A rare reaction for a rare cat

My cat Bart is my best friend. When I’m sad, he jumps to where I am and lies down for pets and cuddles. He goes crazy for chicken liver cat treats. And when I come home from a long day at university, he greets me at the door.

By Cat ZensLast year, I adopted Bart from a local pet shelter when he was 15 months old. As a kitten, he had received his core vaccines — feline viral rhinotracheitis, calicivirus and panleukopenia (FVRCP) and rabies — with no reported issues.

When it came time for Bart’s annual vaccinations two months after his adoption, I took him to our local veterinarian. But soon after we left the clinic and came home, Bart began vomiting and having diarrhea. Shortly after, he started panting and his ordinarily high-pitched meow turned low and almost robotic.

I rushed Bart back to the local clinic for emergency care where the vet gave him antihistamines and steroids to treat his symptoms. He recovered within a few hours.

Adverse reactions to vaccines are reported in only half a per cent of cats, according to the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA). Bart became part of this very small statistic.

Dr. Karen Sheehan (DVM), a clinical associate at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine’s (WCVM) Veterinary Medical Centre, stresses that potential post-vaccination adverse effects are extremely rare and shouldn’t steer pet owners away from vaccinating their cats.

“Vaccines are always highly effective at preventing disease… they can be very lifesaving,” says Sheehan, who has seen fewer than 10 cases of post-vaccination adverse reaction in her 20-year career as a veterinarian.

So what happens when cats like Bart experience adverse reactions after vaccination?

“There was an overstimulation of Bart’s immune system which caused him to have an anaphylactic shock reaction,” says Sheehan.

Anaphylactic reactions trigger an animal’s shock organs, which are organs that may experience hypovolemic shock in critical cases. In cats, these organs are the lungs and skin. Anaphylactic reactions caused the side effects that Bart experienced — diarrhea, vomiting and heavy breathing.

Sheehan further explains that these types of side effects are described as “hypersensitive” or extreme sensitivities to specific substances: “It’s an overreaction of [the cat’s] own immune system.”

Allergic reactions are often the cause of post-vaccination adverse effects in cats. When I adopted Bart, the rescue organization’s representative mentioned that he had allergies — but no one knew what specifically caused them.

Sheehan says that anaphylactic reactions become more severe the more an animal is exposed to the substance they are allergic to, pointing to peanut allergies in humans as an example.

“Sometimes the more times you’re exposed to something is when you’re going to develop an anaphylactic reaction, meaning that you won’t automatically have a severe adverse reaction to peanuts the first time,” Sheehan says.

“If you take it again, or eat it again, or get exposed to it again [allergens], then those reactions are going to get heightened each time.”

But whether Bart’s reaction was because of his potential allergies isn’t known for certain.

Sheehan says another cause for post-vaccination reactions in cats is the immune system getting overwhelmed from receiving more than one vaccination at one time.

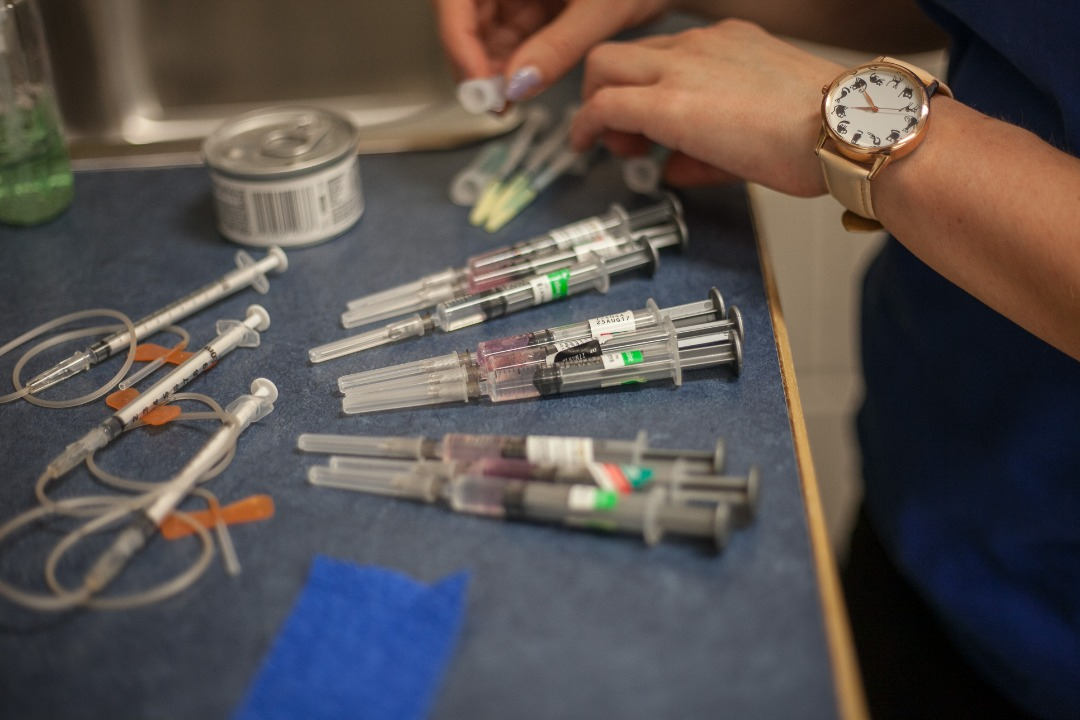

Bart was vaccinated for FVRCP, rabies, and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) in one day. FVRCP and rabies are considered core vaccines for all cats, while FeLV vaccines are core for kittens under the age of one.

Exposure to these three vaccines at once may make some animals more prone to side effects, although this is still incredibly rare.

“When [veterinarians] give multiple vaccines, it’s very difficult for owners to get their cats vaccinated in three separate appointments,” Sheehan says. “Sometimes what happens is we’re more likely to have an anaphylactic reaction when we give [multiple vaccines during the same appointment].”

In rare cases, cats can also develop a form of cancer at their injection sites called injection site sarcoma. This cancer can develop after about one in 10,000 injections (including non-vaccine injections such as microchipping procedures). Although its causes are relatively unknown, Sheehan says veterinarians believe genetic makeup contributes to cancer development.

Sheehan says veterinarians are trained to perform injections below the cat’s limb, so if cancer occurs, they can amputate the limb to prevent the chances of the cancer spreading to other organs.

Sheehan reiterates that cats are much more at risk from deadly diseases such as FeLV — diseases that can be prevented through vaccination — in comparison to these rare conditions.

She notes that in cases like Bart’s — in which cats have experienced previous anaphylactic reactions — pet owners should speak with their veterinarians about what vaccine-related strategies to take.

“I would never give multiple vaccines at one time if [the animal] had a previous reaction,” she says. “And I would be choosing what vaccines need to continue to be administered.”

Sheehan adds that veterinarians can give cats antihistamine medication before they are vaccinated to fight off allergens.

If animal owners have questions about potential anaphylactic reactions after vaccinations, Sheehan recommends that they talk to their local veterinarian. As well, they can also visit the American Veterinary Medical Association’s web site for more information and resources.

Cat Zens of North Battleford, Sask., is a fourth-year student in the University of Regina’s School of Journalism. She is working as a research communications intern at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) for summer 2023.