Canada’s first veterinary social work program celebrates 10 years at the WCVM

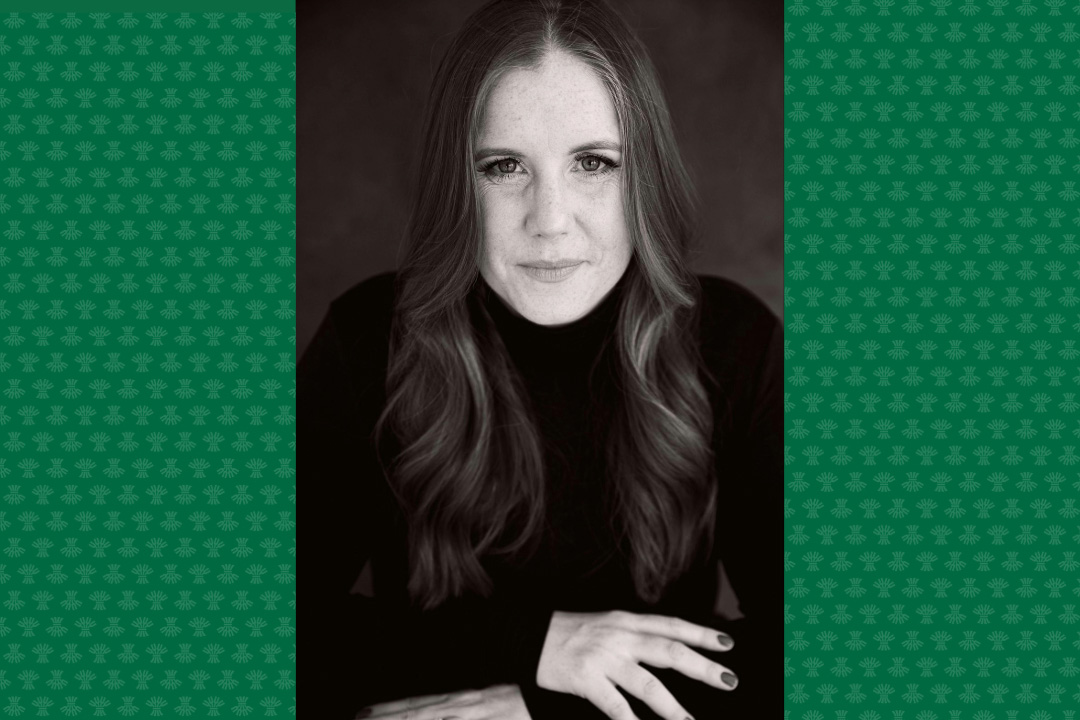

A decade ago, Erin Wasson was completing a Master of Social Work degree program at the University of Regina (U of R) when two of her mentors approached her with the idea of establishing a veterinary social work program at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).

By Tyler SchroederWasson was intrigued with the idea, which was proposed by Dr. Darlene Chalmers (PhD), Wasson’s graduate supervisor and an associate professor in the U of R Faculty of Social Work, along with WCVM professor Dr. Trisha Dowling (DVM), While the field of veterinary social work was virtually unheard of in Canada at the time, the University of Tennessee’s program had been operating since 2002 and its structure served as a successful example of what could be accomplished in the field.

Wasson, Chalmers and Dowling soon gained support from Dr. Judy White (PhD), former dean of the U of R Faculty of Social Work, Dr. Doug Freeman (DVM, PhD), former dean of the WCVM, and Doug Harder, social worker and clinical supervisor with the Saskatchewan Health Authority.

“They were eager to have a social support resource in the college, and I’m really grateful that they put their trust and support behind me to lead it,” says Wasson.

Wasson initially expected to spend four months building a foundation for the program before moving on in her career. But the temporary role became a full-time position once she finished her master’s degree, and in 2015, Wasson became Canada’s first veterinary social worker.

