Potentially toxic chemicals from LCDs in nearly half of household dust samples tested: USask-led study

Chemicals commonly used in smartphone, television, and computer displays were found to be potentially toxic and present in nearly half of dozens of samples of household dust collected by a team of toxicologists led by the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

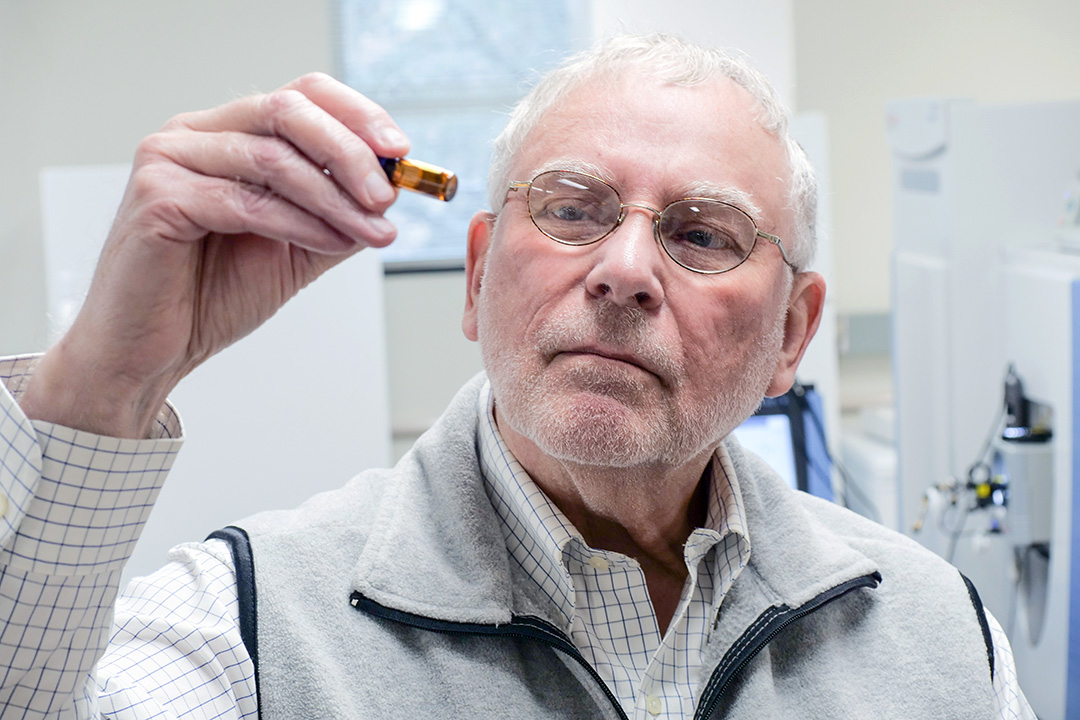

By USask Research Profile and ImpactThe international research team, led by USask environmental toxicologist John Giesy, is sounding the alarm about liquid crystal monomers—the chemical building blocks of everything from flat screen TVs to solar panels—and the potential threat they pose to humans and the environment.

“These chemicals are semi-liquid and can get into the environment at any time during manufacturing and recycling, and they are vaporized during burning. Now we also know that these chemicals are being released by products just by using them,” said Giesy, Canada Research Chair in Environmental Toxicology at USask.

“We don’t know yet whether this a problem, but we do know that people are being exposed, and these chemicals have the potential to cause adverse effects,” said Giesy.

In a first-of-its-kind paper published Dec. 9 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Giesy’s research team assembled and analyzed a comprehensive list of 362 commonly used liquid crystal monomers gathered from 10 different industries and examined each chemical for its potential toxicity.

The team also further tested the toxicity of monomers commonly found in six frequently used smartphone models.

The researchers found the specific monomers isolated from the smartphones were potentially hazardous to animals and the environment. In lab testing, the chemicals were found to have properties known to inhibit animals’ ability to digest nutrients and to disrupt the proper functioning of the gallbladder and thyroid—similar to dioxins and flame retardants which are known to cause toxic effects in humans and wildlife.

To understand how common these monomers are in the environment, researchers tested dust gathered from seven different buildings in China—a canteen, student dormitory, teaching building, hotel, personal residence, lab, and electronics repair facility. Nearly half of the 53 samples tested positive for the liquid crystal monomers.

“Ours is the first paper to list all of the liquid crystal monomers in use and assess their potential to be released and cause toxic effects,” said Giesy. “We looked at over 300 different chemicals and found that nearly 100 have significant potential to cause toxicity.”

Ninety per cent of the monomers tested had concerning chemical properties. They either accumulate in organisms, resist degradation in the environment, or are easily transported long distances in the atmosphere. Nearly one quarter of the chemicals tested had all three troubling characteristics.

“There are currently no standards for quantifying these chemicals, and no regulatory standards,” said Giesy. “We are at ground zero.”

Researchers Huijun Su, Shaobo Shi, Ming Zhu, and Guanyong Su of China’s Nanjing University of Science and Technology, along with Doug Crump and Robert Letcher of Environment and Climate Change Canada, worked with Giesy to conduct the research. Guanyong Su, who leads the research effort in China, was a former student with Giesy at USask and then a post-doctoral fellow with Environment Canada.

LCD panels are almost exclusively produced in three Asian countries: China, Japan, and South Korea. It’s estimated that 198 million square metres of liquid crystal display were produced last year—enough to cover the entire Caribbean island of Aruba.

“Since there are more and more of these devices being made, there’s a higher chance of them getting into the environment,” said Giesy.

For many years, huge amounts of globally produced e-waste—including LCD displays—have been dismantled, disposed of, and introduced into the environment.

“Right now, there are no measurements of these monomers in surface waters. Our next steps are to understand the fate and effect of these chemicals in the environment,” said Giesy.

In his previous work, Giesy was also the first researcher to identify that toxic perfluorinated and polyfluorinated chemicals were widespread in contaminating the environment. His research ultimately resulted in the entire class of chemicals being banned globally.

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, other Chinese research funding programs, and Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Giesy, professor at the USask Toxicology Centre, was also supported by a Distinguished Visiting Professorship in the environmental sciences department of Baylor University, Waco, Texas, U.S.

The paper including funding details is available here: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915322116

Article re-posted on .

View original article.