was fortunate to receive a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) undergraduate student research award and support from the Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars program. As well, the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund provided partial funding for my summer research project.

My first week in the lab consisted of me cluelessly following my lab manager around as she patiently tried to explain the basics of laboratory techniques: RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and primer design and validation.

Research protocols that were familiar to most people with a science background were as strange to me as a brand new opera. It felt like cracking open the music score for Mozart’s Così fan tutte for the first time to learn one of the lead roles, Dorabella — a long journey of discipline and discovery.

Certainly, the learning processes for both have some striking similarities. Instead of translating operatic texts from a foreign language, I was looking up definitions for “myokine” and “type I transmembrane protein.” Practising a phrase of music over and over became pipetting substances into samples again and again — both actions cementing themselves into my muscle memory.

As with the rehearsal process, these laboratory techniques became less daunting with time and repetition. By the third week, I had successfully performed a primer validation — a standard lab procedure. I also began writing a review paper to familiarize myself with what I was researching. In small but crucial steps, I was laying the groundwork for myself to becoming a competent scientist.

My chosen project has a rather unassuming title: “Irisin: a survey in domestic animals.” Irisin is a recently discovered hormone that is strongly associated with exercise and energy use. While it has been widely studied in humans, we have yet to investigate irisin in many domestic species.

Our research focuses on comparing the presence and expression of irisin between different animal species, with the ultimate goal of establishing a foundation for further research on irisin in veterinary medicine.

We began our project by using computer modelling to determine the rate of conservation of the amino acid sequence for irisin between different species. This process gives us a clearer picture (evolutionarily speaking) of how irisin came to be in various animal species and supports the idea that irisin is an important hormone for mammalian life. Preliminary results largely showed a well-conserved sequence across mammalian species and even in some non-mammalian vertebrates such as birds, fish and snakes.

Over the summer, we used a couple of lab techniques — reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) — to determine the presence of irisin in both tissue and serum samples across various species. Then, we used immunohistochemistry (a technique for visualizing cellular components) to better visualize the distribution of this protein in our samples. While the immunohistochemistry trials still need to be refined, we accomplished all that we set out to do over the summer.

I chose this particular topic from a list of projects put together by WCVM professors seeking summer students to aid in their research. My choice was less guided by personal interest and more by the fact that I had appreciated Dr. Unniappan as a lecturer in our classes last year.

Yet, over the course of a steep learning curve, I gained a deeper appreciation for the widespread implications of irisin research. This humble hormone has now been linked to beneficial effects for the heart, skeleton, nervous system and metabolism. With more research developing in both people and animals, perhaps irisin may one day be useful as a therapeutic or diagnostic tool for various diseases.

As I became more comfortable and involved with collecting the data we need, my days became busier. Our pig sample processing was underway, and we had more samples come from ducks, horses, cats and dogs. While we had a preliminary survey of irisin in all of these species by the end of the summer, we couldn’t find any irisin sequences in invertebrates.

Our analysis opens the door to more questions, as good research tends to do. Does irisin function similarly in all mammals? Did invertebrate species evolve an analog (an alternative) to irisin or is it somehow unnecessary to them? Questions like these are fodder for future research projects.

If you had asked me two years ago if I could have imagined myself working in a lab, I would’ve laughed and written it off as a joke. But my summer of research showed me how flexible we can be if we allow ourselves the opportunity to explore new horizons and not be limited by our own expectations.

While I have stepped away from the operatic stage, I am constantly surprised to see how habits of diligence, creativity and commitment — so integral to performing artists — can also be indispensable for researchers. I hope to one day have as much facility with conducting a research project on my own as I do with learning, memorizing and performing Dorabella on stage.

Evanna Lai of Vancouver, B.C., is a third-year veterinary student at the WCVM who worked as a summer research student in 2022. Her story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students. Based on her summer research, Evanna is lead author on a paper published in Domestic Animal Endocrinology with a second paper under review at another peer-reviewed journal.