USask veterinary researchers build tumour bank to advance cancer research

Everyone knows the deadly disease that is cancer, but ironically, what makes cancer so deadly is how little is known about it.

By Eric Kim

This summer, I worked at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) with Dr. Arata Matsuyama (DVM, PhD), a specialist in veterinary medical oncology at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), and Dr. Behzad Toosi (DVM, PhD), an assistant professor and the WCVM’s Allard Research Chair in Oncology, to help learn more about cancer through a comparative oncology study.

Our work focused on building a “bank” of tumours sampled from dogs and cats with the goal of establishing a knowledge base of various cancer types for both animals and humans.

“Comparative oncology aims to help researchers better understand the biology of cancer. We hope to find new treatments for both humans and animals by studying naturally occurring cancers in pets,” says Matsuyama, an assistant professor in the WCVM’s Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences.

He adds that this area of research acts as “a stepping-stone” between humans and animals — two very different, yet surprisingly similar species in the genetic and molecular mechanisms of cancer formation.

The tumour bank program will provide three main benefits for future researchers: quick and easy access to the bank, samples from over 20 different cancer types thus far, and a high volume of samples representing each cancer type.

“The tumour bank will help advance veterinary oncology research, thereby expanding the data available with which comparative oncology can be pursued,” says Matsuyama.

“This will have important implications in identifying the genetic cause of different cancers and for finding the potential of improving the diagnosis and therapy of these cancers. That is the ultimate goal of our research.”

The first step of the tumour sampling process is to screen for patients that have tumours greater than three by three centimetres in size. We then ask the pets’ owners for signed consent stating that they volunteer tumour tissue from their animals. After we have permission, the specific procedure for collecting the sample depends on the stage of the patient’s cancer assessment.

If the patient’s tumour and the surrounding tissue has already been removed by surgery, we collect a small sample (less than a quarter of the mass). If veterinarians need to take a tumour biopsy for diagnosing the cancer, they remove a small piece of tumour tissue during a minor surgical procedure while the patient is under sedation or general anesthesia. From this biopsy sample, we can collect a small sample.

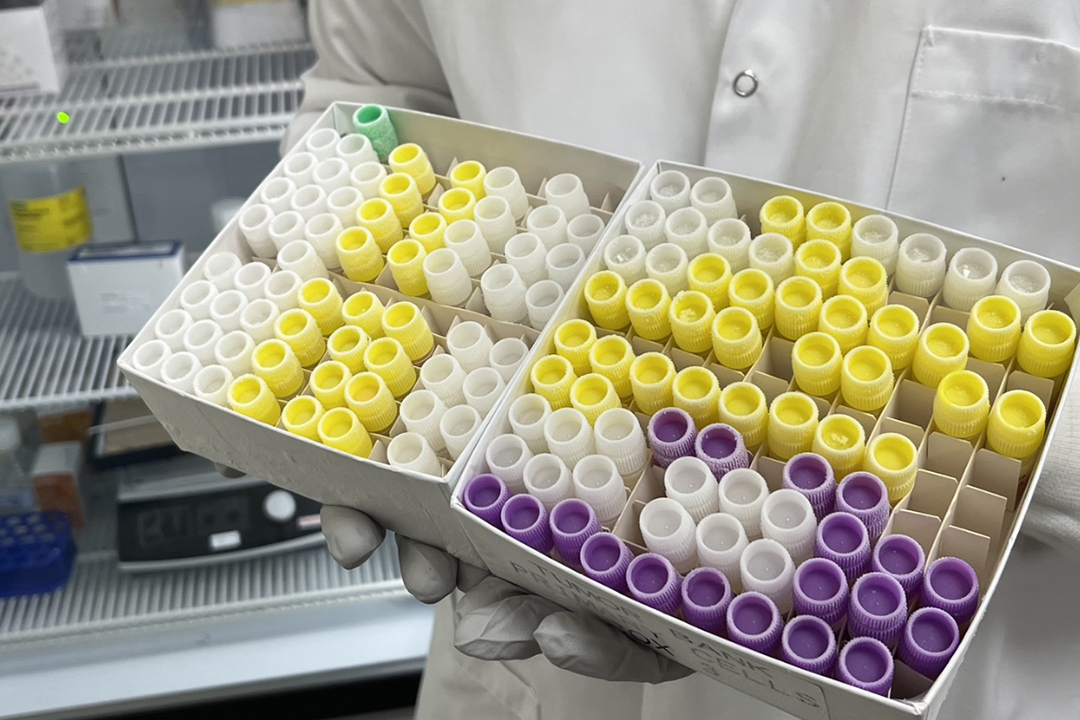

Since the project began in the fall of 2022, WCVM oncologists have collected over 50 tumour samples of 20 different tumour types collected from individual patients. In addition, cell lines from 25 tumour samples have been isolated and stored in the bank. The number of banked tumour samples is increasing by an average of one to two samples each week — meaning that the WCVM could have over 150 tumour samples banked by the end of 2024.

