New veterinary program aims to support Canadian swine industry shortages

Nearly a decade ago, Dr. John Harding (DVM) noticed an alarming trend across Canada. As the country’s swine veterinarians grew older and reached retirement age, the number of young veterinarians interested in taking their place in the swine industry was dwindling.

By Tyler SchroederPhoto: Roman Nosach.

“There was a realization that we needed to change our approach to training swine veterinarians,” says Harding, a professor, researcher and swine practitioner at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).

Veterinarians who specialize in swine health management play a critical role in Canada’s swine industry — the country’s fourth largest farming sector. According to the Canadian Pork Council, more than 7,000 pig farms produce over 25.5 million animals each year with annual direct farm gate sales of $4.1 billion.

Swine veterinarians work closely with producers in managing herd health through disease prevention and biosecurity protocols that are in place to protect the industry from the threats of major disease outbreaks.

“We’re having a hard time attracting students to the swine sector. A major part of that is because there isn’t much exposure in this area of veterinary medicine,” says Harding.

After nearly five years of planning, the Swine Medicine Advancement, Recruitment and Training (SMART) program was fully launched in July 2024 with the support of Canada’s pork industry, swine veterinarians from across the country, and the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

As Harding explains, the SMART program is built on four pillars that address core industry concerns: attracting veterinary students to the industry, assisting in core competency development, enabling foreign-trained veterinarians to achieve licensure, and building continued education opportunities for veterinary professionals.

Attracting students in Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) studies was Harding’s key focus when he first explored the idea of building the comprehensive program five years ago.

“Undergraduate students aren’t exposed to the swine industry and there’s a lack of education in the general understanding of pigs and the profession,” says Harding. “I had discussions with other veterinarians and industry professionals to brainstorm what we could do about this.”

In response, Harding set up the Pharmhouse Summer DVM Student Swine Experience Program in 2020, which offered WCVM veterinary students an opportunity to gain hands-on experience working in swine medicine over a 12-week summer term. Students worked alongside swine veterinarians and in pork production units, as well as being introduced to swine research projects during their work placements.

“We promoted the program to first- and second-year students in lectures and classes. We were having some success, but we knew that other parts of Canada could benefit from this project, and we wanted to branch out,” he says.

Harding collaborated with his colleagues at the Ontario Veterinary College (OVC) and Atlantic Veterinary College (AVC) who were supportive in his plan to expand the student swine experience program to a national level in 2024. Bill Maxwell and his business, Pharmhouse Consulting, donated the funds that allowed this program to become a nationwide endeavour.

To help recruit students to the Pharmhouse program, Harding and some of his swine veterinary colleagues developed education seminars in 2024 as a recruitment tool.

“No student is going to sign up for a summer experience program in swine medicine if they don’t understand pigs or the industry. So, we started a seminar series called ‘Pig-Talks’ that starts with a basic overview of pigs, swine production, disease case reports and what veterinary careers in this industry actually look like,” says Harding.

“I think that providing students with this information is a key part of building interest.”

In 2024, four veterinary students from AVC, OVC and WCVM worked in swine practices located in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and Manitoba. All the students received a competitive wage — 60 per cent paid by the host veterinary practice and 40 per cent paid through the SMART program.

Heidi Rauser, a second-year veterinary student from Beausejour, Man., was one of two WCVM students to take part in the program. Her program placement was at PremierSHP, a swine veterinary business in Steinbach, Man., that offers clinical services in addition to production and research consultancy.

“Many people think that swine veterinarians are primarily tasked with paperwork. But there’s actually a lot of hands-on work involved,” says Rauser, who gained a range of valuable experiences during her three-month term.

Four weeks of her program were dedicated to working with swine veterinarians in swine barns through each stage of production — breeding management, farrowing and finishing pigs for market. During the rest of her work experience, Rauser was part of a research project studying the survival rates of lean piglets that received advanced care with glucose supplements and hygiene powders. Rauser also shadowed veterinarians on service calls and daily tasks at the facility.

“Herd health was a major part of my involvement. We’d do walk-throughs in the barns and analyze the temperature, air quality and airflow of the building and then monitor the health of the piglets and sows.”

These types of clinical activities are the focus of the SMART program’s second pillar. Harding has built a clinical competencies package that details activities involved in swine practice, providing both trainees and mentors with a practical tool they can use to track their training progress.

“There are 97 activities that are categorized by topic and levels of difficulty, and so it gives our trainees a structured guide to the work. It’s also a way to audit the learning process. Mentors can grade trainees on a scale system and evaluate their competencies, which is very valuable feedback,” he says.

Rauser’s time at PremierSHP has given her a positive outlook on opportunities in the industry.

“I can’t say for certain, but this summer has definitely opened my mind up to the possibility of pursuing swine medicine. For anyone who is interested in swine medicine, I’d highly recommend applying for the program.”

The third pillar of the SMART program highlights the foreign-trained veterinarian swine residency certification program. This initiative received financial support from three provincial pork boards (Alberta Pork, Sask Pork and Manitoba Pork) as well as the Western Canadian Swine Health Alliance that includes six of Western Canada’s largest pork producers — Sunterra Farms, Sunhaven Farms, Olymel, HyLife, Progressive Group and Maple Leaf Foods.

