With help from pigs, USask scientists strive to expedite organ transplant process

Researchers have made progress in improving human organ transplants in Canada over recent years, but it’s far from perfect.

By Cat ZensFinding compatible organ donors for patients outside of their own families is still incredibly challenging. As for patients who need transplants of the heart or other single organs, they’re reliant on organ donations — but only a fraction of Canada’s population registers for the national organ donation program.

As well, less than half of 30,000 organ graft recipients live any longer than 10 to 15 years with a functioning graft.

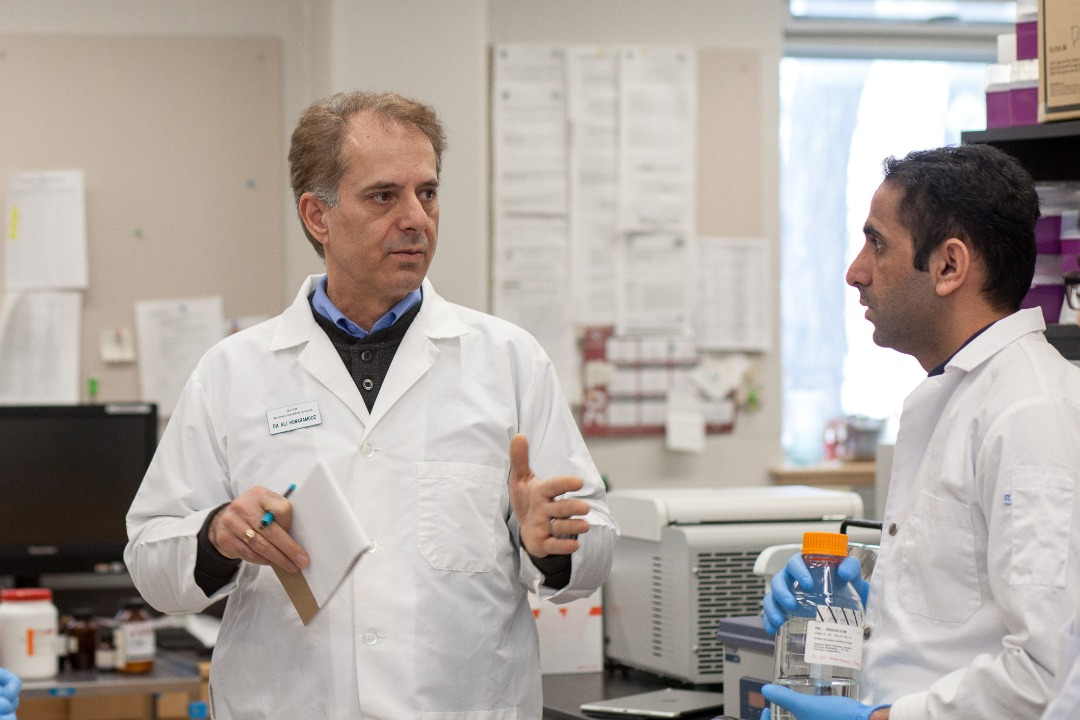

As a solution to Canada’s ongoing organ shortage crisis, biomedical scientists such as Dr. Ali Honaramooz (DVM, PhD) at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) are looking to xenotransplantation (organ transfers from animals to humans). Specifically, Honaramooz and his postdoctoral fellow, Dr. Fahar Ibtisham (PhD), are investigating the use of pig organs for human transplants.

Scientists prefer pigs for xenotransplantation because the animal species can be bred easily, and it only takes about six months for pigs to reach a mature size. Pigs and humans also have compatible body sizes and share similar physiological and pathological traits such as similarities in organ placements and functions.

Honaramooz and Ibtisham are studying an alternative approach for producing transgenic (genetically modified) pigs by transplanting genetically modified stem cells in the pig’s testis.

“The whole organ transplant waiting list is already long enough. But the demand will be much higher as soon as a more effective way of providing suitable organs is available. You can imagine many more people would be prime candidates to receive organs from transgenic pigs,” said Honaramooz, a professor at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).

The original method of producing transgenic pigs involved manipulation of early eggs and embryos. For this process, researchers insert a desired gene into a porcine egg (or ovum) and transfer it into the uterus of a surrogate pig. Another current method is cloning, which replaces a porcine embryo’s genes with genetically modified genes of another cell.

However, both methods have known limitations. These procedures take a long time and can cause potential developmental issues in the pig.

In the new method that Honaramooz’s research team has developed, researchers castrate male pigs and separate the testis stem cells in the lab. The next step is for researchers to make the desired changes in the genome of the pigs’ stem cells. Within a few hours, the researchers can inject these stem cells into other pigs’ testes. This process creates a faster way to develop genetically modified sperm, allowing transgenic pigs to be produced quickly and efficiently.

“Because stem cells are able to make more of themselves through this process … in a way you have permanently changed the way sperm is produced in that animal,” said Honaramooz. “They become transgenic sperm-producing pigs. In other words, it takes only three months to have the transgenic sperm produced instead of a year.”

Honaramooz’s research team is planning to conduct this process using CRISPR technology, a genome editing system that allows scientists to modify the genome and edit parts of DNA quickly and orderly.

“You can make many different changes to the genome all at once [with CRISPR technology], and that’s very powerful. And day by day, there are advances in genome editing technology that allows us to modify the genome much easier,” Honaramooz said.

The WCVM researchers’ goal is to create a quick, alternative way of developing pig organs for transplantation, which would help to improve organ transplant waiting lists in Canada. They aim to do this in a biosecure way that prevents zoonotic diseases (illnesses that can be transmitted from animals to humans) from developing in pigs’ organs.

“We’re hoping to have our first transgenic pigs within a few years. It’s an exciting time because if everything goes well … we have a shorter way of reaching that goal.”

Honaramooz’s research team received $10,000 from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation’s (SHRF) Align Grant program, which supports Saskatchewan-related human health studies.

In addition to SHRF, the Government of Saskatchewan and USask have also assisted with funding for this project to help pay Ibtisham’s salary as a postdoctoral fellow.

Honaramooz hopes to continue to receive funding for this research in aims of hiring more researchers and having more access to scientific equipment and resources.

“This is expensive research so I hope that with additional funding, we get to our objective in near future.”

Cat Zens of North Battleford, Sask., is a fourth-year student in the University of Regina’s School of Journalism. She is working as a research communications intern at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) for summer 2023.