The WCVM uses several methods to store the tissue samples:

- the tumour cells are separated from the tissue using a sterile method to grow and purify in a special environment.

- small tumour pieces are placed in formalin and then encased in paraffin to preserve their original structure for a long time

- another set of tumour pieces are rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen.

- some samples are placed in a special solution called “RNAlater” to keep the genes well preserved

These storage methods allow various types of tissue samples from the same patient to be available, while also being integral in the cell line identification process. Used extensively in research as models of normal and cancer tissues, a cell line is a collection of cells that originally came from one cell. Identifying or authenticating a cell line ensures that it’s correctly identified and not cross contaminated with other cells.

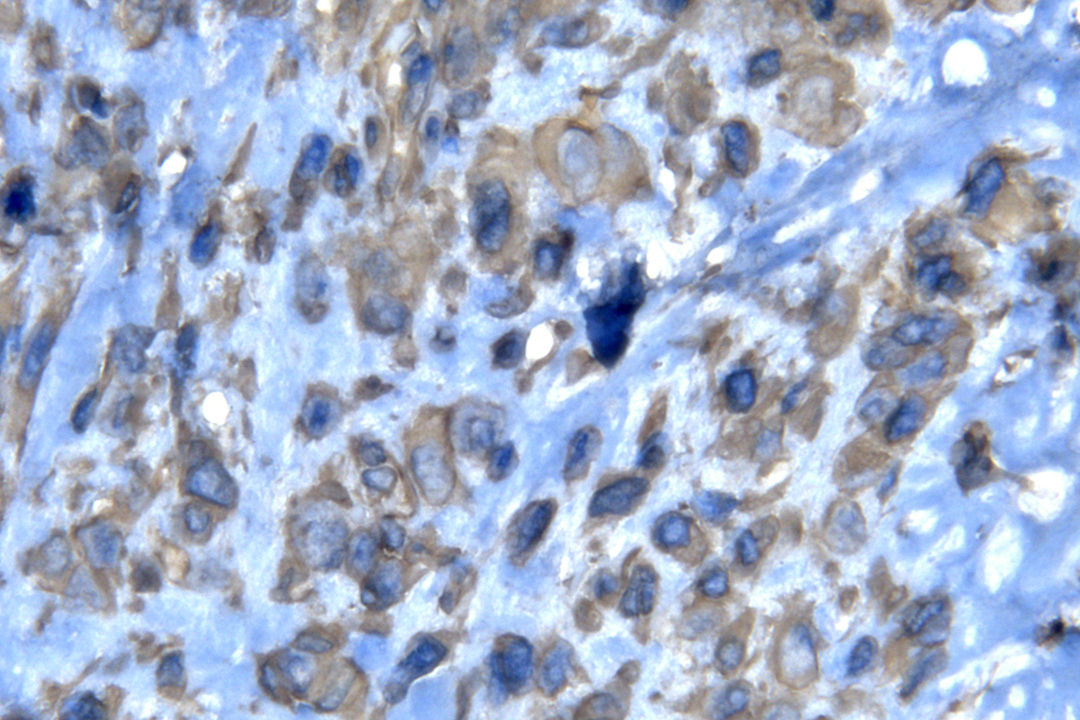

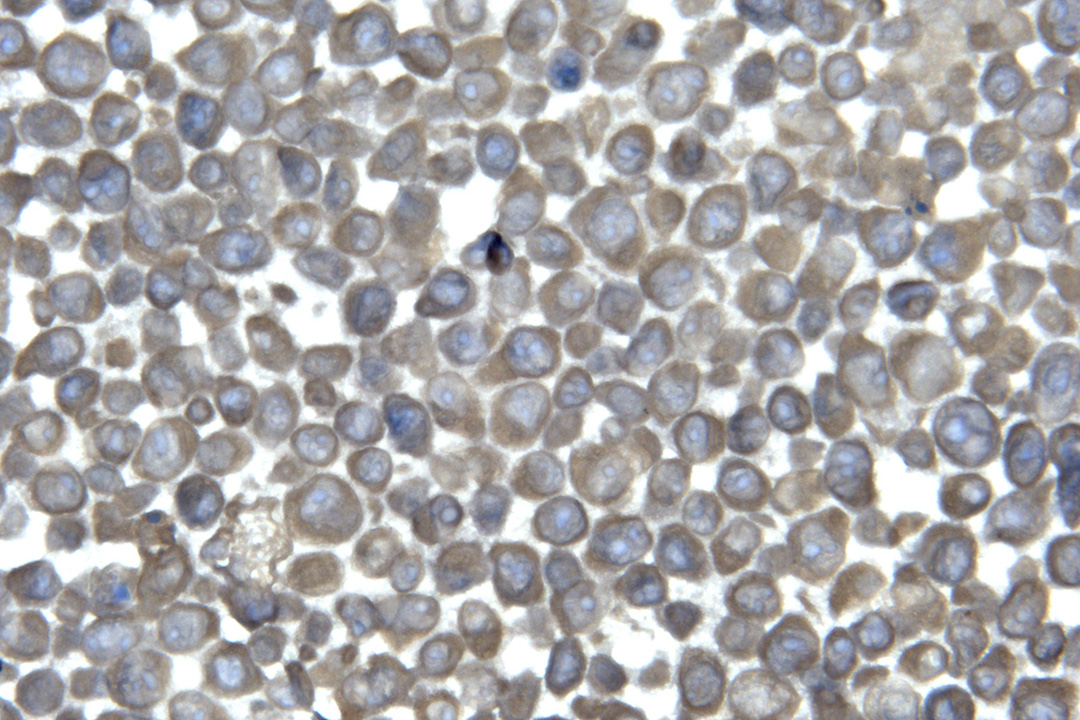

As a first step in the tumour bank’s development, the WCVM research team is focusing on analyzing three tumour types: osteosarcoma, pulmonary carcinoma and soft tissue sarcoma in dogs. The team is characterizing tumour cells, which are isolated aseptically (free from any disease-causing organisms) and cultured, using two methods.

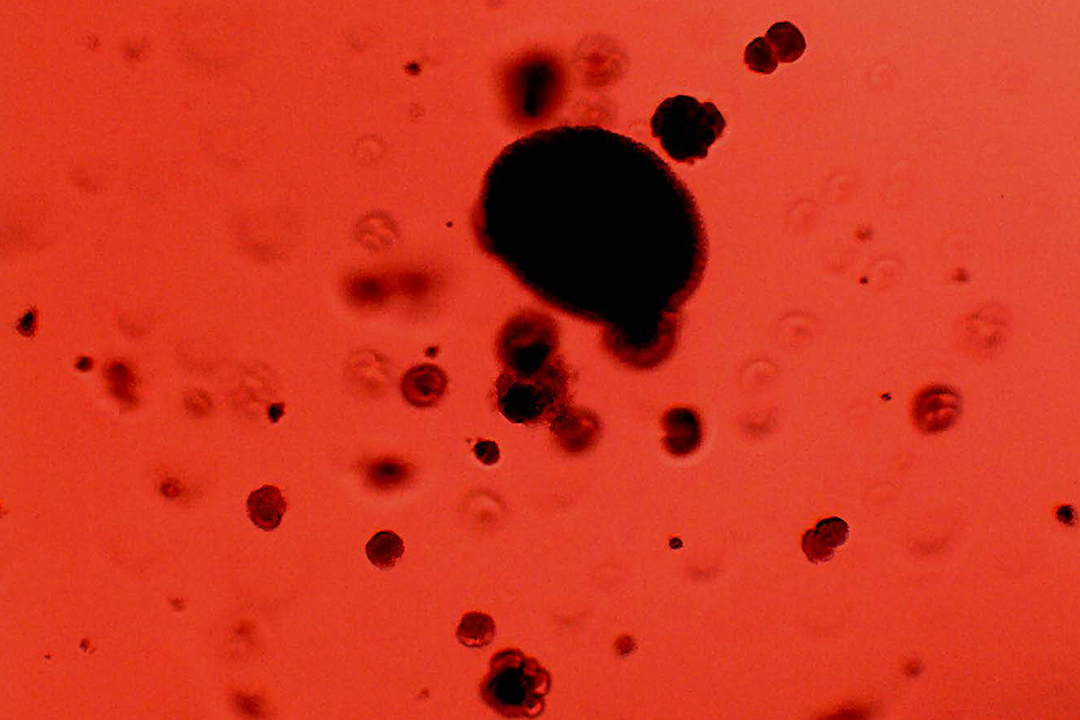

Immunohistochemistry uses antibodies to confirm the protein expression profile of the samples and cancerous origin of the isolated cells. A second method, soft agar colony formation assay (SACFA), predicts the degree of malignancy or aggressiveness of the tumour from which the cells were isolated from.

The WCVM is now the second veterinary college in Canada to have a veterinary tumour bank, apart from the Ontario Veterinary College at the University of Guelph. This not only means a potential boost in cancer research funds, but it will allow the WCVM to be among the leaders in Canadian veterinary oncology — playing a significant role in advancing comparative oncology.

Cancer has had an impact on all our lives in one way or another. Taking part in initiating WCVM’s tumour bank was a privilege, and I feel that I have made a significant and lasting contribution to future comparative oncology research as we inch closer to fully understanding this disease for both humans and animals.

The WCVM Companion Animal Health Fund (CAHF) has provided funding for this research project.

Eric Kim of Coquitlam, B.C., is a third-year veterinary student at the WCVM. His story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students. Kim earned first place in the clinical and applied research category at the WCVM's 2023 undergraduate student research poster day for his summer research work on the WCVM's tumour bank project.

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.