Veterinary students from 'then and now' compare notes during panel discussion

What was it like to be a veterinary student in the 1960s compared to students today at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM)?

By Rigel SmithThat general question served as the premise of “Vet med: then and now,” a unique panel discussion held during Vetavision — the WCVM’s student-organized public open house that took place in September 2024.

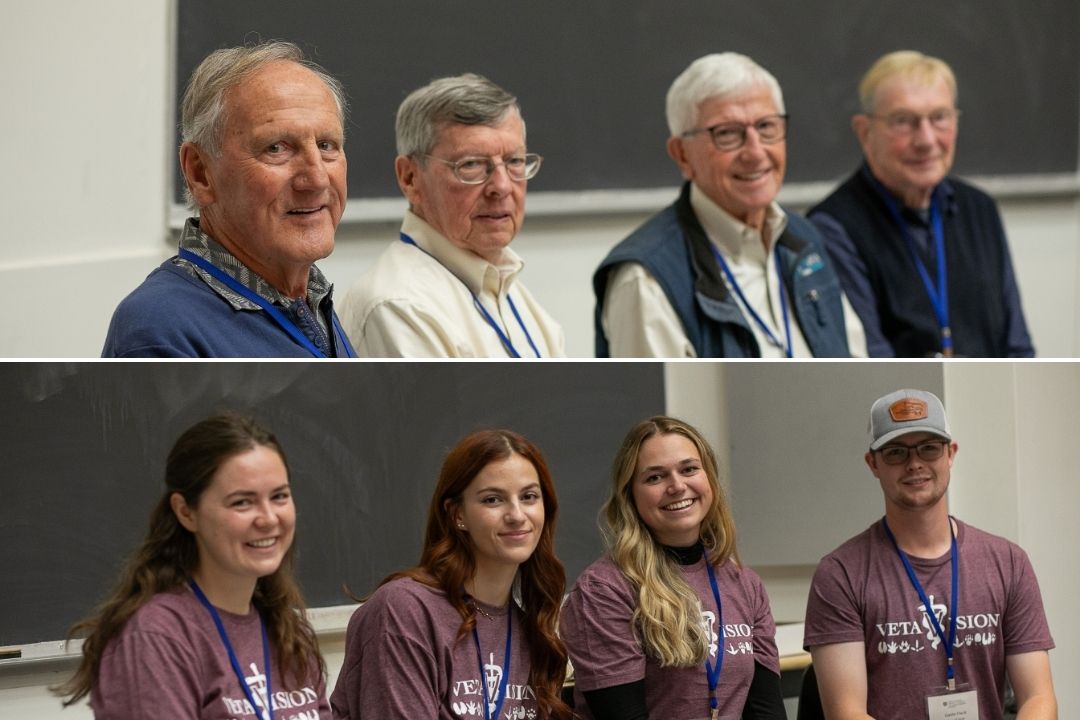

Members of the WCVM’s first graduating class from 55 years ago came together with students from the Class of 2026 to reflect on the evolution of veterinary education and clinical practice over the past 50 years.

Dr. Gillian Muir, the college’s dean and a 1988 WCVM graduate, teamed up with third-year veterinary student Karlynn Dzik to moderate the discussion. Panelists included Drs. Wayne Burwash, Ross Clark, Grant Maxie and Ed Neufeld from the Class of 1969 along with four students from the Class of 2026: Emerson Ferrier, Gavin Fleck, Ellen Marshall and Annie Zehnder.

The following questions and responses give a snapshot of the panel discussion.

Note: questions and responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Q. What does a day in the life of a vet student look like today versus the 1960s?

Gavin Fleck: We're typically scheduled for classes from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., but we get Wednesday afternoons off. Our days consist of lecture hours — anywhere between four to seven hours — and some lab time. Particularly this year (third year), we've been doing a lot more with live animals and doing case discussions in our clinical skills course. It's been a really fun year.

Dr. Ed Neufeld: Well, we weren’t in this room. This room (WCVM lecture theatre) didn’t even exist. We were in the IHU (Interim Housing Unit), which is now [represented by] a little plaque on the wall down the corridor. It was one room with microscopes all around and we really lived and worked in that room.

Dr. Wayne Burwash: It was great for us in that there was no senior class, so right from the start we got to go into clinics. But I look around today and I see the props (tools) that you guys learn from, and I think, “Oh, we could have been a lot smarter if we'd had those!”

Q. How has the profession changed since you became a veterinarian?

Dr. Wayne Burwash: Technology has revolutionized things and so has the explosion of knowledge. There’s a lot of specialization now and it’s hard to keep up. There's also more part-time work. A lot of us worked six to seven days a week when we started practising. Now we see veterinarians working maybe three or four days a week, which is a good change.

Dr. Ed Neufeld: One of the things I see is the growth of specialty and referral practices. And that has been a big boost in the profession — surgical procedures that are difficult and you don't do every day can be referred to somebody who's done a lot of them.

Q. Where would you like to see the profession grow in the future?

Ellen Marshall: I’ve had some experience working with artificial intelligence for charting, and that’s been an interesting change. There are programs now where — as you’re doing a history with a client — it records and creates a document for you. And it's been interesting, especially in really busy practices where it takes some of the administrative workload off of the staff.

Q. What was the diversity of education like at the WCVM in 1969?

Dr. Ross Clark: When we first started I think there were five WCVM faculty members — but the types of species that we dealt with were whatever showed up.

Dr. Grant Maxie: I think we had a very well-rounded education because we did get exposure to everything that came in the door — we basically did everything. When we learned about bovine reproductive rectal palpation procedures, we all went down to Intercontinental Packers and palpated a couple hundred cows at 5 a.m. That's just what we did.

Q. How important are the relationships that you form with your classmates?

Emerson Ferrier: I think that the veterinary community is pretty small. Not just your class — but also your classes before and after you. I feel like we're all going to be connected and we'll all be in each other's lives. It's a pretty tight-knit community out there, and I'm really grateful for that.

Q. How is the shortage of veterinarians affecting the profession?

Annie Zehnder: Speaking to clinicians that I've worked with for a long time, lots of them are trying to retire and they’re struggling to find people to take over, especially in rural locations. Although it's scary to go into a profession where there is a shortage, it puts us in a unique position where we're able to choose where we want to go.

Dr. Ed Neufeld: When we graduated in 1969, we had to work at it a little bit, but we all got jobs. In 2024, you have the choice of any job you wish. The disadvantage is for the people who are recruiting veterinarians. I have colleagues who cannot staff their veterinary hospital any longer and have had to sell the practice, and that’s sad. It's a problem that needs to be addressed and solved.

Q. How important are client communication skills to the veterinary profession?

Dr. Ed Neufeld: During my first three years of practice, I don't think I was a very good veterinarian. I knew all the veterinary skills, but I didn't know people skills. I just wanted to get the diagnostic test done to get the animal out. It wasn't until after my fourth year in practice that I started to figure it out. Veterinary medicine is about more than medicine — it's about working with people.

Dr. Ross Clark: In all my years of practice, I never found a patient that was carrying his own wallet. If we do not communicate well with the one who does carry the wallet, that's going to be a problem for us and we're going to have a lot more failures than successes.

The WCVM is celebrating its 60th anniversary in 2025. Throughout the year, WCVM Today will post stories that highlight the WCVM's history as well as its people, programs and successes.

Visit the WCVM Turns 60 web page for more details about the college's 60th anniversary celebrations.