“These groups were instrumental in making our plan come to life and their financial backing helped to mobilize this project,” says Harding. “Their generosity was recently matched by federal research funding from the Mitacs Accelerate and NSERC (Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada) Alliance programs, which gave us a huge boost to the program.”

The three-year clinical residency program recruits veterinarians with degrees from non-accredited veterinary colleges and supports their re-training with the goal of achieving certification as a specialist in swine health management with the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners (ABVP).

“Instead of going to great lengths in recruiting new veterinarians into this industry, why not recruit and re-tool those who already have an interest in swine medicine? It’s a lot more efficient and there’s a lot of value in using their experience that they’ve already gained,” says Harding.

Formal residency training is completed remotely in rural swine practices, with clinical co-supervision provided by approved swine veterinarians. Academic training — including formal courses and research — are supervised by Harding using the WCVM and industry resources. The newly designed program is designed to upgrade the veterinarians’ knowledge and credentials so they can practise swine medicine in Western Canada.

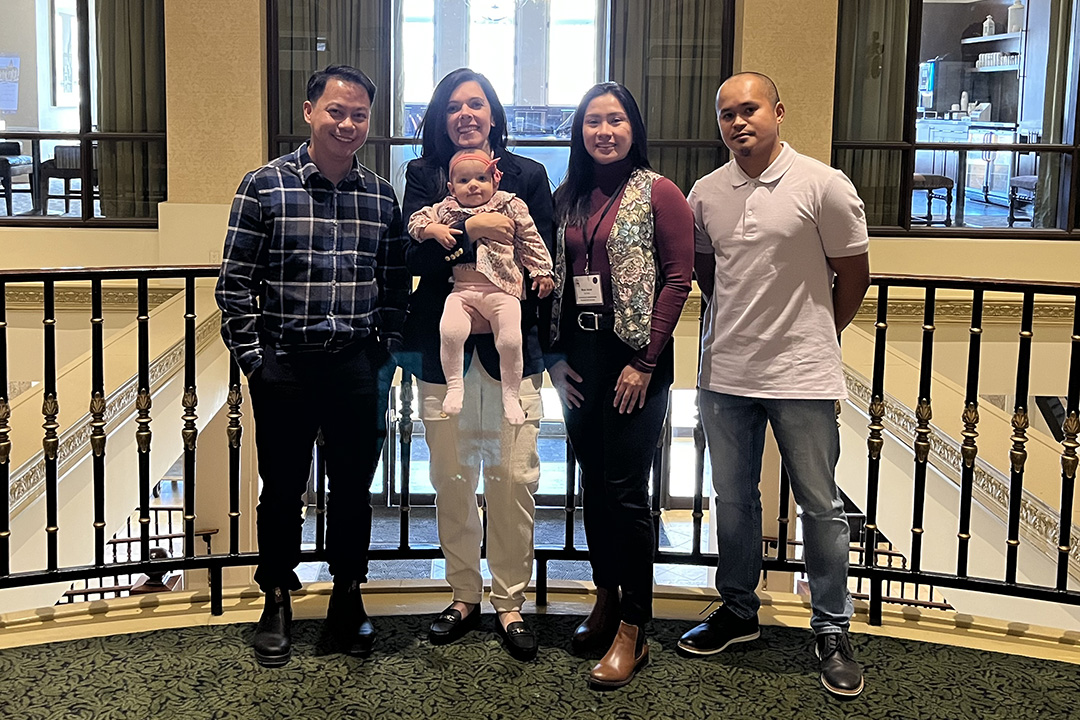

The first cohort, which started in July 2024, includes four residents who received veterinary degrees from the Philippines and Brazil. Four more potential positions are open for the right candidates.

“Over the three years, they’ll be gradually taking on responsibilities ranging from technical activities to herd health visits. In addition to the clinical training, they’ll complete a project-based Master of Science (MSc) degree and complete a research project on the topic of benchmarking and reducing mortality rates on swine farms in the Western Canada,” says Harding. “This all leads to writing the final ABVP certification exams, and if successful, they will be eligible to work as swine veterinarians in Manitoba, Saskatchewan or Alberta.”

The fourth pillar of SMART highlights continuing education (CE) and mentorship for swine veterinarians. In 2023, members of the Canadian Association of Swine Veterinarians (CASV) took part in a journal club that offered readings on swine industry-focused topics including swine production, animal welfare and biosecurity during the 16 sessions.

Harding hopes to maintain the momentum that the program has built up to this point and is optimistic that the program will be sustainable into the future.

“Our industry partners have funded this entire project. We’re very grateful and encouraged by the generosity of the provincial pork boards in Western Canada as well as the Western Canadian Swine Health Alliance in getting us up and running,” says Harding.

“It takes one guy to lead the charge, but it takes a whole army to make it work. I’ve been fortunate to receive a lot of internal support in getting this program up and running, but also to have industry backers is vital because they’re the ones that are funding the entire operation.”

Together we will support and inspire students to succeed. We invite you to join by supporting current and future students' needs at USask.