BIG project requires a large and diverse team

What do a veterinarian, an ecologist, a virologist, a conservation officer and a structural engineer-turned-veterinary-student have in common? They are all vital members of a diverse team that’s working toward the conservation of Canada’s once-great bison herds.

By Chris JamesFunded by Genome Canada, the Bison Integrated Genomics (BIG) Project is a multi-stakeholder initiative that’s working to ensure the long-term genetic diversity of Canada’s bison herds while protecting genetically pure bison.

The project participants include people from a variety of backgrounds: veterinarians, biologists, ecologists, engineers, Parks Canada conservation officers, graduate students and experts in semen cryopreservation and in vitro fertilization.

“The most amazing thing about this project is that we have such a convergence of expertise — the most amazing convergence that I’ve seen in my 30-year career,” says Dr. Gregg Adams (DVM, PhD). The veterinarian and reproduction specialist is a University of Saskatchewan (USask) professor at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) as well as co-leader of the BIG project.

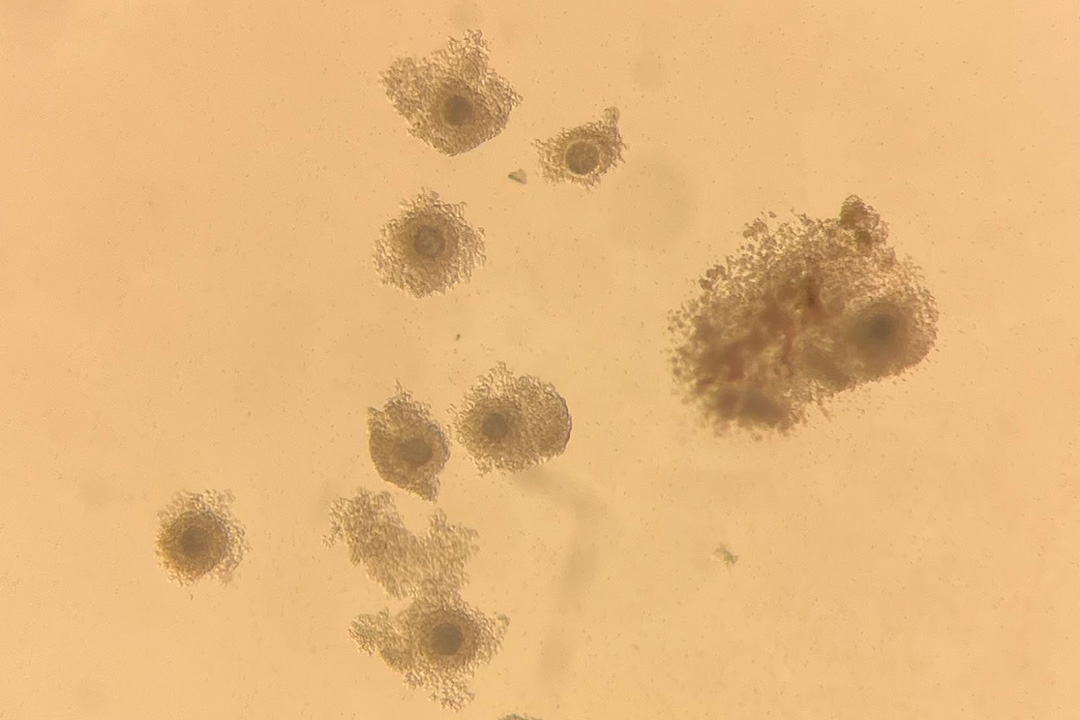

One of the project’s tasks is rescuing and transferring healthy germplasm (sperm and eggs) between wild and genetically depauperate herds. But to achieve this goal, scientists must often work in remote environments during cold months. To complicate matters, temperature shock decreases the quality of the germplasm samples that are collected.

That’s where I became involved. Last summer, my research involved modifying the existing collection equipment so it could protect the samples from exposure to large temperature fluctuations.

I’m a third-year veterinary student at the WCVM, but before I began my veterinary studies, I trained and worked as a structural engineer. I had never expected my engineering skills to apply to veterinary medicine, but I used many of them last summer – skills such as problem solving, attention to minute details, precise workmanship, and even math and physics.

My research team developed a system for insulating the collection apparatus to ensure that the collected samples remained at prescribed temperatures with minimal fluctuations, even in a remote setting.

While this task may seem simple, we had to overcome a multitude of constraints. We had to be able to observe the sample collection, the temperature buffer system had to be lightweight and maneuverable, the equipment needed to withstand transportation by truck or helicopter to a remote area, and the collection apparatus had to be easy to assemble in a field setting.

Last summer, I had the chance to join the group that was field testing our equipment modifications. During a week-long trip to Elk Island National Park, located east of Edmonton, Alta., our diverse team collected germplasm from chemically immobilized wild bison.

The germplasm collections started out like a game of cat and mouse. But in this case, the “cat” was a truck containing a veterinarian and a support team while the “mouse” was a majestic wood bison weighing nearly 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds).

The process began with the truck slowly stalking its prey, inching through the tall grass so as not to spook the bison. Once the team was within range, then BANG — the veterinarian fired a dart loaded with an anesthetic drug into the thick muscles of the bison’s hind leg.

After the bison had settled into a deep sleep, the researchers waved in the second truck containing our collection team and the equipment. As we approached the immobilized bison, I could feel my heart rate rising. We quietly repositioned the animal, set up our equipment and collected the samples. When we finished, we packed up our equipment just as quietly as before, and we backed the truck away while the veterinarian administered a reversal agent to the sleeping animal.

Once we were a safe distance away, we sat in the back of the truck and recorded data from the collection and waited for “sleeping beauty” to awaken. Just as quickly as it dropped to the ground, the bison stood up with a slight wobble and then sauntered away to rejoin its herd.

Spending a summer working on this project has instilled in me the value of a team that applies the expertise of individuals with so many diverse specialties — and that’s of particular importance for an initiative with a scope as large as that of the BIG project.

Without everyone’s unique skills, a project of this size wouldn’t be possible. Just as each cable in a suspension bridge has an important job to do, every individual involved in the BIG project is crucial to its overall success and to the conservation of Canada’s bison herds.

Chris James of Grand Prairie, Alta., is a third-year veterinary student at the WCVM who worked as a summer research student in 2023. His story is part of a series of articles written by WCVM summer research students.