Ten years later, Wasson is a clinical associate and veterinary social worker at the WCVM Veterinary Medical Centre (VMC). In her role, Wasson concentrates on addressing the emotional and mental health needs of animal owners and caregivers.

“Animals hold a special place of unconditional love and acceptance in our lives,” says Wasson. “Whether you’re a veterinarian, a [livestock] producer or a pet owner, there are many tough situations where you may need support. But there’s been a positive shift in our attitudes to seeking help and managing hardships.”

Wasson’s role as leader and the sole member of the WCVM’s veterinary social work program involves training house officers in transferable clinical skills, influencing policy at government and institutional levels, conducting research related to human and animal welfare, and providing clinical support for faculty, staff and hospital clients in a wide-ranging capacity. A major responsibility of her work involves meeting with individuals to address their needs through direct counselling services.

“Often, I’m offering support over grief and loss, but that can cover many different avenues. Clients may have concerns over having to share bad news with their kids or families, or [they] need support in making end-of-life decisions for their pets,” says Wasson. “Other clients could be dealing with the stresses of managing disease outbreaks in livestock and the financial repercussions that result from those crisis situations.”

Wasson is active in advancing community outreach and building partnerships with organizations outside of the college. She has worked with the Animal Protection Services of Saskatchewan on animal welfare investigation cases, and she has provided continuing education resources for the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA) and the Saskatchewan Veterinary Medical Association (SVMA).

Wasson also does referral work for Community Veterinary Outreach (CVO), an organization that’s committed from a One Health perspective to helping vulnerably housed and unhoused people access primary care and resources for their pets. In turn, by offering veterinary care to their clients’ pets, CVO helps connect humans with health and social services that they need.

She looks forward to new opportunities that help to build awareness of veterinary social work and to share insights of the program with others. Over the years, Wasson has been frequently profiled in media stories — including an in-depth interview on YXE Underground, a Saskatoon-based podcast, in 2019.

“Recently we were asked by the Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW) to do an in-service webinar for social workers across Canada about our niche area of the field. It’s great to be recognized and exciting to share our work with a wide audience,” says Wasson.

In October 2017, a large wildfire in southwestern Saskatchewan burned more than 30,000 hectares of farmland and killed 400 head of livestock. At the Government of Saskatchewan’s request, Wasson served as a resource for livestock producers, veterinarians and residents affected by the disaster. That experience eventually led Wasson and Dr. Audry Wieman (DVM) to co-author “Mental health during environmental crisis and mass incident disasters,” a paper published in Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice in 2018.

Their work now serves as a guide for veterinarians, whose role as first responders in times of disaster can extend to providing livestock producers with social support during decision-making related to animal health.

Wasson is proud of the progress and impression that the program has made since its inception, highlighting its value in recognizing the core needs of animal care providers.

“We’re seeing a generational shift in how animal care providers are making adjustments to take better care of themselves. There are great demands in this profession with stressful work environments and resource shortages so prioritizing your well-being and creating a sense of harmony between life and work is so important.”

Wasson says she hopes her program can continue to thrive and serve the changing needs of her clients, and she is encouraged by the enthusiasm shown in the national growth of veterinary social work programs.

“In recent years there’s been a real excitement within the field of social work around what veterinary social work is and how it works. There are now several other veterinary social workers across Canada, which doesn’t sound like many when you consider the number of veterinary practices. But it’s quite a jump from where we originally were when we started out,” she says.

“After doing this for 10 years, people are still reaching out and view me as a safe space for support. I’m so grateful for the tremendous support of WCVM faculty and staff to operate this program with a sense of autonomy and provide the best possible service based on the needs of the community.”

The WCVM is celebrating its 60th anniversary in 2025. Throughout the year, WCVM Today will post stories that highlight the WCVM's history as well as its people, programs and successes.

Visit the WCVM Turns 60 web page for more details about the college's 60th anniversary celebrations.